If you’ve been following this blog for any amount of time, you know that exploring the local art scene is a top priority for me everywhere I go. What muses are enchanting the artists of Honduras, Iceland, Benin, Vietnam and Trinidad and Tobago? What does the art reveal about the national psyche?

I took an art history course in college, and although at the time I was singing its praises, I realize now that its presentation of art was told from a very narrow and limited viewpoint. Every artist we studied was a white, Western European male, who was often long-ago deceased. There is SO much more to art than this.

My top two art-related priorities when visiting Vilnius were the Contemporary Art Centre, to see what young Lithuanian artists had been up to since the fall of the Soviet Union, and the Lithuanian Art Museum, the country’s national gallery and home to the largest collection of Lithuanian Soviet Art(!!). You can imagine my disappointment when I scurried over to each institution only to discover that they were both closed for two weeks as they swapped out pieces of their permanent collections.

Most travel blogs extol the virtues of going with the flow and not breaking down when things don’t go according to plan- two pillars of good travel that I also subscribe to- but it is ok to take a it’s-my-party-and-I’ll-cry-if-I-want-to moment and lament the loss of an experience you were really looking forward to.

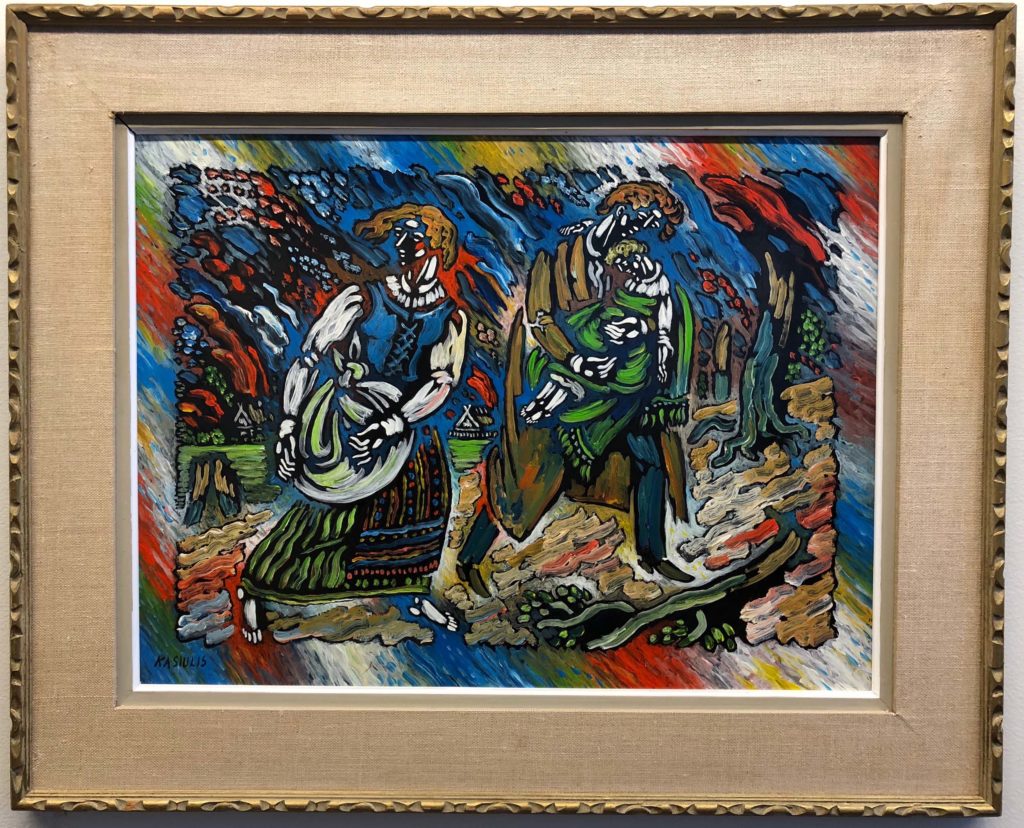

After my 45 seconds of pouting were over, I opened google maps, searched for art museums in Vilnius and hit the jackpot when I was directed to the Vytautas Kasiulis dailės muziejus (art museum). This museum isn’t even mentioned in the Lonely Planet guidebook for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (which testifies to how worthless that once-great series has become) and I would have completely missed out on the exposure to Vytautas Kasiulis had the other two museums been open; all’s well that ends well as the Bard so wisely wrote.

Vytautas Kasiulis dailės muziejus (art museum)

Vytautas Kasiulis was born in 1918, the same year that Lithuania declared its independence from the Russian Empire. He was part of the first generation to grow up both ethnically Lithuanian and with official Lithuanian citizenship. After holding several post-graduate exhibitions in his homeland, he fled Lithuania in the early 1940s, finally landing in Paris in 1948. From his new French home, he lived and worked in exile until Lithuania received its independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

Although Kasiulis achieved great success in Paris, as well Copenhagen, New York and Toronto, his works had been banned by the Soviets and had never publicly been shown in the Lithuanian SSR. Kasiulis passed away in 1995, having at least been able to experience the free state of Lithuania once more, but it wasn’t until 2009 when his widow, Bronė, loaned 150 of her late husband’s paintings to the Lithuanian Art Museum for a special exhibition, that he finally received his due at home.

The exhibition was a great success, extending several times. Bronė struck up a deal: she would donate the entire collection to the state if they created a museum to permanently house and display Kasiulis’ works. City government voted to refurbish the neoclassical Friends of Science building for this purpose and in 2012 the art museum was opened to the public.

Kasiulis mostly painted in bright, vibrant colors. In his earlier years, he drew inspiration from village life in rural Lithuania, but after his move to Paris he created brilliant tableaus of the bustling street scenes in the French capital. Dancers, musicians and artists were frequent subjects of his works. An artist painting a portrait of an artist painting a portrait (often with the use of mirrors) is a recurring theme.

Imagine if I had stuck with Lonely Planet’s Top 10 Vilnius list or had sulked in my hostel room over the closure of my pre-planned museum choices? There are a plethora of resources out there for us travelers to use; don’t rely on just one! Also, when things go wrong don’t cut off your nose to spite your face. After a stomping of the feet and dramatic sigh, move on and make the most of your situation.

Street Art & The Užupio Respublika (Užupis Republic)

Outside of Vilnius’ art museums, the best place to find art in the capital is, well, outside. Street art is everywhere, but the greatest concentration is easily in Užupio/Užupis (Lithuanian/English and both pronunciations are used fairly interchangeably when asking a local for directions to the area). Užupio means on the other side of the river, and that’s exactly where Užupio is- cross the bridge over the Vilnelė River and you’ll find yourself in the unofficial official “Republic” of Užupio.

During Soviet times, Užupio was the poorest area of Vilnius. Starving artists, the homeless and prostitutes occupied the abandoned buildings in post-war Užupio. After Lithuania declared independence in 1990, Užupio became an even greater magnet for artists, calling over 1000 bohemians from across the country to relocate to the district. In 1998, this motley crew declared their own tongue-in-cheek independence from Lithuania. Poet and author of the Užupio Constitution, Romas Lileikis, was elected president. A cabinet was formed; currency was created as was a passport stamp. Užupio Day is celebrated on April Fool’s and you can get your passport stamped by one of the guards when you visit for a small fee.

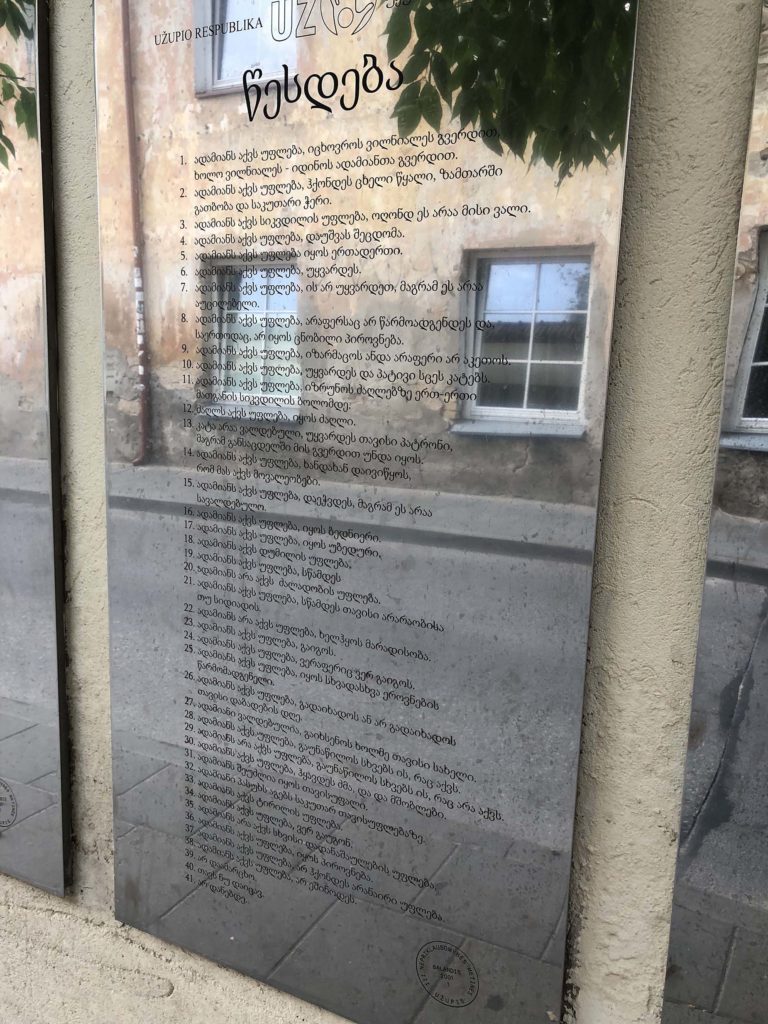

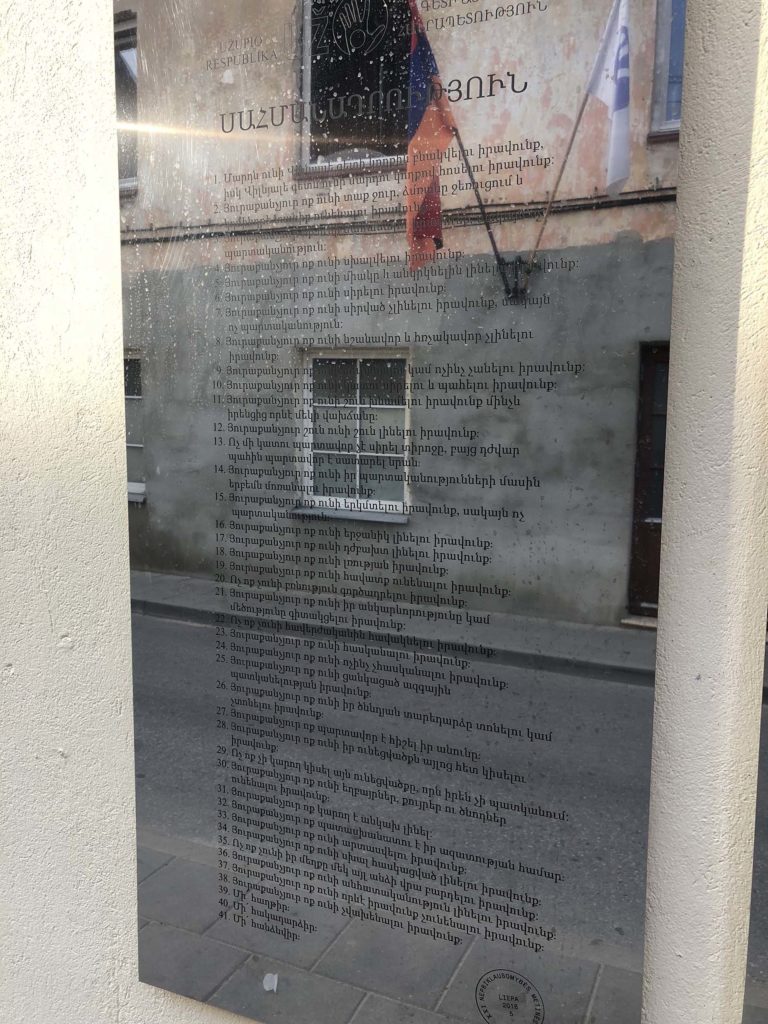

All languages of the world are official languages of the Užupio Respublika. One of the unique places to visit is the Constitution Wall, where the 38 articles and 3 mottos of the republic are posted in various languages. The constitution is a humorous and thought-provoking read and is the best way to comprehend the vibe of the neighborhood.

Here is the constitution in English:

- Everyone has the right to live by the River Vilnelė, and the River Vilnelė has the right to flow by everyone.

- Everyone has the right to hot water, heating in winter and a tiled roof.

- Everyone has the right to die, but this is not an obligation.

- Everyone has the right to make mistakes.

- Everyone has the right to be unique.

- Everyone has the right to love.

- Everyone has the right to not be loved, but not necessarily.

- Everyone has the right to be undistinguished and unknown.

- Everyone has the right to idle.

- Everyone has the right to love and take care of the cat.

- Everyone has the right to look after the dog until one of them dies.

- A dog has the right to be a dog.

- A cat is not obliged to love its owner, but must help in time of need.

- Sometimes everyone has the right to be unaware of their duties.

- Everyone has the right to be in doubt, but this is not an obligation.

- Everyone has the right to be happy.

- Everyone has the right to be unhappy.

- Everyone has the right to be silent.

- Everyone has the right to have faith.

- No one has the right to violence.

- Everyone has the right to appreciate their unimportance.

- No one has the right to have a design on eternity.

- Everyone has the right to understand.

- Everyone has the right to understand nothing.

- Everyone has the right to be of any nationality.

- Everyone has the right to celebrate or not celebrate their birthday.

- Everyone shall remember their name.

- Everyone may share what they possess.

- No one can share what they do not possess.

- Everyone has the right to have brothers, sisters and parents.

- Everyone may be independent.

- Everyone is responsible for their freedom.

- Everyone has the right to cry.

- Everyone has the right to be misunderstood.

- No one has the right to make another person guilty.

- Everyone has the right to be individual.

- Everyone has the right to have no rights.

- Everyone has the right to not be afraid.

The three mottos are: Don’t fight; Don’t Win; Don’t Surrender

Even though Užupio has become a popular destination for tourists, especially among young backpackers, the area hasn’t fallen victim to over commercialization. When the “Republic” was formed, the cabinet banned all kiosks, shopping malls and internet cafes in Užupio. The district maintains its rundown charm and it’s a real treat to walk the maze of streets and come upon random murals and street art.

The Vilnelė River is shallow and easy to wade across. A swing was installed above the river and visitors are encouraged to climb aboard and watch the river roll by, as it has the right to, per the constitution!

The one landmark in Užupio that most locals will tell you to seek out is the Užupio angelas (Angel of Užupis). The sculpture of the Angel Gabriel was erected in 2002 and has become the protector of the Republic. It’s the one piece of classical looking artwork in the area and hence feels more counter-culture than the other counter-culture surrounding it.

Street Art outside of Užupio

There is street art all over Vilnius, so don’t think just because you spent an hour or two in Užupio you won’t find more gems across the capital. Perhaps the most famous street art currently on display is “Make Everything Great Again,” by Lithuanian artist Mindaugas Bonanu. This is a satiric take on the famous mural on the Berlin Wall of Soviet politian Leonid Brezhnev and East German leader Erich Honecker locking lips with the telling title of, “My God, Help Me to Survive this Deadly Love.” This Cold War sentiment has been resurrected in Lithuania with Trump and Putin in their own deadly embrace.

From Kasiulis painting in exile to the street art of Užupio and beyond, there is a undercurrent of rebellion in Lithuanian art. Lithuanians pride themselves on being the first SSR to declare independence from the Soviet Union and that fighting spirit is evidenced throughout their culture. They are friendly and welcoming, but also defiant and proud of their heritage. Art has allowed repressed groups to speak for centuries, even when their actual voices have been silenced. This is what makes art in all its form so scary for authoritarian governments. When you visit Vilnius, make sure to take some time to soak up the homegrown artwork: your Lithuanian experience won’t be complete without it.