What is Macedonia and where, if at all, does it exist today? This may seem like a simple question, after all, something surely either exists or it doesn’t, but as the hundreds of thousands of lives that have been lost over the past six hundred years trying to solve this complex equation in the Balkans can attest to, the answers are anything but easy. Skopje, North Macedonia’s (“Macedonia’s” third official name change since declaring independence from Yugoslavia in 1991) capital is a wonderful place to explore Macedonian identity through a series of historic neighborhoods, museums and a bizarre 21st-Century-monument-building project.

House of Macedon

If I had to pinpoint the origin of the tension between Greece and North Macedonia, I would have to go way, way, way back to 359 BC when King Philip II took the throne in Macedonia. Viewed by the Greeks as their unruly neighbor to the north, Philip II wanted to rehab the Macedonian image and started incorporating elements of Hellenistic culture into Macedonian cities and daily life. He dreamed of uniting all the warring Greek tribes, a dream he did not see realized before his death, thus necessitating his son, Aleksandar III of Macedon (or known by his Greek title, Alexander the Great) to follow through with his father’s vision.

Although Aleksandar was ethnically Macedonian by birth, he unified the Greeks and expanded their empire to include present day Egypt, Bulgaria, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Eastern India. Both North Macedonia and Greece lay claim to Aleksandar’s heritage and disputes involving monuments and historical legacies continue to this day. Every chance for one government to needle to the other is a chance taken. Skopje International Airport was once named after Aleksandar and Universal Hall will shortly have its name changed to Aleksandar the Macedonian Center.

Ottoman-Era Skopje

Known simply as Kale, the Turkish word for fortress, this former military installation offers some of the best views of Mount Vodno to the south and Skopje below. The first fortress was built on this hill in the 6th Century, but the existing structures are from the 10th and 11th Centuries when Macedonia was under the control of the Byzantine Empire. In 1392, Ottoman troops captured Kale and thus began 520 years of Ottoman rule.

During the Ottoman Era, the fortress flourished and became the official barracks for the Ottoman army; the barracks later were used by the Yugoslav Army between 1945-91. Over the past decade, extensive archeological digs have commenced all over the fortress grounds. Woodwind instruments and ornaments dating back to 3000 BC were unearthed, as well as the largest collection of Byzantine coins ever to be discovered in a single location. Kale is a treasure trove yet to be fully explored.

Today most of Kale lies in ruins, having barely survived the bombings of both World Wars and the devastating earthquake of 1963. Preservation efforts have intensified in recent years; the fortress is free to visit and is a great place to understand how the Ottomans controlled Skopje during their centuries-long reign.

Стара чаршија (Old Bazaar)

The largest bazaar still operating in the Balkans, Skopje’s Old Bazaar was the hotspot in Ottoman Macedonia. At its height, the bazaar contained a market, thirty mosques, several Turkish baths and inns. Today you can find souvenirs aplenty, restaurants and trendy nightclubs. The demographics of North Macedonia today are about 75% ethnically Macedonian and 25% ethnically Albanian; the Albanian minority has taken up residence in this quarter of the city.

The market is fun to walk around, but honestly I didn’t find the restaurants here to be anything to write home about and the food is way over-priced. I preferred to eat in the Карпош (Karposh) district, just west of downtown. There are a bevy of outstanding restaurants here including some strictly vegetarian/vegan joints that I couldn’t get enough of. Go to the Old Bazaar’s market to buy your t-shirts, flags and magnets, but go a little farther afield for your Macedonian eats.

Мустафа Пашина Џамија (Mustafa Pasha’s Mosque)

Of the thirty Otttoman-era mosques built in the Old Bazaar, Mustafa Pasha’s Mosque is the most culturally significant. Completed in 1492, the mosque sustained considerable damages during the 1963 earthquake; the Turkish government donated money to have it repaired in the aftermath. Mustafa Pasha was one of the sultan’s right-hand men and had the power and prestige to have such a mosque built in his honor. Mustafa’s daughter is buried in a tomb next to the mosque.

Hans and Hammams

Surrounding the market in the Old Bazaar were two Ottoman-era staples: the Han and the Hammam. A han, or caravanserai, was an inn found all over the Muslim world where travelers and merchants could purchase a filling meal and find a cheap bed for the night. Only three hans are still standing in the Old Bazaar today, each of which houses a small museum related to life in Ottoman times.

Hammams, or Turkish baths, were also common throughout the empire. The one pictured above was a rare double bath, one side being for men and other for women. Čifte Hammam even had a pool just for Skopje’s Jewish community so they could perform any sacred rituals here unbothered. Today the hammam houses a branch of the National Gallery of Macedonia. It seems that every historical building in the bazaar has been turned into a museum and you could spend the better part of day visiting each one if you so desired.

The Cultural Melting Pot of Stara Čaršija

The tradition of Ottomans fusing their culture with the people they conquered lives on today in Stara Čaršija. All signage is inscribed in three languages: Macedonian, English and Albanian. For the first twenty years after North Macedonia declared independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, tensions ran considerably high between the Macedonian majority and the Albanian minority. While the Macedonians were celebrating their freedom, the Albanians felt like they had jumped from the Yugoslav frying pan into the Macedonian fire. Relations have dramatically improved over the past decade between the two groups and an act as simple as including the Albanian language on street signs speaks volumes.

20th-Century Skopje

Everything up until this point has been setting the stage for the 20th-Century collision course that the Macedonian people were on against almost every other power in the Balkans. The most comprehensive place to learn about this era of history is the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle. While the exhibitions are certainly a bit biased towards the North Macedonian government, this museum, which opened in 2011 as part of the “Skopje 2014” project, can still give you an excellent background on the many conflicts experienced in the region.

The museum is divided into thirteen units, each comprised of massive murals of scenes from Macedonian history as well as over one hundred wax images of famous historical figures, many of whom were martyrs for the Macedonian cause. You can wait for a ninety-minute guided tour, but all of the signage is also posted in English, so I chose the self-guided option instead.

The first exhibition deals with the 1903 Ilinden Rebellion, where Macedonians banded together to expels their Ottoman occupiers. The rebellion was successful for about ten days before the Ottomans retook control of Macedonia, but the seeds of freedom were planted and the once-small cracks in the Ottoman armor had suddenly deepened.

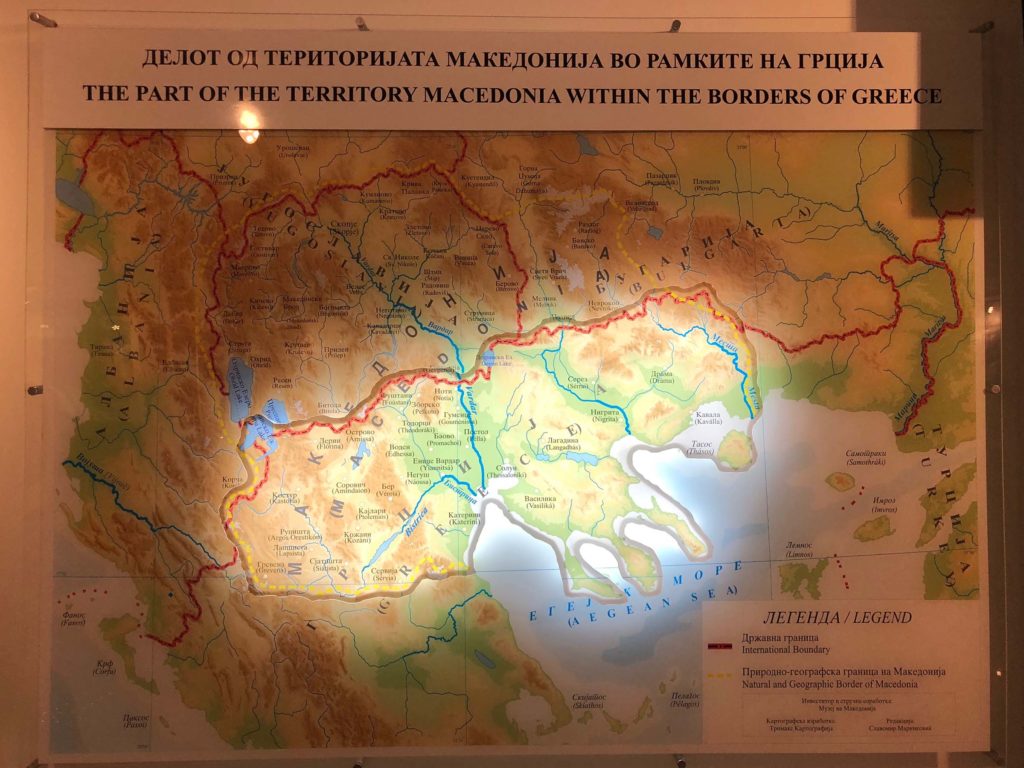

Now, when I mention “Macedonia” at this time, what area do I mean? Macedonia contained the regions of present-day North Macedonia, northern Greece and a large chunk of western Bulgaria. These lands admittedly had changed hands many times over the past millennium and since the 1400s, all of it had belonged to the Ottomans. Not only were these nations eager to declare their independence, but they were preparing for a land grab to snatch back as much of this contested territory as possible when the Ottomans fell.

In 1912, Serbia and Montenegro aligned themselves with Greece and Bulgaria (poor Macedonia was left out in the cold, although their soldiers did fight alongside those in the other armies) and defeated the Ottomans in the First Balkans War. Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria divided up Macedonia, each taking a piece. (North Macedonia, the Serbian chunk, was initially called South Serbia.) Serbia and Greece felt that Bulgaria had taken too large a piece of Macedonia, inciting the Second Balkans War in 1913, where the former allies turned on Bulgaria and took back large portions of Macedonia for themselves.

Macedonia became something like the child of divorce with parents continually fighting over custody. The ping-ponging back and forth harmed no one more than the Macedonians stuck in the middle. During WWI, Bulgaria once again took possession of Macedonia between 1915-18. In 1918, Western European powers handed the northern half back to Serbia, which became incorporated into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and the southern half back to Greece. WWII: wash, rinse and repeat. Bulgaria takes control; the north and south are eventually returned to Tito’s new Yugoslavia and post-war Greece respectively.

Need a moment to catch your breath? So did the Macedonians.

I’ll save the fate of the Greek portion of Macedonia for later in this post, but let’s continue on with North Macedonia’s journey for now.

From 1945-91, North Macedonia was known as the SRM, or the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, which, along with the present-day nations of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and Kosovo, made up the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Josip Broz Tito was declared president for life, and he held the Slavic republics together until his death in 1980. Soon thereafter, the economy tanked and in 1991 Macedonia, Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia & Herzegovina declared their collective independences from the former socialist super power. Unlike its neighbors, Serbian troops left Macedonia alone and they were the only nation to leave Yugoslavia without shedding a drop of blood.

Independence only brought about more problems for the Macedonian people. In the 1991 Declaration of Independence, Macedonian leadership called their new nation the “Republic of Macedonia.” This really ticked off the Greeks. The government in Athens viewed this as a ploy to reunite the the northern half of Macedonia with the southern half still under Greece’s purview. Attempts by the Republic of Macedonia to join the United Nations were blocked by Greece; “we won’t let you in unless you change your name,” they responded.

In 1993, the Macedonian government settled on a new name, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia or FYROM for short. Under this name they were admitted into the UN, but once again were blocked by Greece from joining the EU. Now this new name was no longer good enough, all the while periodic demonstrations broke out in Skopje demanding that the government reunite the FYROM with southern Macedonia, even if that meant war with Greece. After years of political negotiations and backdoor deals, a new compromise was reached: in 2019 the FYROM became The Republic of North Macedonia, and proceedings are underway to admit North Macedonia into the EU.

Now, the President of North Macedonia wants to make something very clear: even though the country is called North Macedonia, the people are not to be referred to as North Macedonians, nor should any adjective be used to describe the culture of the country that has the word “north” in front of it. (You didn’t know you were going to get a lesson in semantics when you started this post, did you?) They are still the Macedonian people and their language is Macedonian and the culture is Macedonian. The only difference is they live in North Macedonia. Got it?

Музеј на Македонија (Museum of Macedonia)

This is one of the most difficult-to-find museums I’ve ever visited. I can’t even tell you how I got inside. There are signs pointing you toward the museum, and it’s marked in the correct spot on Google maps, but you can only enter the property through a tiny opening in the fence- one that definitely does not look you should be using it to enter. After I walked in circles for twenty minutes looking for the entrance, some giggling children finally pointed me in the right direction.

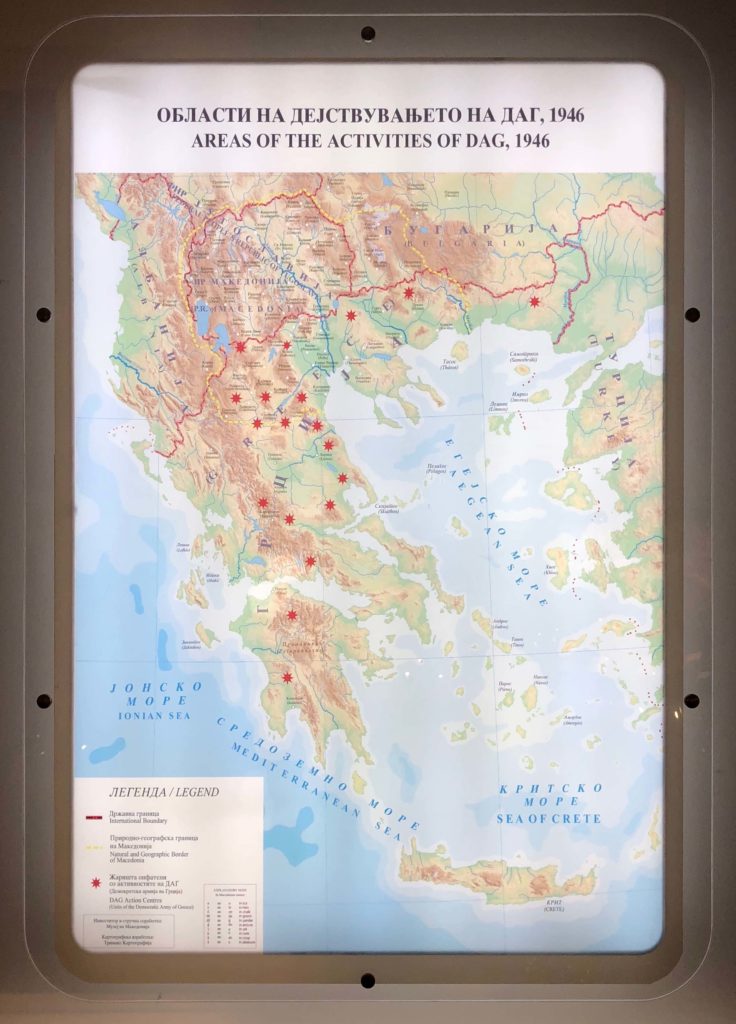

The Museum of Macedonia is now divided into two sections: history, and ethnography; the archeology department has been moved to its new location on the Vardar River. Of interest in the history section is the in-depth look at the Greek Civil War from 1946-49 between Greece and the southern section of Macedonia. At the close of WWII, after the Allied Powers returned North Macedonia to Yugoslavia and the southern piece to Greece, there was push by Tito to unite both halves of Macedonia and incorporate the southern half into Yugoslavia.

The Greek Civil War may have been fought on Greek soil, but it was the first battle of the Cold War, played out in the war rooms of the US, UK, USSR and Yugoslavia. The US and UK heavily financed the Greek Hellenic Army, providing them with copious amounts of supplies and weapons. Tito backed the Democratic Army of Greece (DAG), which, despite its name, was led by communist forces. When Tito saw that the DAG would never be able to win the war with Yugoslavia’s assistance alone, he turned to Stalin and the Soviet Union for aid. Stalin refused to get involved and this forever caused a rift between Tito and the USSR.

The DAG was defeated in 1949 and with it died any realistic hope of the reunification of Macedonia. Of course, the other side of the story is that Greece feels like this has always been their land going back to the days of Alexander the Great, and although they recognize the large Macedonian majority in the north, it would take World War III to make Macedonia whole again.

Етнологија на Македонија (Ethnology of Macedonia)

Visiting the Ethnology of Macedonia exhibit almost had an urbex (the purpose of traveling to visit abandoned buildings) quality to it. Apparently this section of museum has been in a perpetual state of renovation for years. Unlike the history department, no one was in the ethnology building and the ticket taker had to turn on all the lights for me. Some traditional costumes were on display, but many cases sat empty. It was clear that this area had not be touched since Yugoslav times. It was definitely like going into a time warp and visiting Tito’s Socialist Republic of Macedonia, when the museum was called the “People’s Museum of Macedonia.”

In addition to clothing, the department also showcases models of various rural dwelling styles, agricultural tools, fishing boats and exhibits on how holidays are celebrated in the region. There’s very little signage so your mileage may vary, but it’s worth a quick look around if you’re already on the museum grounds.

Note: Since my visit, the museum has been renamed the Музеј на Република Северна Македонија (Museum of the Republic of North Macedonia)

Музеј на Современата уметност (Museum of Contemporary Art)

This socialist brutalist beauty, built in 1970 and designed by Kiril Muratovski and Mimoza Nestorova- Tomic, is right up the road from the Museum of Macedonia. Now, why is this (brilliant) museum buried 2/3 of the way through this post? Where’s my in-depth look at modern and contemporary art in Skopje? I fear I have let you down, but hopefully my excuse will say more about the museum than any collection of photos ever could.

When I returned to my hostel in the evening (shout out to Urban Hostel!), I flipped through my photos, like I always do, while journaling before bed. I saw the above photo, the last I took before entering the museum and then the next picture was of the mountains behind the museum. I spent close to three hours in this museum and didn’t take a single photo? Yes, that’s right. I was so enthralled by Black Raw Memory and the rest of the collection; I was so in the moment and caught up in the art that any thoughts of this blog flew right out the window. I was at one with the Macedonian contemporary art, forcing documenting my experience to become secondary to experiencing it. Now, if that isn’t a solid recommendation for a place, I don’t know what is!

The museum has an interesting history. It was founded in 1963, the year of Skopje’s great earthquake that destroyed the 80% of the city. The international art community quickly rallied around the museum. While the new building was being constructed, a convention was held in New York encouraging artists from all over the world to create paintings and sculptures that would exclusively be shown at MoCA. Pablo Picasso painted his famous “Head of Woman” specifically to donate to the museum and other artists followed suit. This brought much international acclaim to the institution and helped get it back on its feet after the natural disaster. Today half of the museum is devoted to Macedonian art and the other half is given over to the artists who generously gave to the museum in their time of need.

“Skopje 2014”

I’ve dropped a lot of hints about Skopje 2014 over the past two posts, so let’s dig in and see what all the fuss is about. Although I did not conduct a scientific poll of every resident of Skopje, it’s no secret that Skopje 2014 was highly controversial and disliked by many citizens in the capital.

Contrary to what the name suggestions, the initiative known as Skopje 2014 began in 2010 by the local government and was “completed” four years later. The purpose of the project was as follows: Skopje’s claim to fame as the city with the most socialist brutalist architecture by square kilometer didn’t sit well with the mayor who was desperate to boost tourism and bring Skopje back to its ancient Aleksandar-III-of-Macedon roots. New buildings would be designed in Ancient Macedonian/Greek/Roman styles and statues would be erected all over town of heroes from this time period as well.

Putting aesthetics aside for a moment, the price tag was a sucker punch to the citizens of Skopje. Initially priced at 80 million euros (90 million dollars US), by 2014, the final bill came to a whopping 500 million euros (565 million dollars US). Hundreds of (tacky) statues and a handful of buildings later and all of this money down the drain. The average Macedonian makes about 300 euros (339 dollars US) a month, so imagine how angry they were that their taxes were being funneled into this nutty project instead back into the community to help the people. (Of course, the mayor believed this would bring in tourists, but talk about a weak excuse for spending in this kind of excess.)

There’s something very kitschy about these monuments and buildings. They are meant to look old and historic, yet when you get close enough you can obviously see they are only a few years old. You can walk through the Acropolis in Athens and know that it was built in 500 BC, but would anyone in Skopje be fooled into thinking these statues weren’t erected until 2011 or 2012? Skopje 2014 is like the Disney-World-Epcot-Center version of Ancient Macedonia. Brand-spanking new, ready for a photo op and to sell a few souvenirs.

Ultimately, over 130 new statues were placed all over Skopje, especially on the bridges that span the Vardar River. Victorian-style lamp posts line the central square, and oh yes, each lamp is equipped with speakers that pump music into the nighttime air. I swear I heard The Blue Danube Waltz one evening, and whatever that has to do with Macedonian culture is anyone’s guess!

After the 1963 earthquake flattened Skopje, the need to reinvent the capital was a necessity, not a choice. Kenzo Tange’s vision to transform Skopje into a socialist brutalist concrete Mecca had to be accepted in order for the city to function. Skopje 2014 was an unwanted reinvention forced upon the city and its inhabitants. The metamorphosis after the earthquake was organic; this new one was anything but.

As much as the local politicians wanted to cry out that they were promoting Macedonian heritage and making the city more appealing to tourists (I’ll stick to the brutalist Central Post Office, thank you very much!), it seemed like the real motive was to get in as many jabs at the Greeks as possible. Monuments like “Warrior” and “Warrior on a Horse” was obviously tributes to King Philip II and Aleksandar III, but this way when the Greek government complained, Skopje could play dumb and say, “This is just some guy on a horse. What are you getting so bent out of shape about?” (A plaque has since been added to the base of the “Warrior on a Horse” admitting it is Aleksandar so as not to insult anyone’s intelligence.)

This statue of the Gemidzii was a two-for-one special, angering both the Greek and the Bulgarian governments. The Gemidzii was a group of anarchist freedom fighters. Born in Bulgaria, but ethnically Macedonian, the group led a bombing campaign against Ottoman strongholds in Thessaloniki, the major city of southern Macedonia that is today part of Greece. The group’s victories against the Ottomans are claimed by all three nations, but Skopje was the first to build a monument in their honor, proclaiming “dibs” on the national heroes.

Two pairs of lions were placed at either end of the Goce Delcev Bridge in 2010. The beasts were instantly mocked by the citizens as trying too hard to replicate Western European aesthetics. A school lunch program for underprivileged children was axed during the same time period, and people would joke that the lions ate the kids’ lunches.

And then the controversy grew. The artists were asked on live Macedonian television how much they were paid for each statue. The artists refused to comment and a furor arose. People demanded that the government be transparent with the total cost of each monument, which they eventually disclosed to be 2.3 million euros for the set of four lions. The work was valued by the square meter, and here’s the final twist: when the statues were actually measured, they each didn’t add up to their purported dimensions. In fact, each lion and its pedestal was about 130,000 euros worth in area shorter than they should have been. The only question left was who pocketed the extra money? The politicians or the artists?

And yet, despite everything I have written above, here’s my deep-dark secret, and one I shared with many others I chatted with in hostels all over the Balkans: I kinda sorta love Skopje 2014. I don’t like that money that could have enriched the lives of the people was misspent, but the end result, in all of its tacky, gaudy glory, is hard to look away from. The whole experience of walking around at night, listening to the music, seeing all the faux-antiquity marble statues is more than a little surreal and gave me the feeling like I was strolling around a carnival fun home. Despite itself, the works of Skopje 2014 have melded with the socialist brutalist buildings and the Ottoman bazaar and the history lessons at the Museum of the Republic of North Macedonia. This wacky melange is what makes Skopje so fascinating and special. There’s no other place like it in the Balkans, and likely the world.

Let me wrap this one up with a look at the infamous “Warrior on a Horse,” which yes, changes colors at thirty second intervals. Only in Skopje. Only in Skopje.