Oh Guyana, Where Art Thou?

It was my maiden voyage to South America, and naturally I would be going to Guyana. Of the twelve countries that comprise the continent, Guyana is the least visited; according to the latest pre-pandemic stats, 2018 only saw roughly 200,000 travelers venturing into the nation. Considering how much I ultimately enjoyed my time in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital city, I was left pondering why so few make the trek down here, whereas other South American destinations, such are Peru, Argentina and Brazil, remain perennial epicenters of tourism.

The first reason, and I’m loathe to even type these words, is that anecdotal evidence shows many people believe Guyana is in…Africa. (Face palm) Guinea-Conakry, Guinea-Bissau and Equatorial Guinea are all countries in Africa, and yes, Guyana was once known as British Guiana, but Guyana is on the northern coast of South America, bordering Venezuela, Brazil and Suriname. While the Guyanese will cringe and laugh when they hear of people mistaking their country for one in West Africa, they will be quick to correct you about being a South American nation as well. On a geographic technicality, Guyana may be in South America, but the Guyanese identify culturally as a country in the Caribbean. Hence, there is this disconnect with how Guyana is promoted to tourists: the land is covered with dense rainforests that most travelers associate with South America, but the government has opted to partner with Caribbean tourist boards, who normally are promoting an image of sun and sand at the all-evil all-inclusive. These multiple personalities could leave potential visitors scratching their heads.

Guyana, meaning the land of many waters, is one of the least densely populated countries in the world. Georgetown is far and away the largest city; essentially the entire southern 3/4 of the country is unspoiled, jaguar-filled rainforest, still inhabited by nine indigenous tribes who (miraculously) survived European colonization. Guyana is also the only South American nation that has English as an official language, although most people converse in Guyanese Creole on a day-to-day basis. With waterfalls, rainforests, a veritable jungle full of wild animals, plus having English as a commonly spoken language, you would think this would attract a few more tourists than it does. What does Lonely Planet have to say about Guyana?

Funny you should ask about Lonely Planet. They have full-length travel guidebooks devoted to Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Chile- all the usual suspects- but if you want info on Guyana you’ll have to purchase “South America On a Shoestring,” a 1084-page tome that covers all twelve countries in South America. Ok, well out of 1084 pages, how many are earmarked for Guyana? Twenty pages. Yes twenty whole pages, or 1.8% of the guidebook, handles the Guyanese homeland and only two measly, lousy, little pages are allotted for Georgetown. No wonder Guyana remains so far under the radar when the so-called leader of the travel industry either doesn’t know how or is unwilling to promote this special place.

Enter Compton Davis

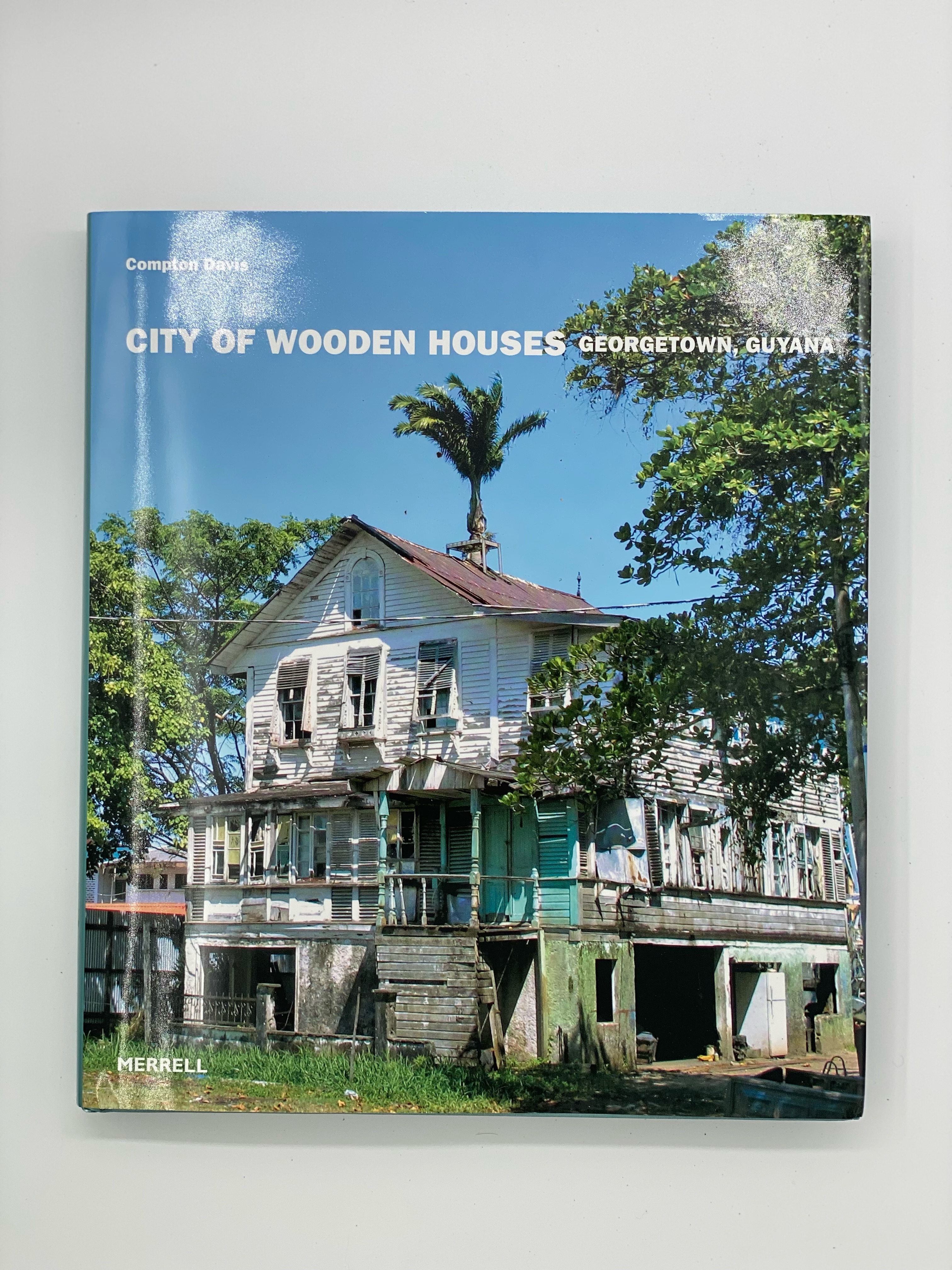

What do you do when guidebooks let you down and resources on the internet are severely lacking? Sometimes you have to come up with a creative workaround, which is what I did when I discovered Compton Davis’ fantastic book, “City of Wooden Houses.” Davis is not a travel writer and his book will not come up in amazon searches for Guyana travel, although it really should. Compton Davis was born and raised in Guyana before completing his education in London. He is not only an architect, but he has also become the leading chronicler and scholar of Georgetown’s architectural past. Despite Guyana’s humid, tropical climate, the British, who held colonial control of the territory until 1966, decided to construct most of their 19th-Century buildings out of wood instead of stone, brick or metal. These wooden buildings, many of which have fallen into a state of disrepair, are the capital’s defining feature and will provide any visitor with days of sights to explore.

After an introductory brief history of Georgetown, Davis divides the capital into five neighborhoods (Queenstown, Kingston, Cummingsburg, Stabroek and Robbstown & Bourda), after which he proceeds to provide pictorial evidence and descriptions of the architectural highlights in each district. His primary goal is to catalogue and preserve the legacy of these structures, but a by-product of his approach is that he has mapped out five perfect walking tours for any visitor to use as a blueprint to navigate his hometown.

Rather than starting my traveling planning with a destination (Guyana/Georgetown), I had to pivot and use an interest (architecture) as a jumping-off point. When the travel industry disappoints, don’t be discouraged. Find a book about an artist or musician or cuisine and then go from there. It might seem like a roundabout way to research a travel destination, but by selecting something you’re already keen on, you’re instantly tailoring your visit to your interests.

Georgetown Quick Facts

Compton Davis steered me in the right direction, therefore I will follow his lead by giving you a little rundown of Georgetown’s past before taking you on a can’t-miss-it tour of Georgetown’s wooden colonial buildings. (Don’t worry: I’ll take a deeper look into Guyana’s history in a later post!)

Georgetown has two official nicknames: The Garden City of the Caribbean and The Venice of the West Indies. In reality, Georgetown is a city that shouldn’t exist. Built in the center of the Demerara River Basin, at high tide, the city sits 1m(3ft) below sea level, somehow kept afloat by a series of canals and an outer retaining wall that keeps the Atlantic Ocean at bay.

The Netherlands was the first European power to colonize Guyana; France, Spain and Great Britain would all take their turns during the several centuries of colonial rule the native people were forced to abide. The Dutch constructed the first seawall along the mouth of the Demerara River in the 17th Century, all the while erecting houses on stilts across the marshy terrain. As their settlement grew, this method of city planning proved to be rather impractical, causing the Dutch to rethink their strategy. Naturally, the Dutch took inspiration from Amsterdam, coincidentally nicknamed The Venice of the North, and employed a similar strategy to Georgetown’s development. By digging a series of canals and trenches, the Dutch were able to drain the delta and reclaim the soggy land that stretched to the sea.

The Dutch named their capital Stabroek, a moniker you will still find in use throughout the city. Stabroek was susceptible to flooding from two directions: the swells of the Atlantic Ocean bursting through portions of the seawall to the north and the mighty Demerara River flooding and overflowing the canals from the south. Alterations and recalibrations were the name of the game as Mother Nature attempted to retake what was stolen from her.

The British established permanent control of Stabroek in 1814, and their first order of business was to rename the capital Georgetown after the British monarch at the time. The colony was christened British Guiana, a title it would retain until Guyana received independence in 1966. Originally, Stabroek was mostly made up of various sugar plantations which fused together in a grid-like fashion to create the city’s layout. The plots of land had to be generously spaced out to accommodate the canals, thus affording each house a large parcels of land, surrounded by trees and splendid gardens, which explains Georgetown’s “Garden City” sobriquet.

As Georgetown has morphed and grown over the years, some canals were filled in with soil, on top of which paved walking paths were installed, creating scenic strolling areas down the capital’s main boulevards. The city’s grid-shaped design coupled with the copious pedestrian pathways allows Georgetown to be extremely friendly to the tourist who wishes to explore on foot. Although mini buses traverse the city, the only time I had to take public transportation was to and from the airport. The only real danger is getting caught in a sudden downpour; I had to purchase an umbrella within the first hour of being in the city.

With the abolishment of slavery by the British in the 1830s, the colonial government attempted to replicate the success they had in Port of Spain with bringing in Indian and Chinese indentured servants to work the plantations. The freed slaves and new Asian workers created a great need for more housing and Georgetown’s building boom was in full swing. It was in these decades leading up to the 20th Century that the bulk of the wooden structures in the capital were built.

Like the Gingerbread-Style architecture that you can find in Port of Spain, Georgetown’s unique colonial wooden architecture is amalgamation of Dutch, French, Spanish, British, African, Indian and indigenous influences. Most of the structures are at least two stories tall, with a bottom level of enclosed stilts used for storage (or nowadays to park cars). Greenheart wood is native to Guyana and is extremely hard and durable. It was used whenever possible, especially for government buildings and the homes of wealthier families.

Louvre windows, jalousies, verandas and porticos are some of the features found in this Colonial-Subtropical architecture. All of these elements served specific functions for the homeowner. Verandas usually wrapped around the entire home and provided a meeting place for acquaintances or unexpected guests. Today, many of these verandas have been walled in and absorbed into the house. Initially, the main two-story structure only contained living spaces: bedrooms, parlors, studies and a dining area. It was too risky to light a fire in these wooden homes, which caused kitchens to be placed in a separate structure behind the house. Along a walkway towards the kitchen, one would usually find a bathroom/outhouse. (It was not until 1889 that the first 650 houses in Georgetown received electricity, with the installation of street lamps following in 1891. It took until 1922 for them to figure out how to install a sewage system in the below-sea-level capital.)

Louvre windows and jalousies are all about ventilation, ventilation, ventilation. These decorative slats allowed for cross breezes to flow through the homes, but they also permitted all manner of insects and critters to enter as well. Today, screens or glass have been placed behind the jalousies, maintaining the aesthetic, but allowing for modern conveniences such as air conditioning to be added to the homes. Greenheart was too dense to be used for fretwork as it would wear down or break the tools of the woodworkers. Each construction company had their own unique fretwork patterns; you could walk around town and just by looking at the fretwork know which carpenters built each structure.

One of the more unique features to Georgetown’s colonial architecture is the “Captain’s Towers of Kingston.” These were actually an Italian influence that placed an off-center tower against the side of a home. Verandas were not built on these so-called “Tower Houses.” The tower was completely functional, with a staircase that connected the rooms couched inside that led up to a viewing platform on the top floor. The ground-floor tower room usually was made into a study, with guest bedrooms above it. As the name would suggest, the largest concentration of these towers can be found in the Kingston neighborhood.

Two forces have been working against Georgetown’s wooden buildings ever since their inception: fire and the weather. Safety regulations of the 19th Century are obviously not what they are today and large swaths of the capital went up in flames during those early years, having to rebuilt time and again. As advancements in fire prevention have aided keeping the buildings safer in the present day, the humid, tropical weather has become the number one enemy of Georgetown’s heritage. Native greenheart wood is hale and hearty, but cheap pine was also imported from the United States and Canada to cut costs, a folly that has led to rotted and warped wood; some buildings are starting to look a little more like the Leaning Tower of Pisa as floorboards sag and support beams give in to their age. Multi-million dollar restorations are the only hope of saving these buildings. A few have been deemed too far gone and have subsequently been torn down, but 13 of the most important structures, including St. George’s Cathedral, the State House, Stabroek Market and St. Andrew’s Kirk, have been placed on a tentative UNESCO list. If elevated to official UNESCO status, the government would receive funds to help repair and maintain these architectural wonders for generations to come.

St. George’s Cathedral

Difficult to capture in a single photo, St. George’s Cathedral is the 2nd-tallest wooden religious structure in the world. Other than the stained glass windows, this Anglican cathedral is 100% made from wood. Shockingly, no brick, stone, concrete or metal was used to construct this massive structure. St. George’s tower is 43.5m (143ft) tall and was modeled in the Gothic-Style with some subtropical twists.

(Just to give you an idea of how quickly a storm can come in and go in Georgetown, I took the first photo upon entering the cathedral and this second photo as I was exiting. It rains a lot in Guyana, but it’s usually not a sustained, all-day deluge. You’ll get an intense 5-10 minute downpour and then the clouds will part and the sun will quickly reappear.)

Construction began on St. George’s in 1892 with an official opening in 1899, but this wasn’t the first church built on this spot. The original building was poorly designed and eventually cracked and broke in two. To avoid a similar fate, architects whipped up a traditional stone Gothic-Style cathedral, but the building materials were later deemed too heavy when it was clear that they would cause the cathedral to sink into the marshy soil. The designers relented and refashioned St. George’s into a wooden structure, but with the mandate that it only be built with local materials, preferably from greenheart trees. This has largely allowed the cathedral to remain rot and insect-free for most of the 130+ years it has been in use.

The cathedral’s purple and yellow stained glass windows may be iconic in the city, but stained glass was not reserved solely for places of worship. Homeowners installed solid-color stained glass to help diffuse the sunlight and reduce the heat on the upper floors of their living spaces. The Gothic design permits a large amount of natural light to enter the apse, but the way it is transformed when passing through the colored glass causes the interior to have a surrealistic, otherworldly glow.

St. George’s is full of Gothic elements that have been adapted to suit Guyana’s climate. You still have the arches, flying buttresses, hammerbeam roof and decorative pillars in the sanctuary, but here they have been molded from greenheart wood modified to withstand the humidity. The white walls have a faux-Tudor black trim that further evokes the nation’s former colonial master. The chandelier was a gift from Queen Victoria on the occasion of her jubilee.

If you’re only in the capital for a few hours and have limited time to see one building, this is probably the one you’ll visit. St. George’s Cathedral is on the Guyanese $100 bill, postage stamps, postcards, t-shirts in the market place, billboards to and from the airport- the government views this as not only one of the great symbols Georgetown, but as the country as a whole. No trip to Guyana is complete without paying St. George’s a visit.

City Hall

Georgetown was officially incorporated in 1837 and the newly-elected mayor (and when I saw “elected,” I mean appointed by the British government) needed a place from which to govern. Committee after committee was formed and as is so often the case with local politics, it took decades to get anything done. It wasn’t until 1887 that a design was agreed upon and ground could be broken on what is now City Hall.

Like St. George’s Cathedral, local timber was used except for the tile roof and iron columns. The centerpiece is obviously the 23m (75ft)-tall tower that dominates the front-facing facade. The top of the tower is adorned with four conical spheres and the interior (not open to the public) contains mahogany staircases. When this Gothic Revival structure was opened in 1889, the capital’s residents lined up for hours to tour the building and admire the craftsmanship. Today, City Hall has seen better days. Fundraising efforts are underway to replace damaged pieces of wood and restablize the tower.

National Library (Formerly Carnegie Free Library)

In 1909, Andrew Carnegie of the wealthy New York Carnegie clan, donated £7000 to a fund that would help build libraries across the Caribbean. Mr. Carnegie, naturally, named the libraries after himself, but post-independence, the government simply changed its name to the National Library. It initially was a closed system that allowed no public access to the books. You had to submit a request and then your selection was brought out to your table. This was eventually dismantled, allowing people to freely browse the stacks, whether you’re a library member or not. The best part about the library today? They have free WiFi and if your phone dies, there are free computers that non-members can use as well. Libraries might not be the most exciting entry on your must-see-tourist-hot-spots list, but it’s always handy to know where they are. I’ve found that if you’re lost or need assistance, turning to a librarian for help will never steer you wrong!

High Court (Victoria Law Courts)

Built between 1881-1887, the High Court (formerly the Victoria Law Courts) is one of the most striking wooden buildings in town. The local government could not decide between two competing design proposals, so they gave the first floor to one architect and the second floor to the other architect. (I really couldn’t make this stuff up if I tried!) The ground floor employs some masonry and iron to create a Greek & Roman-inspired Classical Style. The upper floor is all timber in a Tudor Style. The roofs are high-pitched and topped with metal ornamental cresting.

A statue of Queen Victoria was placed in front of the court and grew to be one of the most hated symbols by the Guyanese in the capital. During the first half of the 20th Century, as the calls for independence began to grow, this image began to embody everything that was hated about colonial rule. In 1954, dynamite was strapped to the statue and detonated, blowing off Victoria’s head and one of her arms. The head was reattached, but the arm was damaged beyond repair. After independence was achieved in 1966, the statue was moved to the Botanical Gardens, but it was vandalized time and time again. It was later moved back to the High Court, but as recently as 2018 it was covered with red paint and is still grumbled about by passers by.

Stabroek Market

Ok, not a wooden building, but along with St. George’s Cathedral, Stabroek Market is the most important building and meeting spot in the city. A market has existed on this spot since 1792, when the Dutch allowed their African slaves to trade and sell goods here on Sundays, their day off. Over time, the market grew and grew, eventually being open seven days a week from morning til night. The colonial government made a strong effort to use local timber when constructing the wooden buildings around Georgetown, but for the steel and iron Stabroek Market, they outsourced the manufacturing to the Edge Moor Iron Co. in Delaware, the United States. The metal used to build the market weighs 635 tons and the hall is 7000m ² (80000ft ²). There are food stalls and vendors hawking anything and everything you can imagine.

The clock in the market’s distinctive tower was made in Boston and used to chime every thirty minutes. The clock has been out of order for years with few attempts at getting it up and running once more. Stabroek usually gets going around 7am, with minibuses congregating in the parking lot at all hours of the day and night. The market doubles as the main bus depot and most bus routes will take you to the market eventually. The bus to the airport departs from Stabroek- just ask around and the drivers will tell you which bus to take.

A word of caution: there is no such thing as a “full” bus. A driver will pick up any passenger on the side of the road, even if everyone is sitting on each other’s laps, as long as they can pay the fare! When I first arrived in Guyana and was en route from the airport to downtown, we came upon a group of 15-20 children who were on their way to school. Although every seat in the mini bus was occupied, the driver stopped and told them all to get in. Every adult now had a fifth grader on their knee as the bus hobbled forward for another ten minutes before they hopped off at their destination.

Parliament Building (Public Building)

The Parliament Building, which many locals simply call the Public Building, is home to the National Assembly and Library of Congress. It has a Neoclassical-Style design, with white columns, clear-cut geometric shapes, a central dome and a portico with arches. The greenheart wood used as a frame was covered with stucco to give the illusion of a stone edifice.

The Public Building opened in 1834 and was constructed completely with slave labor, an irony not lost on the people forced to build a governmental palace for officials who “owned” rather than represented them. In 1838, it was from this balcony that the proclamation outlawing slavery was read aloud to the people of Georgetown who had gathered on the Parliament’s front lawn below. One year later, 83 emancipated slaves marched to the Public Building, and with their collective savings purchased an abandoned plantation in what was to become the Victoria District of the capital, establishing the first real community for former slaves.

St. Andrew’s Kirk

Construction of St. Andrew’s Kirk lasted from 1811-1817, making this 200+ year old building the oldest religious institution still standing in Georgetown today. The Dutch laid St. Andrew’s cornerstone, but they ran out of money before they could finish building the church. They turned towards the growing Scottish Presbyterian population for a helping hand and the two groups shared the property for many years. St. Andrew’s was also the first church that allowed the African slave population to worship within its walls.

Smith’s Memorial Congregational Church

When Reverend John Smith was stationed in Georgetown in the early 19th Century, he immediately began ministering to the slaves on the various sugar plantations. In addition to preaching, he taught them how to read and write; his devotion to God was matched only to his support of the abolitionist movement. In 1823, Guyana saw the largest slave rebellion in its history and Reverend Smith was charged with inciting the uprising. He was later arrested, found guilty and sentenced to death. The verdict was appealed and he was eventually acquitted, but before he could be released, he died from disease in prison. In 1843, this church was built and named in his honor.

The Red House (Cheddi Jagan Research Centre)

We don’t know the exact date when the Red House was built, but many believe the original structure may have been lost to a fire or was at least vastly different from the structure we see today. The Red House was acquired by the government in 1925 and was used by various agencies until it fell into disrepair in the 1990s. In 2000, the house was restored and transformed into the Cheddi Jagan Research Centre.

Dr. Jagan was a career politician nicknamed the “Father of the Nation,” who served as President of Guyana from 1992-1997. He was the first Hindu and first person of Indian descent to serve as head of state outside of Southeast Asia. (If you fly into Guyana, you’ll enter through Cheddi Jagan International Airport, just south of Georgetown.) The centre inside has an exhibit of Jagan’s photography, as well as gifts he received from world leaders and dignitaries. The house gets its name from the red wallaba shingles that bedeck the building’s exterior; wallaba is a dense, tropical hardwood native to Guyana that produces a thick gum and oil mixture when cut. This concoction creates a natural protective barrier against insects and decay. Note the white Demerara windows jutting out from the wall that helped with air circulation in colonial times.

The Prime Minister’s Residence

Built in the mid-19th Century, this Tower House was designed in an Italian-Style for a wealthy shipping magnate who could watch for his cargo coming into port from the square cupola above. The government bought the house in the 1980s and it now is home to the Prime Minister of Guyana. You can’t enter the grounds, but you are allowed to take photos from across the street.

What a Wooden-ful World

In the weeks leading up to my trip to Guyana, I was really starting to feel the pressure mount. I’m all for going somewhere and being spontaneous, but I at least like to have some rough framework of what I’m going to do and have a sense of few places I should visit during my stay in a given capital city. I had pulled Georgetown from the deck and was coming up with nothing. Lonely Planet was a bust and online resources were turning up bupkis. Switching my tactic and casting my net into the architectural world was a game changer. I found Compton Davis’ book (thank you!) and suddenly my trip had purpose and a direction. Sometimes all you need is a jumping off point and soon everything starts to fall into place. Georgetown’s wooden colonial architecture is a true gem; part of me wants to shout it out to the world while the other half of me wants to keep it quiet and let this be a hidden gem for those willing to take a chance on the least visited country in South America, the Caribbean or wherever it is.