There’s no way around it: by and large, the past 100 years of Latvian history have not been happy ones. Like her Baltic neighbors, Latvia took advantage of the Russian Revolution in 1917 to declare its own independence in 1918. Kārlis Ulmanis played a major role in freeing Latvia from Russia’s grip and was rewarded by being installed as the new republic’s first prime minister. By 1934, Ulmanis had dissolved Parliament, suspended the constitution and was ruling Latvia as a dictator. (His legacy in Latvia is a complicated one, as historians must reconcile his revolutionary war hero status with that of the later authoritarian. Interestingly, his grand-nephew was elected President of Latvia in 1993, but I’m getting a little ahead of myself here…)

Latvijas Okupācijas muzejs (Museum of the Occupation of Latvia)

1940 and the onset of WWII saw the first Soviet occupation of Latvia. The Soviets ceded control of Latvia when Nazi Germany invaded in 1941, but they regained the territory by 1944 and kept the Latvian people under their thumb until 1991. The best place in Rīga to gain an overview of the 51 years of occupation is at the Latvijas Okupācijas Muzejs (Museum of the Occupation of Latvia), which details the hardships and horrors of the occupations, as well as the resistance carried out by the Latvian people. At the time of my visit, the museum was under heavy construction and a temporary exhibition space had been set up. Google maps might not be the most up-to-date source of information on the subject, so ask at your hostel before you head out in search of the museum.

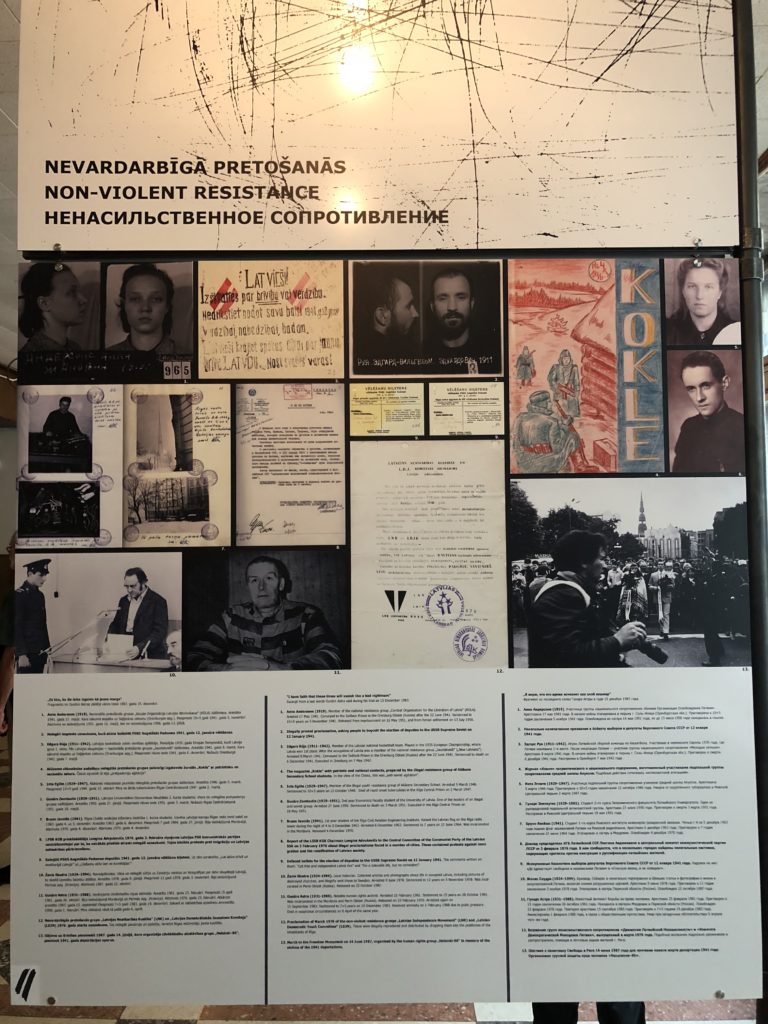

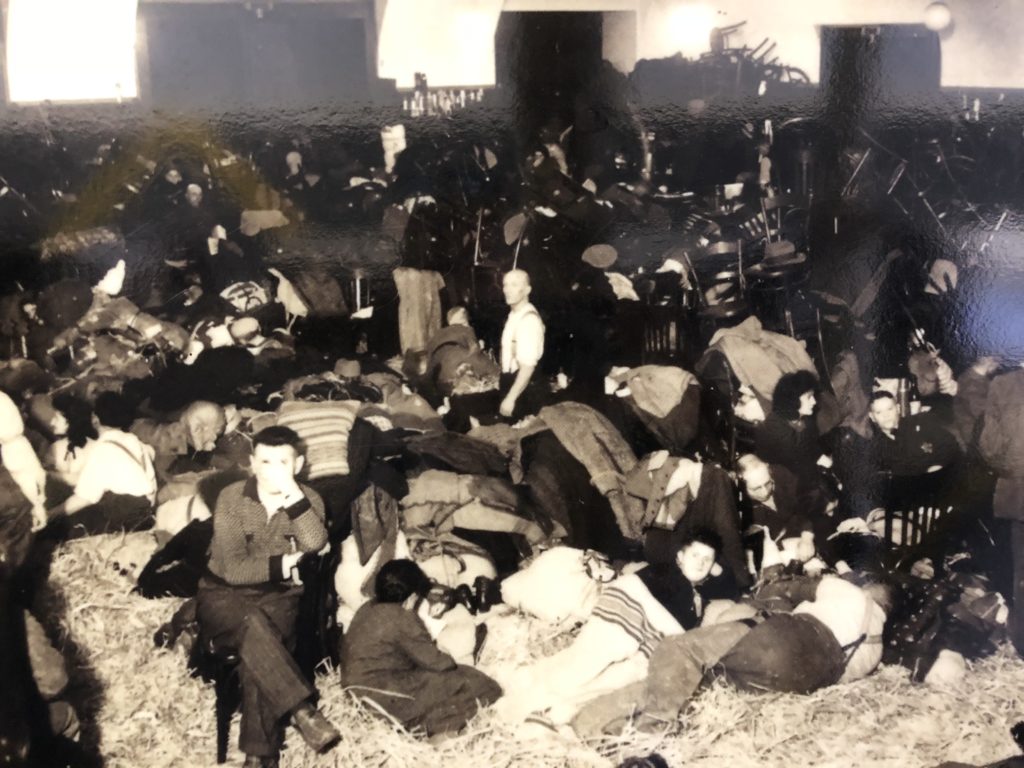

By the end of WWII, Latvia had lost one third of its population; 75,000 of those killed were Latvian Jews, which I will discuss in more detail below. Stalin enacted mass deportations to Siberian gulags for anyone he viewed as non-compliant. Latvian culture (in particular the language) was also suppressed under Soviet rule. All private property and businesses were confiscated by the state and a puppet government was installed to carry out Moscow’s bidding. Latvians resisted, of course, but if caught, penalties were severe and your entire network of friends and family would be found guilty by association.

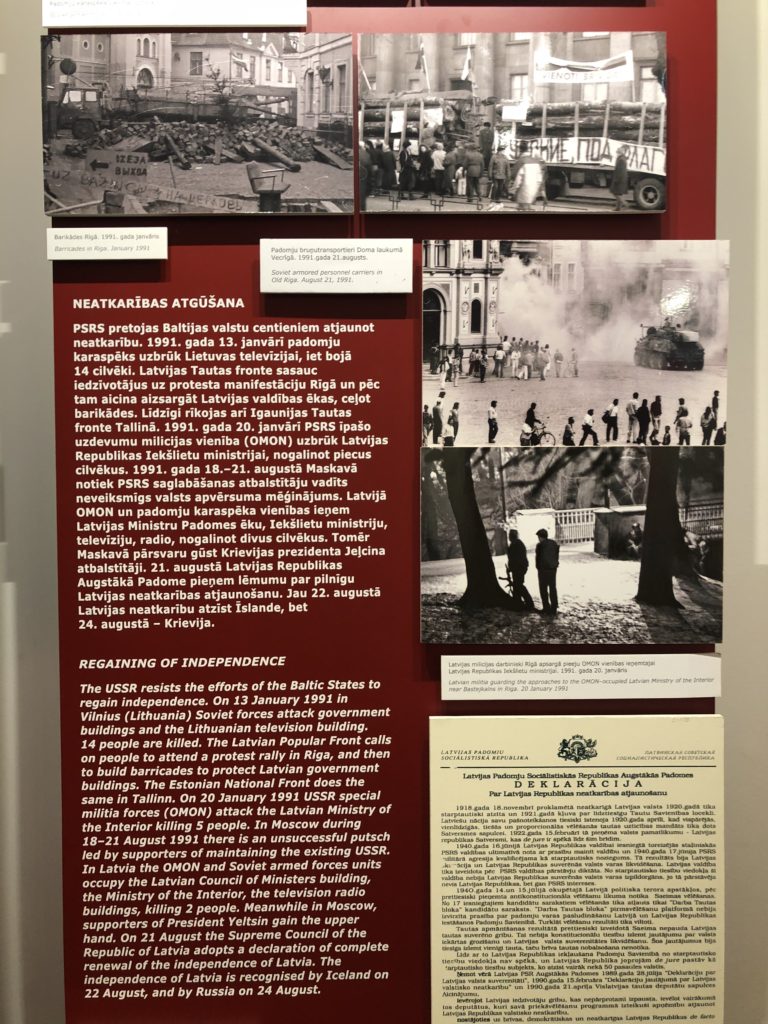

Unlike Estonians, who were able to regain their freedom from the Soviet Union without shedding a drop of blood, Latvians were not so fortunate. As the communist party weakened throughout the 1980s, the resistance grew stronger; Rīga became the epicenter of protests and demonstrations demanding independence. Moscow deployed troops and several Latvians were killed at the barricades they had erected throughout the capital. By August, 1991, Latvia had fully re-established itself as an independent nation and by 2004 held membership in the EU. The museum is a very sobering (and at times quite graphic) experience, but it’s a must-visit in Rīga if you want to understand the not-so-distant Latvian past.

Stūra Māja (Corner House/KGB Building)

Although the nicknamed “Corner House” may have a beautiful art nouveau exterior, it only serves as a facade to mask the atrocities that occurred within its corridors. During the first Soviet occupation, the Corner House was where anyone suspected of being an enemy of the state was brought for intense interrogation and/or torture. Executions were initially carried out onsite; by time the Nazis invaded Rīga in 1941, 186 Latvians had been killed in the dungeons.

During the second Soviet occupation, over 48,000 Latvians were detained and processed through the dreaded building. If not immediately sentenced to death, most prisoners were shipped off to gulags, where they were forced to live and work in terrible conditions. There was an old bit of dark humor amongst the citizens of the capital that the balcony of the Corner House was the only place in Rīga where one could see Siberia.

The exhibition that chronicles the brutality of the KGB, as well as those who stood up against the Soviet regime, is very informative and free to visit. The prisoner cells below can only be visited by guided tour and tickets should be purchased in advance as the English offerings fill up fast. It’s all heavy stuff, but if you want a first-hand look at what an oppressive government is capable of, then I suggest taking the tour and gaining a deeper understanding of what the Latvian people endured. And make no mistake: the greatest tool the KGB had was neither torture nor deportation, but rather fear. The KGB instilled a terror inside every citizen that they could be next to disappear for the slightest infraction, so best not to step out of line. Nothing can erase the pain and suffering caused by the KGB, but at least exhibitions and tours like those at the Corner House can spread the truth of what really happened- the first step to combatting fear.

Rīgas Geto un Latvijas Holokuasta Muzejs (Rīga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum)

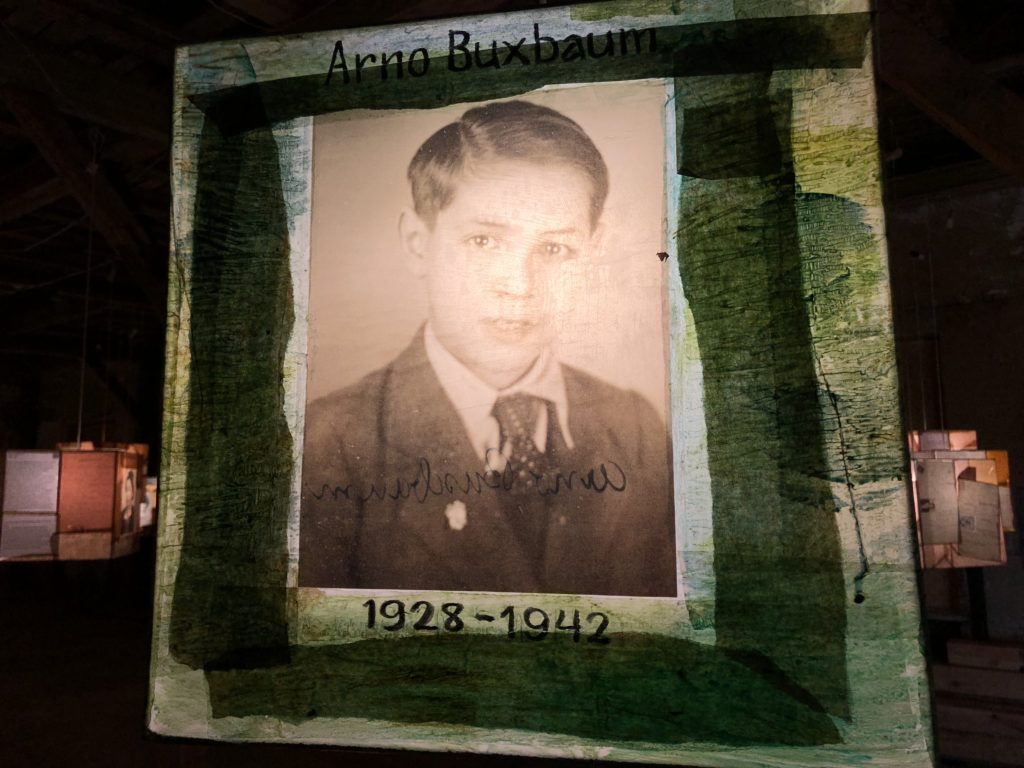

Perhaps the most powerful museum in all of Rīga is the Rīgas Geto un Latvijas Holokuasta Muzejs (Rīga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum), which lays out in vivid detail the plight of the Jewish Community during the Nazi occupation from 1941-44. The Rīga Ghetto was located in the Maskavas Forštate or Moscow District in the southeastern quadrant of the capital. The Nazis murdered almost 75,000 Latvian Jews and destroyed nearly all 200 synagogues that stood before the war. Only 185 Jews survived in Rīga by the end of WWII.

The centerpiece of the museum is the “Ghetto Street” wall that displays the names of every known Latvian victim of the Holocaust. Other exhibits show model recreations of the destroyed synagogues and typical living quarters within the 250 buildings of the Rīga Ghetto. Once the Nazis took control away from the Soviets, all of the Jews throughout Latvia were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to live in the Ghetto. This was the holding ground until they were shipped in train cars to be murdered. Other Jews from Eastern Europe were also brought to the Rīga Ghetto before meeting their fates, mostly in the forests outside the capital.

Several moving memorial displays have been set up to tell a few of the stories of those who lost their lives. The children who perished, separated from their loved ones, are the saddest of all.

Rīgas Horālās sinagogas Holokausta memoriāls (Riga Great Choral Synagogue Holocaust Memorial)

Not far from the Riga Ghetto Museum once stood the Great Choral Synagogue. Built in 1871, it was the largest and most influential center of Jewish culture in all of Latvia. On July 4, 1941, only three days after the Nazi Army marched into Rīga, the doors of the synagogue were barred in the midst of a prayer service. The Nazis then poured fuel over the place of worship and destroyed the structure, burning everyone inside alive. 400 Jews were killed during that afternoon as synagogues all over Rīga were burned to the ground.

During the second Soviet occupation, a grassy park covered up the synagogue’s foundation, but in 1993, the ruins of the massacre site were unearthed and turned into a memorial park. Today the names of those killed rest on stone tablets, facing the sacred spot of their deaths.

What should Rīga do with its Soviet legacy?

Turning the former KGB Building into a museum wasn’t a very controversial idea, but deciding what to do with all the Soviet monuments and statues around the capital has set off debates and reopened many old wounds that were just beginning to heal. Should these monuments remain to remind people of the past, or do they allow the villains of history to retain some of their glory? Are these reminders simply too painful for the survivors to be forced to look out day in and out? Is any purely artistic love for these pieces in and of itself an abhorrence? What about an ironic love? The Uzvaras piemineklis (Vicotry Monument) is the lightning rod in this debate, as it continues to stand to this day.

This so-called “Victory” Monument sits in a complex reached by trams 1 or 2 from the city center. It was erected to commemorate the Red Army’s defeat of the Nazis, “liberating” Latvia and- oh, that’s right- signaling the onset of the second Soviet occupation. It would be one thing if the monument had been unveiled in the years immediately following WWII, but the Soviet government didn’t construct the Uzvaras piemineklis until 1985! The real intention was to let the Latvians know that, “Hey, we’re still here and still in charge.” Of course, by this time no one was under the illusion that the Soviets were liberators or had their best interests at heart; in actuality the resistance was stronger than it had ever been and only continued to grow mightier by the day. With the Soviet government in Moscow crumbling and nary a cent in the coffers, deciding to build this monument was like ten slaps to the face from all sides.

Multiple groups have attempted to bomb the monument; others have taken a more peaceful route and gathered signatures for the government to dismantle their hated behemoth. The pro-monument side insists that this is part of Latvia’s history, whether you like it or not, and destroying the monument will only cause people to forget the struggles the Latvian people faced sooner. If the monument continues to stand it will ensure that generations of natives and tourists alike will ask the story of this monument and learn how Latvia gained its independence yet again.

The 79m (260ft) tall obelisk adorned with stars top is locally joked to be Moscow giving the middle finger to Rīga. Whether you stand in awe or feel like giving the finger right back is up to you.