Togo’s history has not been a happy one. From the slave trade to European colonization to a familial regime that has run the country for the past 53 years and counting, the Togolese know all too well the meaning of the word, “struggle.” And yet, despite the political problems facing the nation today, Togo ranks as one of my favorite countries I’ve ever visited and I’ll destroy anyone who dares say an unkind word about the marvelous and generous people I met in Lomé. This post will act as an introduction to Lomé, Togolese history and the joy I experienced while getting to know this fascinating capital city.

Palais des Congrès/Assemblée Nationale Togolaise (Palace of Congress/National Assembly of Togo)

Architecture lovers rejoice! The Palais des Congrès in Lomé is a modern architectural wonder to behold. The concave building was completed in 1975 and became the new home for Togo’s National Assembly shortly thereafter. This marked the first stop on my journey through Togo’s capital and I was happy to learn that I could take as many pictures as I wanted, which was a nice change of pace from Ghana’s strict rules about photographing government buildings.

Aside from admiring the stunning architecture, the other reason visiting the Palais des Congrès jumped to the top of my list was because it also houses the National of Museum of Togo and, like Ghana before it, I was badly in need of a history primer before I could continue my exploration of Lomé.

The armed guards who so kindly let me take all my photos suddenly snapped to attention when this confident New Yorker started to take strides towards the front doors of the Palais des Congrès. “What are you doing?” they asked me in French. Now nervous, I responded, “Je veux visiter le Musée National.” They relaxed, let out a laugh and began quickly speaking in French to one another. I knew they were going to have some fun with me as I clearly I had stepped into something. It turns out the National Museum is located in the Palais des Congrès, but it is located at the back entrance and not the front. Basically, I attempted to walk through the super high security entrance reserved for National Assembly members and the President of Togo! Oops!

“You must follow the sign,” the guards said to me, still laughing. “Mais, il n’y a pas de signe,” I mustered in the bravest French I could squeak out.

Oh this sign! Oops again.

I really should take some responsibility for this mistake, but I’m going to trot out my trusty scapegoat, Lonely Planet, and place the blame squarely on their shoulders. You see, their section on Lomé is so incompetent and incomplete that they don’t list the National Museum as a place of interest in the guidebook. In fact, they don’t even mention it at all! Not only should it be denoted as a top attraction, but a warning that you must enter from the rear of the building would have been most helpful. Allow me to correct Lonely Planet’s error in judgment!

Musée National (National Museum)

For being such a skinny little slip of a country (the coastline is only 56km[35mi] long), Togo certainly has an abundance of ethnic diversity. In fact, there are about 40 different ethnic groups contained within its borders, making it one of the most multi-cultural countries in all of Africa. The three most prominent groups are the Ewe and Mina in the south and the Kabye in the north; the Ewe make up nearly one third of the population, far out numbering any other group.

The National Museum spends considerable time exploring the ethnography of these various groups with displays on traditional housing, clothing, religious ceremonies and musical instruments. As a great lover of music, I particularly liked see the various drums, woodwind flutes and xylophones-bell hybrids.

There were many items related to the various monarchies that once ruled portions of Togo, but my favorite was this hand-carved throne with two lions for arms and elephants for legs. Vodun, otherwise known as voodoo by people in the United States, is a native religion of Togo and Benin and still plays a pivotal roll in local culture. Vodun is the Ewe word for spirit; these spirits are divine beings that govern the Earth and protect its people. The spirits can be in trees, rocks and, of course, animals. The sacred animals on the throne were placed there to help protect the king and give him wisdom when ruling his people.

From the 11th Century until the late 15th Century, which marked the arrival of the Portuguese, most of these groups co-existed peacefully in relative isolation. After establishing forts in Elmina (Ghana) and Ouidah (Benin), the Portuguese set their sights on bringing the slave trade to Togo. Due to Togo’s limited coastline, the Portuguese were unable to find a suitable location to build a fort. Instead, they set up a Maison des Esclaves (House of Slaves), where slaves were kept until they could be transported to either Elmina or Ouidah and then brought to the Americas. So many slaves were pulled out of Togo that it earned the nickname “The Slave Coast” from the Europeans.

After 200 years of being captured and sold, Africans could breathe a small sigh of relief as slavery began to be outlawed all across Europe. This may have put an end to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, but the next phase of European domination was soon to begin.

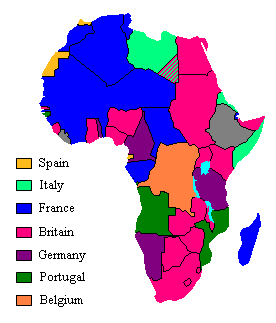

The Berlin Conference of 1884, otherwise known as the “Scramble for Africa,” saw the major European powers gather together to divide up the African continent amongst themselves, as if each nation was a Monopoly property ready to be bought and sold. Most African regions had multiple European nations with vested financial interests at stake and everyone (besides the actually Africans, that is) decided that it was best not to go to war over these territories, but rather to partition the continent off in a “gentlemanly” fashion.

Of course, all of this was done with a total disregard for the lives, cultures, local economies and futures of any African peoples. Instead of being sold as slaves in the Americas, Africans would remain in their homeland, and in turn become subjects to their colonial masters. They may have been paid a pittance for their labor, but it was feudal Europe all over again: the colonial powers took on the role of the King and the indigenous people acted as the serfs and peasants. The “scramble” lasted from 1884 until 1914 when the outbreak of World War I stopped all European politics dead in their tracks. Of note: the only two nations not to be colonized in Africa were Liberia and Ethiopia.

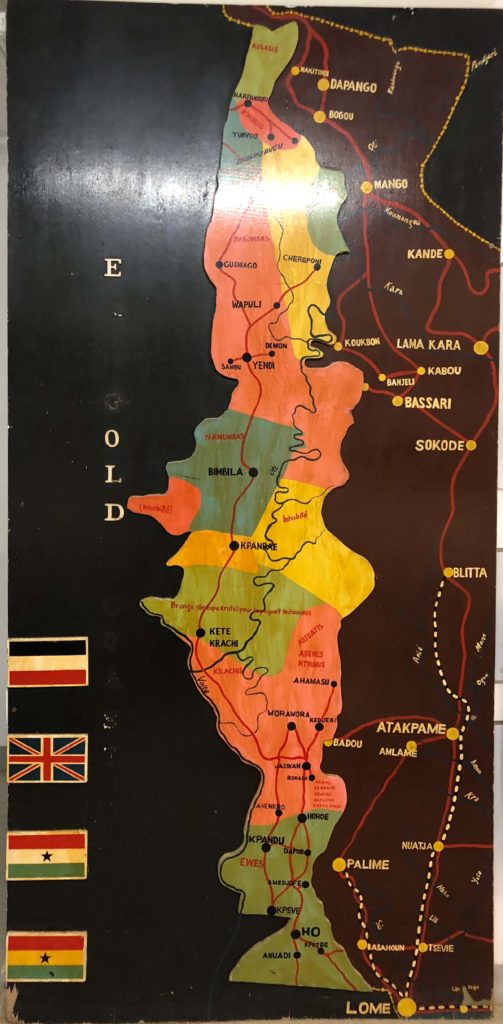

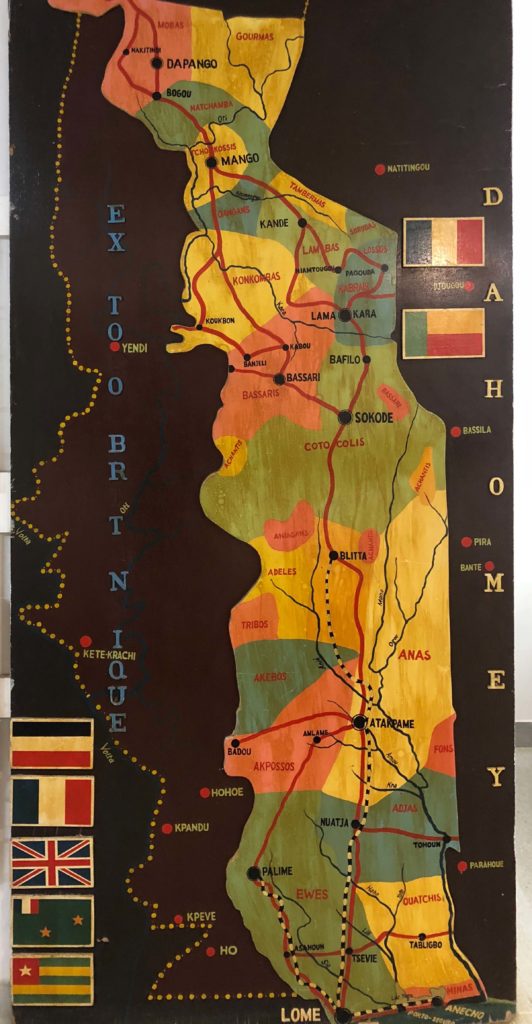

Slide the pieces of the above maps together and you’ll have Togoland, the colony that was given to Germany in 1884 and officially became Togoland in 1905. The Germans were cruel leaders, but they brought much modernization to the colony and especially to Lomé, establishing its port and building the first railway station and rail line that connected the main cities.

The British controlled The Gold Coast to Togoland’s west and the French governed to the east in Dahomey. When World War I broke out, the British and French invaded Togoland and quickly defeated the Germans. In 1922, the League of Nations, a pre-cursor to the United Nations, split Togoland in two, naming the western half British Togoland and the eastern half French Togoland. This had a devastating effect on the Ewe people, who heavily populated the entire Togoland coast. Suddenly families faced a new border between them, restricting travel and causing much cultural strife. By 1957, British Togoland voted to join the Gold Coast and two other British Crown Colonies to form the new nation of Ghana; to this day, the area of British Togoland, now called The Volta Region in Ghana, is populated with Ewe people and much trade and travel occurs between the Ewe on both sides of the border.

French Togoland remained a part of France until April 27, 1960, when the Republic of Togo received independence and was recognized by the United Nations. Togo’s first President, Sylvanus Olympia dissolved all political parties and declared himself president for life. He was killed in a military coup in 1963 and after several more transfers of powers, Gnassingbé Eyadéma took office in 1967, where he remained for 38 years until his death in 2005.

During the 1990s, the EU cut of all aid and relations with Togo, declaring the one-party country to be a dictatorship. Eyadéma entered talks with the EU and eventually relented to allow other political parties to exist in Togo, although no one from an opposing party ever won a single seat in Congress. Eyadéma also “won” election after election, even though there were widespread protests claiming fraud and corruption at the voting booth. In total, it is estimated that 15,000 Togolese dissidents were killed or disappeared during Eyadéma’s reign.

Eyadéma’s death in 2005 was sudden and the Togolese military quickly installed his son, Faure Gnassingbé as President. The global community, including many members of the African Union cried foul and Gnassingbé dutifully held an election, which he naturally won. This election in 2007 did carry a ray of democratic hope in the country: for the first time in history, members from rival political parties won seats in Congress. Today 32 out of 91 congressional seats are held by people of various parties outside of Gnassingbé’s.

Of course, Gnassingbé keeps winning election after election with no term limits in sight. There are negations with the AU to implement presidential term limits, but Gnassingbé insists they not be applied to him retroactively. There are protests during each election cycle, but my impression is that many Togolese are resigned to the fact that this is how things operate in their country. As long as Gnassingbé has the support of the military, it is unlikely that he will go anywhere anytime soon.

Togo is a peaceful country and as a tourist these political machinations will have little bearing on your visit. The citizens are also free to live their own lives, but if someone wants to better themselves by opening a business or expanding their property, the bureaucratic process is long and slow, fraught with corruption and requiring connections to push your applications along.

I had my own brush with government corruption when entering Togo. American citizens are eligible to get a visa on arrival at the Togolese border. You simply need to have a few papers in order (where you’re staying, the reason for your visit) and have proof of your yellow fever vaccine. Richmond had driven me to the Ghanaian/Togolese border at Aflao and was able to accompany me to the immigration window. I knew the cost of the visa was 15,000cfa ($27US) and was prepared with the cash. (Richmond had helped a British tourist make the same crossing a week prior and verified that this tourist was charged 15,000cfa.)

After I handed my passport to the two officiers, they looked it over and told me that Americans had to pay an extra 10,000cfa to enter Togo. I knew this was a lie, but Richmond urged me not to argue and to comply. I reluctantly paid the 25,000cfa, although you can clearly see from the receipts on my stamped visa that I was only officially charged 15,000cfa. The officiers returned my yellow fever card, but held onto my passport. Perhaps emboldened, they told me there was also a New Year’s tax and I would need to pay that before they could return my passport. I flatly refused and asked to speak with a supervisor. They quickly told me there had been a misunderstanding and there was no tax. My passport was returned and I entered Togo.

Monument de l’indépendance (Independence Monument)

In the roundabout outside the Palais des Congrès, you can find the Independence Monument, built in honor of Togo’s 1960 victory of achieving freedom from their colonial rulers. The gates to the monument’s plaza are often locked, but you’re free to walk around the enclosure and take pictures of the striking monument.

Place des Martyrs (Martyrs’ Square)

A few blocks from the Independence Monument is Martyrs’ Square, which is dedicated to the men and women who died fighting the French for independence. As Kwame Nkrumah was securing freedom for Ghana in 1957, riots were breaking out next door in Togo against French colonial rule. On June 21, 1957, protestors gathered to demand independence for French Togoland. The colonial army fired into the crowd, killing and injuring many Togolese. Although it took three more years before France released Togo from its grip, this was the bell that could not be unrung. Every June 21st, a wreath laying ceremony is held at the square to commemorate those who died that day. At night, the monument is lit like a Christmas Tree and is one of the most beautiful sights in all of Lomé.

Igor

Of course, none of the modern history I just relayed about Gnassingbé Eyadéma and his son can be found at the National Museum. You have to discover that for yourself by reading newspaper articles and bits of Togolese history online. Although this knowledge brings with it a bit of unease, it is the wonderful kindness of the Togolese people that mollify any political misgivings I have about Togo.

One morning at breakfast, I mentioned that I planned on walking down to the beach that stretches along Lome’s entire coastline. Igor, the amazing chef who prepared my breakfasts (and a few dinners) each day volunteered to join me, and thus began one of the truest friendships I have ever known during my travels.

The beach and the mighty waves breaking against the shore make for a nice metaphor about the slow process of political change in Togo. The waves are a constant, but they continually are reworking the sand and shells they come in contact with. The Togolese National Assembly has slowly evolved from a one-party entity to a government body comprised of members from six political parties and eighteen independents. Faure Gnassingbé, for what it’s worth, also appears to have opened up the country more than his father ever did. But it is the fortitude of the Togolese people that gives me true hope for this country.

Knowing Igor has brought so much joy to my life. Not only is he kind and wise beyond his years, but he has taught me so much about life in Lomé, the beautiful city he calls home. My French has greatly improved after messaging with him daily for over a year (along with Edem and Robert in Benin) and his English in turn has been honed to near perfection. I count him as family and will continue to hope for a better tomorrow for his sake and every other kind soul I crossed paths with while in Togo.

I usually tell people I’m not a “beach person,” and yet one of my happiest memories is spending that morning walking up and down the Lomé beach with Igor. Like Richmond before him, I don’t have much in common with Igor on paper and yet if you ask me now, I would easily tell you that we are very much alike. Meeting Igor not only gives me hope for Togo, but hope for the entire world. The new generation will not be like the others that have come before. We are a global community, creating bonds all over the planet. Through travel, imagine if every person befriended just one other person in each city, town or country he or she visited. The world would be interconnected on a personal level in no time. Globalization has connected our world in economic and political ways, but I’m talking about a more human connection.

Sometimes on a message board or in a Facebook group, after I proudly announce that I love Togo, I receive a response like, “How can you love a country that has only had two presidents in the past 50+ years?” (Before we start throwing stones at other countries, we should take stock of what a total shit show the US government has been of late and how Donald Trump is the single most incompetent leader in our nation’s history.) My reply is somewhere along the lines that, yes, Togo may have some political areas that need improvements, but when I say I love Togo I mean I love Lomé, the culture, the art, the food and especially the people.