Soviet history is a fascinating beast. It is filled with brutal horrors, stringent rules and restricted personal freedoms, all the while being layered with comically absurd levels of bureaucracy and amusing ways average citizens managed to get by. Humor was a great defense mechanism and essential for survival. In this post, I will outline the basic events of the two Soviet occupations of Lithuania and point you to where you can go in Vilnius to learn more about this 50+ year period of Lithuanian history.

Act One: Terror and Oppression

Okupacijų ir laisvės kovų muziejus (Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights)

In just the short time since I visited Vilnius, the Genocido aukų muzijus (Museum of Genocide Victims) has already changed its name to Okupacijų ir laisvės kovų muziejus (Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights). Outdated guidebooks (and google maps), please take note!

Founded in 1992, a mere two years after Lithuania declared their independence from the Soviet Union, establishing the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights was obviously a high priority for the Lithuanian people. After one has been forced to bury truths for so long, when that person finally tastes freedom for the first time in decades, the lies quickly dissolve and the real narrative emerges.

But let’s back up a bit. It’s 1918. Lenin and his pals are leading the Russian revolution and the empire is weaker than it’s been in a long time. Seizing upon this golden opportunity, Lithuania and its Baltic sisters (along with the likes of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia) decide to declare independence and make a go of it as fully-realized nations.

Sadly, this didn’t mark a period of smooth-sailing for the nascent Lithuanian government. They continued to fight wars with the newly-formed Soviet Union to the East and Poland to the West, the latter of which still laid claim to Lithuania as it had been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth for so many centuries. After Nazi Germany captured Poland in 1939, the fate of the Baltic Nations was sealed. The Soviets moved 20,000 troops into Lithuania under the guise of helping the nation defend themselves against Germany, and by 1940 the brief, first Soviet Occupation had begun.

During the first Soviet Occupation, this building was used by the organization that would one day be known as the KGB. Any Lithuanian who spoke out against their new oppressors was brought here, interrogated, beaten, tortured and executed. Family and friends of a dissenter suffered the same fate. 15-20 people would be held in each cell, the lights would never be turned off and prisoners were given a single bucket to use a communal toilet.

By 1941, the Nazi Army had wrested control of Lithuania from the Soviets and had begun implementing their own unique form of warfare against the Lithuanian people. (I want to give the Nazi Occupation its own post, but the long and short of it is 240,000 people were killed by the Nazis between 1941-44, including 200,000 Lithuanian Jews.) The Gestapo moved right in and picked up where the Soviets left off. In 1944, as Germany‘s stranglehold over Europe weakened, the Soviets “liberated” Lithuania and the second occupation, which would last 45 years, began.

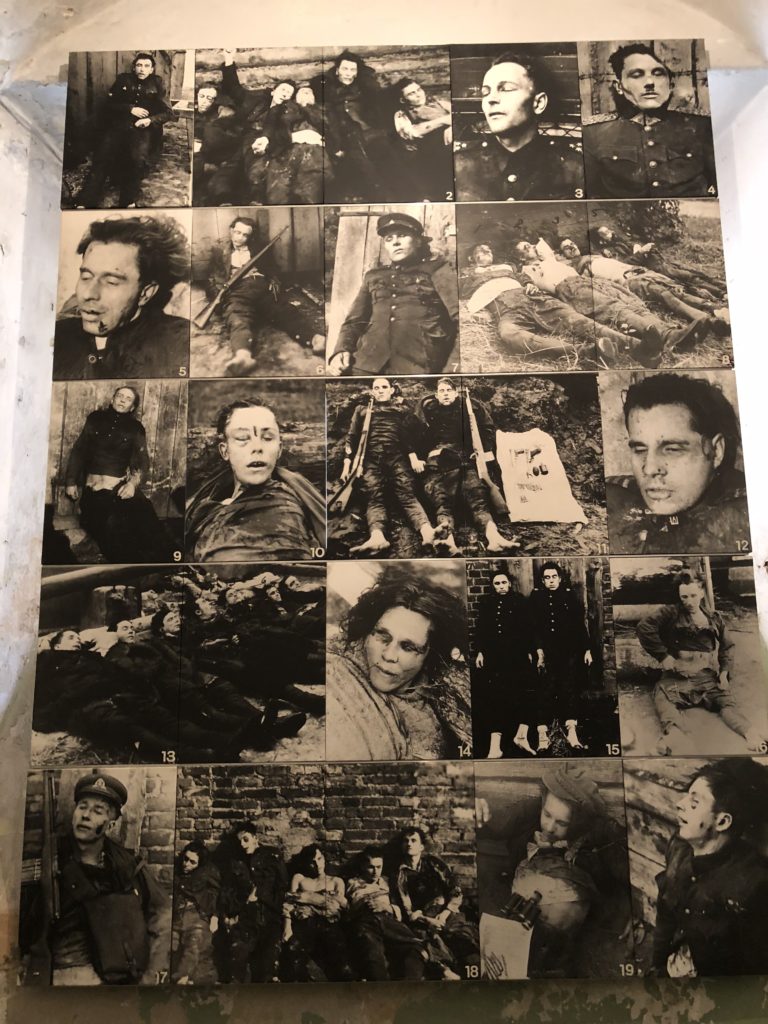

As the expanded, post-war Soviet Union took shape, a puppet government was installed into the newly-minted Lithuanian SSR with a simple edict from Stalin: assimilate or die. Between 1944 and Stalin’s death in 1953, 20,000 Lithuanians were killed by the KGB. Instead of hiding these deaths, the bodies were often laid out in town squares and markets around the country to act as a deterrent against other acts of Lithuanian nationalism.

If the authorities determined that your crimes weren’t capital offenses, you and your family would be shipped off to the gulags- often a death sentence in its own right. If you survived the actual deportation, the hard labor with minimal rest and nourishment would eventually spell your doom. After Stalin’s death, the gulags were closed and people were gradually allowed to return to their home cities, although many found there was no home to return to.

The raw statistics during the second occupation are staggering. Between 1944-90, 200,000 Lithuanians were arrested and imprisoned by the KGB. 25,000 of those arrested died in prison. 132,000 Lithuanians were deported, 28,000 of whom died in the Siberian gulags.

The museum is obviously a difficult place to visit and not to be paired with a frivolous activity. No matter how much you think you know about the Holocaust, Soviet gulags, Cambodian Killing Fields or the Rwandan genocide, you can’t prepare yourself for how difficult it will be to be confronted with these eye-opening museums and memorial centers associated with such human violence.

Act Two: Architecture and Daily Life

Remember Stalin’s ultimatum: assimilate or die? Well, what became of the people who did assimilate, or at least kept their mouths shut in public about the communist regime? What was local culture and daily life in Soviet Lithuania like? To answer these questions, we first should examine how the Soviet Union functioned culturally, both in theory and practice.

When discussing Soviet times with my dad, I’ve noticed that he uses “Russian” and “Soviet” interchangeably, as if they are synonyms. He’s both right and wrong; as much as the Soviet leadership in Moscow might protest, the line between Soviet and Russian is very muddled. (Ah, the paradoxes of Soviet life!)

When the Soviet Union was founded in 1922, Russia officially ceased to exist. The Russian language and culture obviously lived on, but as a nationality and an internationally recognized form of citizenship, all former Russians had technically morphed into Soviets. (The same is true of Azerbaijanis, Georgians and Armenians who were folded into the Soviet Union in 1921, although most of them would scoff at ever being labeled “culturally Soviet.”)

By 1944, the Soviet Union now was firmly in control of the Baltic States, the Caucuses, the five Stans and Moldova; Russia, Belarus and Ukraine were the three founding members of this powerful alliance. By this point, the Soviet Union was comprised of literally hundreds of various ethnic groups, each with their own languages and cultures. In theory, the plan was not to eradicate culture completely, but to homogenize it into a monolith. The goal was to bring all of these people together- by physical force, if necessary- and have them awaken from their cocoons fully-formed Soviet butterflies. (But, let’s face it, we’re taking about the Soviets here. It was definitely a moth and not a butterfly.)

The reality was, of course, much different. Very few people willingly want to give up their language and culture, and even if they did, the Soviet leaders were disingenuous (at best) about creating this one, new Soviet culture. It’s not like they invented a new Soviet language and then took the best of every culture’s opera, ballet, literature, poetry and dance and mashed it all up to create a multi-ethnic new Soviet culture. The reality is the official language was Russian, which eventually was forced upon every citizen in schools and all official government agencies, and the culture was essentially Russian, with slight modifications in the various SSRs.

The one area that truly may have been a unifying force was architecture. Soviet brutalist architecture could be found in every SSR as cities grew and were reconfigured in the regime’s preferred style, often doling out assignments to local architects who would maintain this new Soviet aesthetic with nationalistic tweaks. Because these buildings are such stark reminders of the Soviet era, many have been destroyed or condemned to a life of decay. They sit boarded up and graffitied- artifacts from another time.

Vilnius With Locals

I’m usually one to bristle at the suggestion of taking a tour, but I’ve learned that while a bus tour full of headphone-wearing, led-around-by-an-umbrella-wielding-guide people may not be for me, there are many smaller, local tours that are actually fun, informative and worthwhile. Vilnius with Locals is great small-group tour company that provides student-led themed tours around the capital. They offer a Soviet tour, Jewish tour, Alternative tour (graffiti and street art), food tour and late night ghost tour. Naturally, I signed up for the Soviet tour (10 euros; 2.5 hours), but after enjoying it so much, I would gladly have taken the Jewish and Alternative tours if I had more time.

Sporto rūmai (Palace of Concerts and Sports)

The Sporto rūmai (Palace of Concerts and Sports) is hands down the coolest building in Vilnius. It’s a gigantic beast that looks like the Titanic ramming into the iceberg that sunk it. The Palace (you have to love the irony of the Soviets, who were against all bourgeois and capitalist symbols, naming every institution, “The Palace of ______) was built in 1971 on the site of the oldest Jewish cemetery in Vilnius. A plaque commemorates the destruction and describes how the Soviets carted unearthed bones off to the landfill while the bodies that remained are now sitting under feet of concrete.

The Palace of Concerts and Sports once held 4,408 seats and remained in use until 2004 when it was deemed unsafe to enter. There are plans to renovate the building and turn it into a convention center, but there have been protests from the Jewish community who demand the land be returned to them and the cemetery restored.

Lietuvos Nacionalinis operos ir baleto teatras (Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre)

The National Opera and Ballet companies were founded in 1920, but it wasn’t until 1974 that the Soviets built this new “Opera Palace” for them to take up residency. In Soviet Brutalism, all building materials are revealed to the viewer; concrete, bricks and steel are left exposed. The emphasis was supposed to be on function over aesthetics, although the aesthetics certainly weren’t ignored! Another characteristic you can see in the opera house is the large glass panels. The government touted complete transparency between the public and these public institutions- which of course was total bullshit- but the Soviet Union, like most authoritarian regimes, thrived on propaganda and empty symbolism.

Žalias tiltas (Green Bridge)

The Green Bridge isn’t actually a Soviet creation, but it’s included on the tour because it illustrates how the Soviets transformed local symbols by putting their own stamp on them, so to speak. The Green Bridge is the oldest bridge in Vilnius, connecting the old and new towns on either side of the Neris River. The bridge has always been a heavily-trafficked meeting spot; the Soviets searched for maximum impact areas where the greatest number of residents could receive their daily reminder of their new “values.”

On each of the bridge’s four pillars were placed statues symbolizing four Soviet ideals: Agriculture, Youth Education, Industry & Construction and Guarding Peace. The statues depicted happy, smiling Lithuanians hard at work, with hand over heart for the Soviet flag. After independence in 1990, there was a large push to remove the statues and place them in a museum; finally, in 2016 they were knocked off their pedestal.

Lietuvos nacionalinis dramos teatras (Lithuanian National Drama Theatre)

The National Drama Theatre has occupied its home since 1951, but the building’s most recognizable feature, the Feast of Muses, wasn’t added until 1981. While still under Soviet authority, the 1980s saw great changes within the Lithuanian artistic communities as controls were relaxed and once-forbidden elements crept back into sculptures and paintings. This depiction of the Greek muses of Drama, Comedy and Tragedy are still quintessentially Soviet though. Notice how Comedy barely cracks a smile; they look a lot more like the witches from Macbeth than the ensemble of Hello, Dolly!

Lazdynai

A visit to Lazdynai, an outer suburb of Vilnius, was not included on the walking tour, but I visited the area the following day after learning about the district from the guide. As Vilnius’ population ballooned in the 1960s and 1970s, more housing (which was all government-owned) was desperately needed.

Lazdynai was created to house 32,000 residents in Soviet-style block apartment buildings. The city planners had grown weary of the soulless apartment complexes built across the USSR and, after a careful study of Finnish design, decided to incorporate trees and green spaces around the buildings. At first this raised the suspicions of the big wigs in Moscow, but the project was allowed to continue and the architects ended up winning the Lenin Prize that year, the greatest Soviet honor for architecture. (I took these photos of Lazdynai from the Vilniaus TV bokštas [Vilnius TV Tower], which I will discuss below.)

Šiuolaikinio meno centras (Contemporary Art Centre)

This one hurts a little. One of the places I was most excited to visit in Vilnius was the Šiuolaikinio meno centras (Contemporary Art Centre). Unfortunately, it was closed for two weeks during my visit to change over all the exhibits. I was pretty heartbroken, but what could I do except start planning a return visit…

The building itself was erected in 1967 and originally was called the Dailės parodų rūmai (Art Exhibition Palace). After independence, a new wave of young artists went crazy without any of the Soviet constraints and in 1992 the Contemporary Art Centre was born to display their works.

Daily Life

One of the perks of the Vilnius with Locals tour was hearing the anecdotes about what daily life was like in Soviet times. My guide was born post-independence, but his parents were born and raised in the Lithuanian SSR and that was the only life they knew until 1990.

In theory, everything was provided for you by the government, but in practice nothings was ever available. If you needed a new washing machine or stove or refrigerator you put your name on a list and when it was your turn, you were given a new appliance. Of course, you might have to wait months, if not years, for certain items and when it was your turn you received the next stove off the assembly line. You didn’t get a choice of color, design, special features- it was take it or leave. Private property didn’t exist; the agreement was that you worked and then the state would provide all your basic needs.

Because of this, there was a booming black market as people craved fresh fruit, speciality foods and home goods that they couldn’t receive from the government. The guide told us how his mother had never tasted a banana or an orange before 1990 and viewed them as such rare and exotic fruits.

Satirical magazines were oddly allowed to remain open, but their satirical targets were supposed to stay firmly pointed at the West and capitalism. In reality, the editors found subversive ways to criticize the communist regime through humor and cartoons.

Travel outside the Soviet Union was rarely allowed and visitors to Vilnius were only allowed to stay at one hotel and could not leave the hotel unless escorted by a Soviet tour guide. All TV channels, radio stations and newspapers were state run and were often filled with lies: the original fake news.

I ended up chatting with the guide for an extra 45 minutes after the tour ended about how young people view the Soviet period and its currently role as a scare tactic/talking point in modern Lithuanian politics.

Act Three: Resistance and Rebirth

Lithuania was the first SSR to declare independence from the Soviet Union on March 11, 1990. (Trivia fact: Kazakhstan was the last SSR to break away from the Soviet Union when they declared independence on October 25, 1990.) The Soviet Union didn’t fall like the Berlin Wall; its death was drawn out and produced much suffering as the ex-superpower fractured.

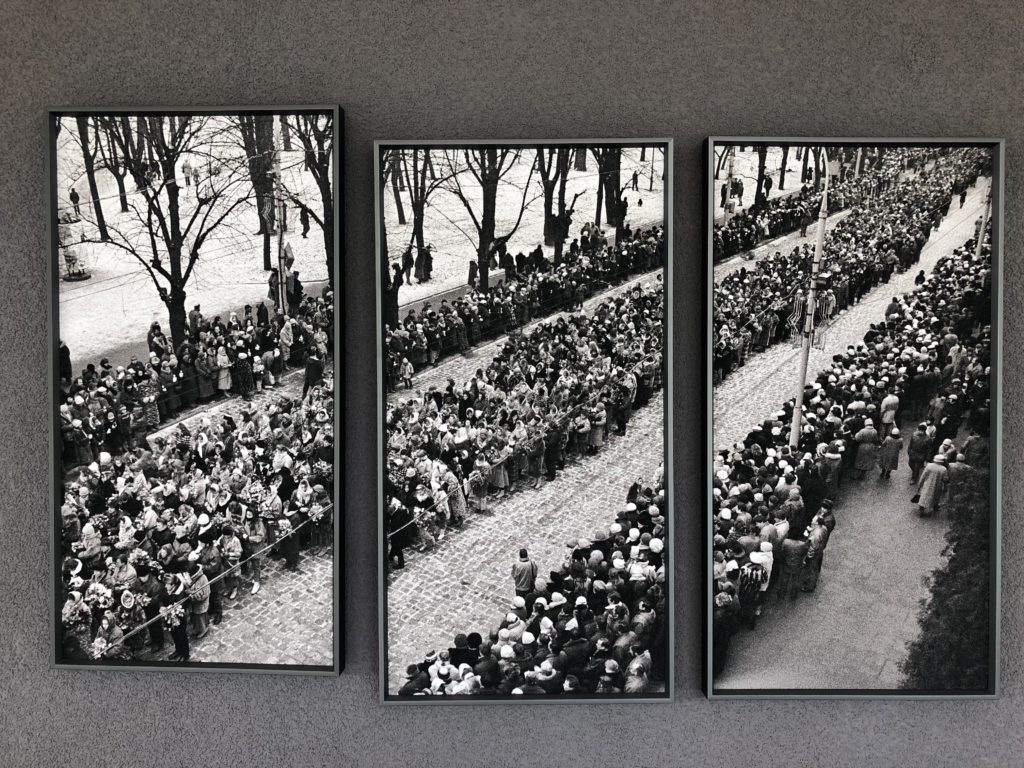

As coups brewed in Moscow, rallies calling for peaceful transitions of power sprung up across the Baltic States. On August 23, 1989 a human chain of two million people known as The Baltic Way stretched from Tallinn to Rīga and ended in Vilnius. Lithuania’s declaration of independence caused a domino effect across the country. The Soviets Army finally moved to quash these rebellions and in January 1991 they began capturing various buildings and institutions in Vilnius. At 2:00am on January 13, the Soviets brought tanks and heavy artillery to the TV Tower, which was broadcasting that Lithuania was a free nation. The army killed thirteen Lithuanians defending the Tower (with a fourteenth succumbing to wounds the following day).

The Soviets may have succeeded in shutting down the TV Tower’s broadcast, but winning the battle cost them the war. The fourteen victims became instant martyrs and their funerals were attended by every Lithuanian. The Soviet Union could not fight a war on sixteen fronts, not to mention deal with the myriad of internal Russian struggles. Vilnius was liberated as the Soviet Army slunk away. Lithuania eventually becoming an official member of the UN, and later the EU.

Construction on the TV Tower began in 1974 and it is still broadcasting today. A museum about the events of January 13, 1991 has been installed in the base of the tower and you can travel by elevator 165m (541 ft) to a viewing platform and revolving restaurant. When I told one of the hostel workers I would be visiting the TV Tower she warned me that the restaurant was “overpriced and disgusting,” so fair warning about that. The views from the tower allow you to see just how green much of Vilnius is, although you wouldn’t know it if you don’t step out of Old Town.

As you can see above, the TV Tower is not within walking distance so you’ll need to take a city trolleybus to get there. Most riders have a monthly public transportation pass, but you can purchase a one-way ticket directly from the trolleybus driver for a Euro. (Don’t expect them to carry much change; large bills will not be accepted.) Line 9 will take you right across from the TV Tower from the new city in about 30 minutes.

Epilogue: Vilnius Today

Modern Vilnius is often separated between the UNESCO-protected Old Town and the modern New City full of malls and commercial high rises, but like bad acne scars, the remnants of the Soviet era can be found speckled across the cityscape and shouldn’t be ignored. Even if you’re not as obsessed with brutalist architecture as I am, it’s worth checking out some of these sights that you won’t find in Lonely Planet. Still, the younger generation has moved on and Lithuania’s admission to the EU has pulled it further from its Soviet past faster than anyone could have imagined.