Despite already holding the title of political and economic hub of Iceland for well over a century, it wasn’t until the 1950’s when Reykjavík could be labeled as anything more than a large village. Over the next 50 years the capital transformed into a true metropolis; now a third metamorphosis has occurred, turning Reykjavík less into a city and more into one enormous modern art expo. Some might attempt to attribute my impression of this art lover’s Mecca to the fact that I happened to arrive at the start of the Reykjavík Art Festival, but I have a feeling that this is the city’s new status quo.

The art is also so Icelandic. Let me explain. With the exception of The Whitney, when you visit an art museum in New York you can be wowed by the European Renaissance Masters or check out a cool new special exhibit from Japan at The Guggenheim, but this art tells you very little about New York, except perhaps that we are an international city. On the other hand, the art in Reykjavík is all about Iceland. The relationship between people and nature is a prime focus; daily rural life is also a frequently explored subject. The abstract and impressionistic approaches to both painting and sculpture add to the revelations of the national psyche that the subject matter brings to the table. Iceland is an isolated nation and Reykjavík is the most northerly capital in the world. The sun barely sets in the summer and darkness allows only a few hours of daylight during the winter. Icelanders seem to march to the beat of their own quirky drummer, but in a reserved, respectful kind of way. All of this is deeply reflected in the modern/contemporary art scene, and the more I soaked up, the more I began to understand the wonderfully off-beat populous.

There’s too much to write about in one post, so here in Part I I’m going to kickstart the discussion with the Reykjavík Art Museum. The Reykjavík Art Museum is really three different museums, spread out over the city. One ticket can get you into all three locations for a day; the entire institution (as well as the National Gallery, National Museum and much more) is also included on the City Card pass, which you can purchase at the Tourist Info Center for 24, 48 or 72 hour increments. Each of the three museums normally focus on three of the most influential Icelandic artists (Erró, Jóhannes Kjarval and Ásmundur Sveinsson), but two days before I arrived in the city, a special exhibition called “Einskismannsland” (No Man’s Land) had taken over two of the museums.

Hafnarhús

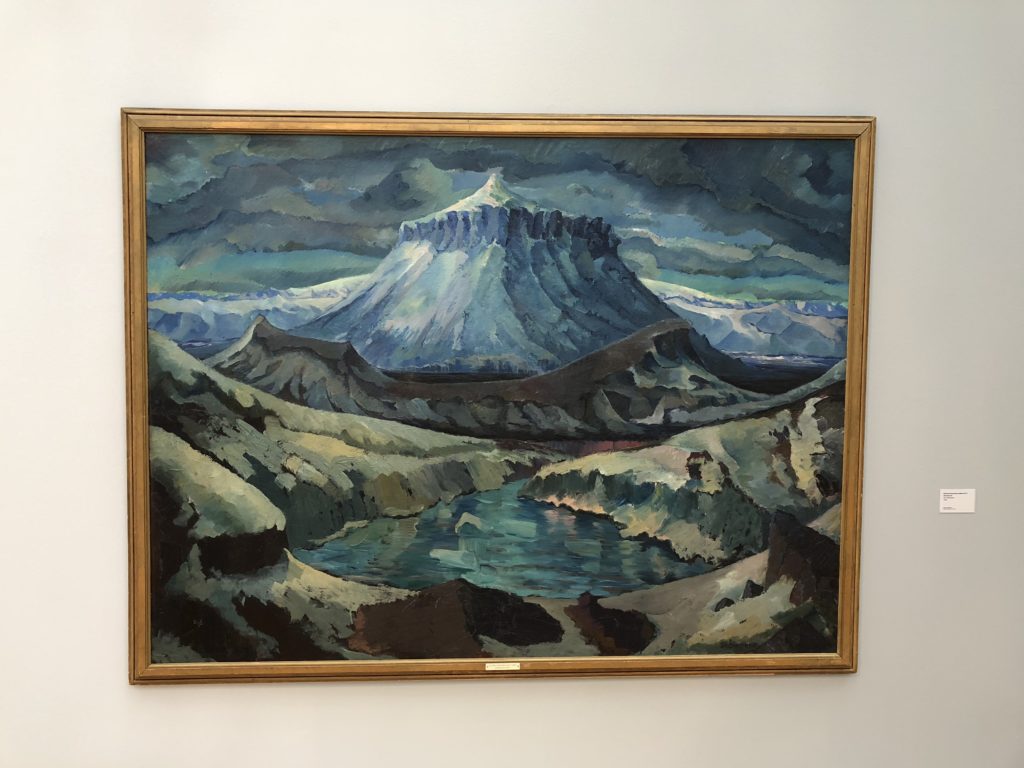

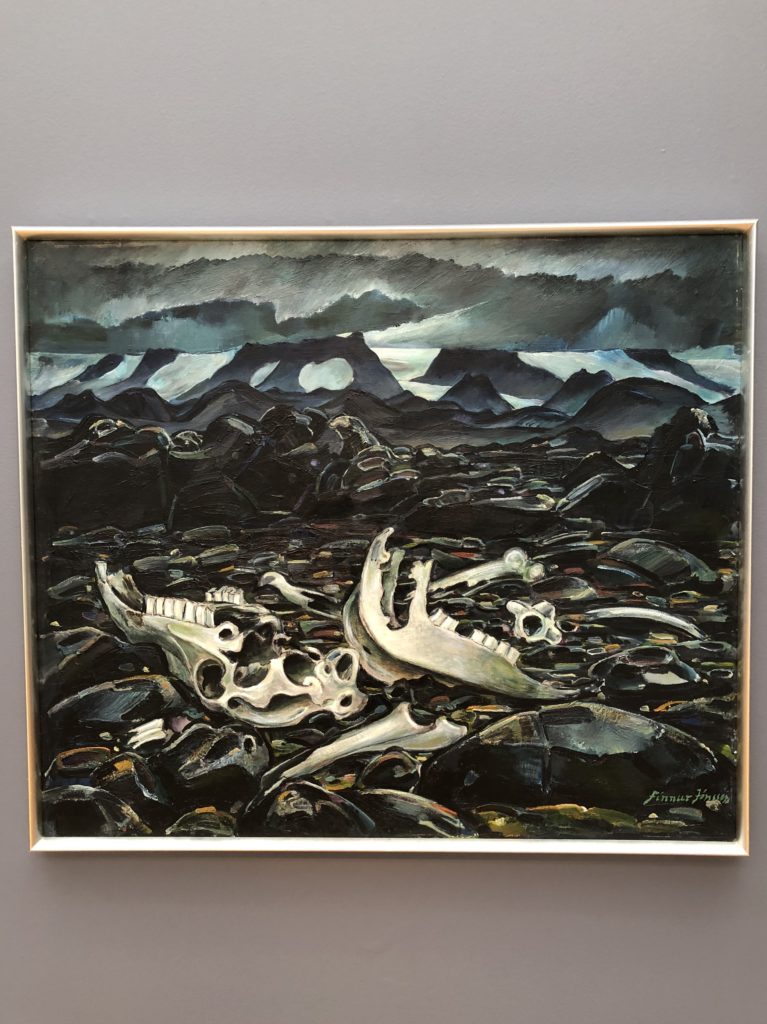

Located directly on the harbor in downtown Reykjavík, Hafnarhús usually keeps Erró’s work front and center after the Icelandic artist donated a large portion of his output to the museum over the past decade. My disappointment at missing the Erró exhibit quickly dissipated as I made my way through the first gallery of “No Man’s Land.” During the early 20th Century, Icelandic photographers and painters began to focus on the Highlands as a source of inspiration. Up until this point, large portions of the Highlands had been left relatively undisturbed and unexplored. The glaciers, volcanoes, geysers and rugged terrain were cause for both wonder and fear, which all is reflected in works from the early 20th Century.

The exhibits in Hafnarhús are more interested in man’s relationship with nature in the 21st Century. Fear now flows in the other direction, with the natural world being far more scared of humans than humans are of the land. As Iceland’s resources are pillaged throughout the Highlands and a flood of tourists threaten to overwhelm the delicate ecosystem they so want to show off on their Instagram feeds, these artists play the role of activist just as much- if not more so- than painters and sculptors.

I loved these two pieces demonstrating how technology and industry have encroached on the water system in the Highlands. The cascading fluorescent-bulb waterfall was adorned with speakers that played actual recordings of waterfalls the artist taped in the field. When you closed your eyes, it sounded natural and pure, but we can no longer look at a waterfall without seeing it as a tool to harness for electricity and power. Likewise, the second installation showed the literal shredding man has done to the ecosystem, affecting animal and plant life along with it.

”No Man’s Land” was a full-on multimedia event. If your idea of an art museum is a bunch of dimly lit paintings in a dusty space, then Hafnarhús will be a nice shake-up for you. These hand-held videos chronicled several artists as they hiked around the Highlands. Intense traditional Icelandic drumming filled the gallery and the primal, percussive sounds both fit right in with the scenes of the landscape and felt a world away from the shaky footage.

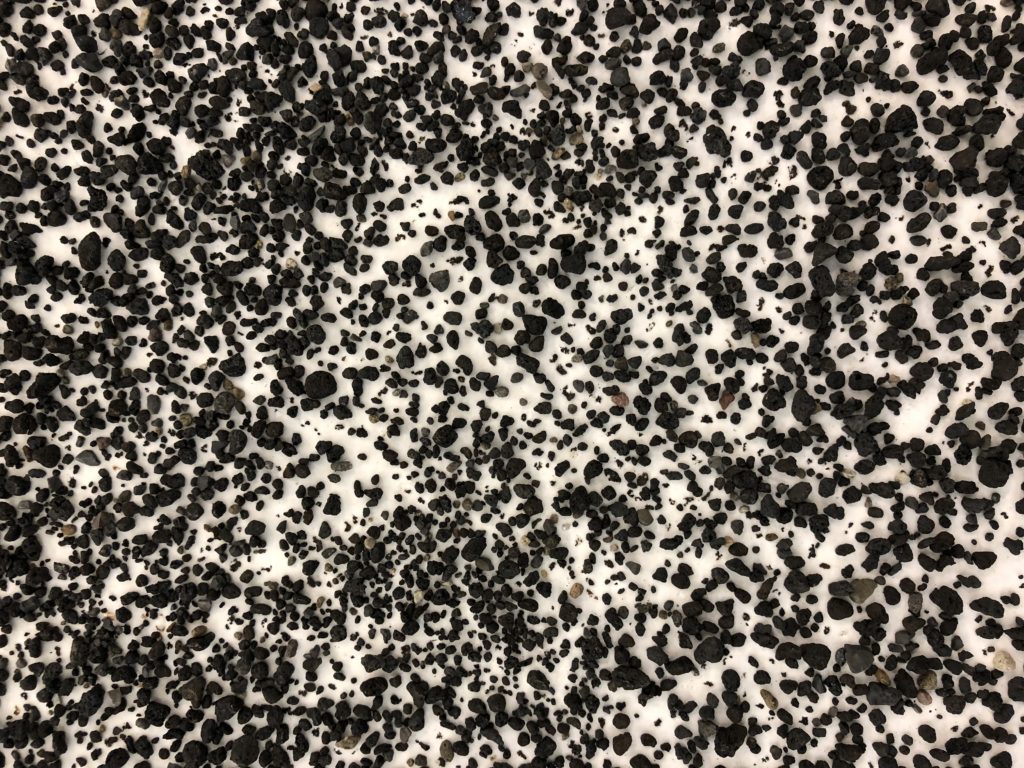

The Highlands acted not only as inspiration for the art, but sometimes the land literally was the art. Countless tiny pieces of volcanic rock and ash were glued directly to the wall in one of the upstairs galleries at Hafnarhús. As I entered the room, I mistakenly thought someone had simply spray painted a large, gray rectangle on the wall, but as I neared the piece I began to make out a raised texture, creating an effect similar to Seurat’s pointillism, except with earth instead of a paintbrush, and yes, a few phrases of Sunday in the Park With George may have been sung for good measure.

Kjarvalsstaðir

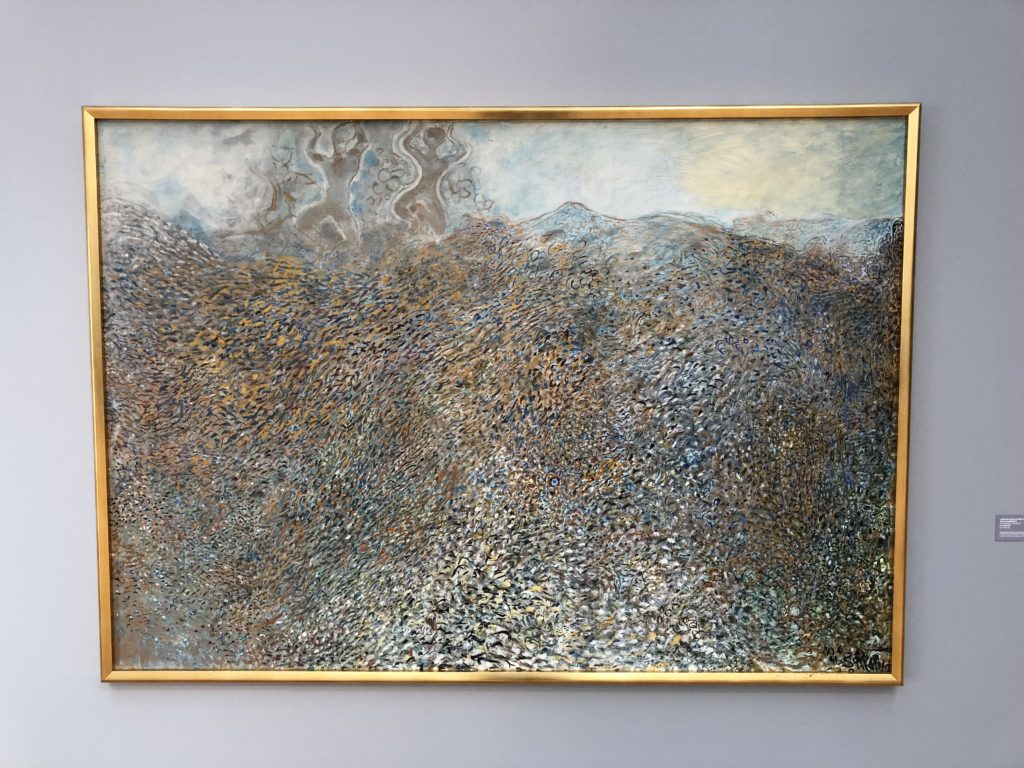

Kjarvalsstaðir is named after Jóhannes Kjarval, one of the most well-known painters in Iceland. Due to his upbringing on a farm, Kjarval developed a strong connection to his natural surroundings and the nation’s rugged landscapes were often his subject of choice. This division of the Art Museum naturally showcases his work, and several of his pieces are interwoven into this half of “No Man’s Land.” Unlike Hafnarhús, Kjarvalsstaðir‘s side of the story doesn’t warn about man’s destruction of nature, but rather celebrates its majesty and awesome power. Instead of ultra-modern installations, the works here are mostly paintings from the first half of the 20th Century.

Excuse the crooked picture angles, but it can sometimes be difficult to photograph a painting and avoid any glare!

Interwined with both the fear and awe reflected in these paintings, is the mystic belief in trolls, elves and other hidden people that were long held by Icelanders (and still are in certain areas). For centuries, the final frontier wasn’t space, but the Highlands. The unexplored territory gained its own set of super powers, commanding a respect that is lost on modern cynical and skeptical ways of thinking.

If you wish to pay your respects to Kjarval, it’s too late to do it in person as he passed away in 1972, but you can visit his grave in the Hólavallagarður cemetery near downtown Reykjavík.

Ásmundarsafn

I shouldn’t play favorites, but if I had to choose, the Ásmundarsafn would be my favorite of the three museums. The building itself was once the home and studio of Ásmundur Sveinsson, who along with Einar Jónsson, is Iceland’s most revered sculptor. Ásmundur had a prolific career, producing works for over six decades. When he died in 1982, his residence and surround garden were turned into a museum, giving the public a venue to view his sculpture.

Ásmundur’s most famous work may be the Vatnsberinn (Water Carrier) seen at the top of this post. He created the sculpture in 1936-37 as a would-be centerpiece for downtown Reykjavík; a commissioned exaltation of the Icelandic woman. People were expecting a classic Greek or Roman interpretation of female beauty. They thought they were getting Venus on a clamshell and Ásmundur gave them a plain, middle-aged woman, hunched over by the weight of two pails of water. Ásmundur thought this encapsulated the hardworking spirit of Icelandic women, but city officials were not amused and the statue was placed on a hill on the edge of the city.

By the 1970’s, Icelandic women had formed a group called the Red Stockings, which demanded equal pay for women, as well as better access to birth control and other reproductive rights. On October 24, 1975, 25,000 women (out of Iceland’s total population at the time of 220,000) went on strike, refusing to not only work, but cook, clean or take care of their children for the day. The women marched through Reykjavík, many with signs of the Water Carrier, which had become one of the symbols of the movement. Iceland went on to be the first nation in the world to elect a female president and in 2011 the Water Carrier completed the long overdue journey to her rightful spot in the city center where she can be seen today.

Aside from taking in the sculptures themselves, the other thing you must do at the Ásmundarsafn is go up into the dome and sing. The acoustics are sublime and it has become a tradition when you visit the museum to go up and test them out. When I arrived, a group of schoolchildren were in the dome singing songs that echoed throughout the museum.

I didn’t visit all three museums in a single day, and I don’t recommend it either. It’s not that you couldn’t find the time to squeeze them all in, but personally my mind needs time and space to process the art and let it all soak in. One thought that is still bouncing my brain weeks later is this quote from Georg Guðni Hauksson in the Hafnarhús that perfectly sums up the Icelandic artistic mindset: