While there are many small art museums and galleries scattered across Amsterdam, the four heavyweights sit within spitting distance from one another at Museumplein (Museum Square). Along with the Koninklijk Concertgebouw (Royal Concert Hall), the lovely public green space known as Museumplein is bordered by the Rijksmuseum (National Museum), the Van Gogh Museum, the Stedelijk Museum and the Moco Museum. You could spend several full days exploring the halls of these museums and still only see a fraction of each collection, and unless you’re an art obsessive (like me), devoting some meaningful time to one or two of the museums rather than racing through all four might be a more effective use of your energy.

What does each museum have to offer and which one is the best fit for you? In this post, I will give you the rundown on each institution and the pros and cons that come with each visit. The Rijksmuseum and Van Gogh Museum are the more popular of the four by a mile, but does that make them better? (Spoiler Alert: It does not!) Personal taste and interest levels will, of course, vary, but without further ado, let’s dive in and get to know contestant number one.

The Rijksmuseum

Rijksmuseum literally translates to “National Museum,” and true to its name, it chronicles the history of Dutch painting from 1100 to 2000. The museum was founded in 1798 in The Hague as a way for the Dutch to compete with the Louvre in Paris. The foundation eventually moved to Amsterdam where it was housed in the Koninklijk Paleis (Royal Palace) until it found its way to its current home, built expressly for the purpose of accommodating the growing collection, in 1885.

Since the early 2000s, the Rijksmuseum and the Van Gogh Museum have traded owning the title of “most-visited museum in The Netherlands,” each averaging approximately 2.5 million visitors in recent years. (In fact, both museums rank consistently in the top 25 visited museums in the world.) This only adds pressure for the traveler, vaunting these museums to “must-see” status; to pass them by would somehow be unforgivable. Like some bad after-school-special on the dangers of peer pressure, the Rijksmuseum is waiting for you with a cigarette and six-pack of beer saying, “Hey, everyone else is doing it.” No one likes to feel left out, and suddenly you find yourself carving out time from your schedule to see the Rembrandts and Vermeers, whether you had any organic interest in them or not.

If the original goal of the Rijksmuseum was to rival the Louvre, it was going to need a “Mona Lisa” in its collection to rope in the crowds. Enter “De Nachtwacht” (The Night Watch), Rembrandt’s 1642 epic painting that acts as the centerpiece of the museum’s Gallery of Honor. When the museum opened, I witnessed entire tour groups literally sprint to the hall so they could be first in line to snap a photo of the famous painting. Upon visiting Amsterdam, there are a few IG requirements for any tourist hoping to reach the pinnacle of basic: a shot of them looking out at the canals, one in a cafe smoking a joint to show they’re cool and lastly one in front of “The Night Watch” to prove they’re cultured and smart too. Rembrandt has become just another item to check off the list.

Sadly, the museum itself feeds into this bad behavior. Upon entry, you are handed a map of the Rijksmuseum with a dozen marked “highlights” on each floor. People treat this like a treasure hunt, racing from room to room, making sure to snap a pic of each famous painting without absorbing any of it. As for the works of art not deemed “highlight-worthy?” Forget about it! That’s why there are millions of photos of “The Girl in Blue Dress,” “ Landscape with Waterfall,” and “The Milkmaid,” floating around out there on social media. Like sheep, visitors take photos of what they are told is important and move on. When viewing art, you need to figure out what moves and inspires you. It’s a very personal thing and can’t be dictated by anyone else. It’s obvious why art museums get a bad reputation for being “boring;” when you’re told what should invoke awe and wonder and then find it to have the opposite effect, how can you not feel like you’re not “getting it?” If you take the sense of discovery out of the equation, it will only lead to disappointment.

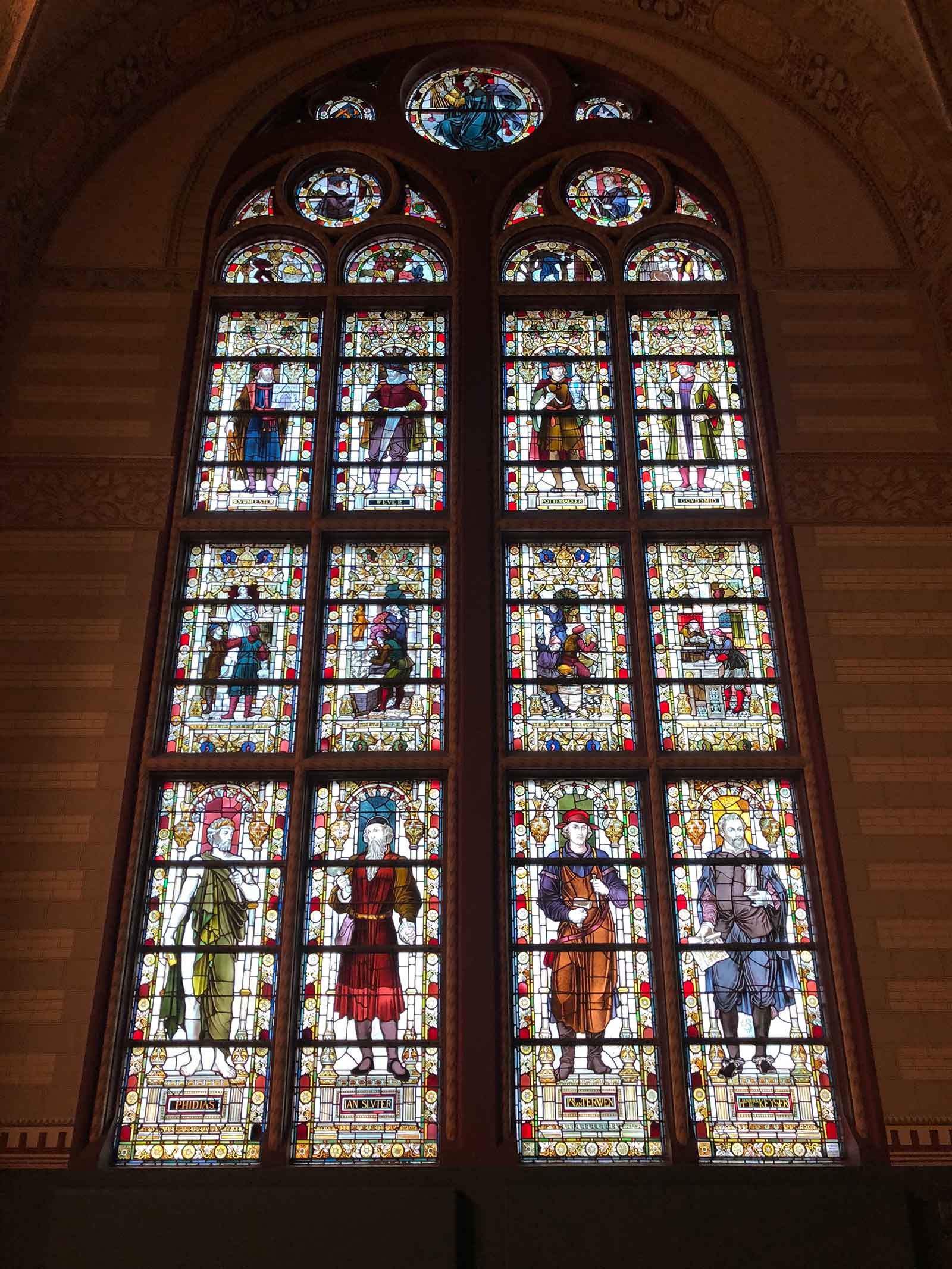

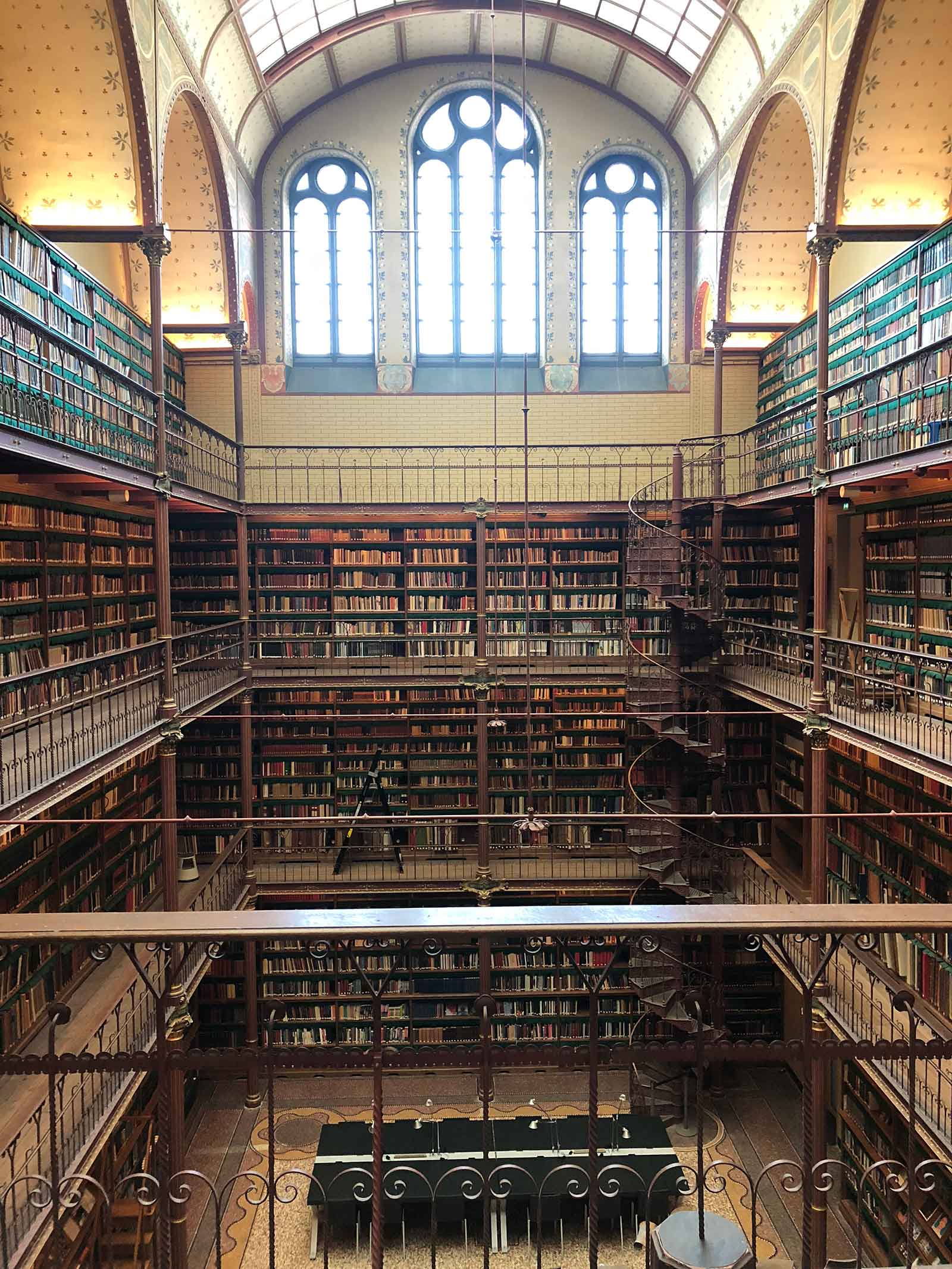

What doesn’t disappoint in the Rijksmuseum is the building itself. I don’t know if it’s quite worth the 20€ entry fee just to see the interior architecture (19€ if you book your ticket ahead of time online), but it certainly helps mollify the expense when you’re surrounded by such splendor. The museum has undergone several rounds of renovations over the years and it really has been kept in immaculate condition. At times, the atria with stained-glass windows almost make you feel like you’ve wandered into a cathedral rather than a museum. The library, as well, is just as impressive as any of the rooms of Dutch paintings.

While others rushed to the Vermeers, I scurried up to top floor where the art created from 1950-2000 was on display. Suddenly, it was as if I had the entire Rijksmuseum to myself. The throngs of selfie-stick wielding tourists garner zero cachet on social media posing with post-modernist art; there’s a reason this era is hidden away in the attic and not down in the “Gallery of Honor!” It’s no surprise to anyone who has been reading my posts, that this was my favorite floor in the museum.

Two exhibits were of particular interest to me. The first was a series of Nazi propaganda posters that were created to entice the Dutch into enlisting in the Nazi army. These were the equivalent of the United States’ Uncle Sam posters encouraging young men to join the armed forces. What’s interesting about the posters is that the text was in Dutch and not German. The Nazis tried to play a long game, hoping to slowly fold the Dutch into their newly-forming empire. The Soviet Union imposed the Russian language almost instantly on their captured nations, but the Nazis attempted to appeal to their occupied peoples in their own languages. The goal was for people not to realize how powerless they were until it was too late.

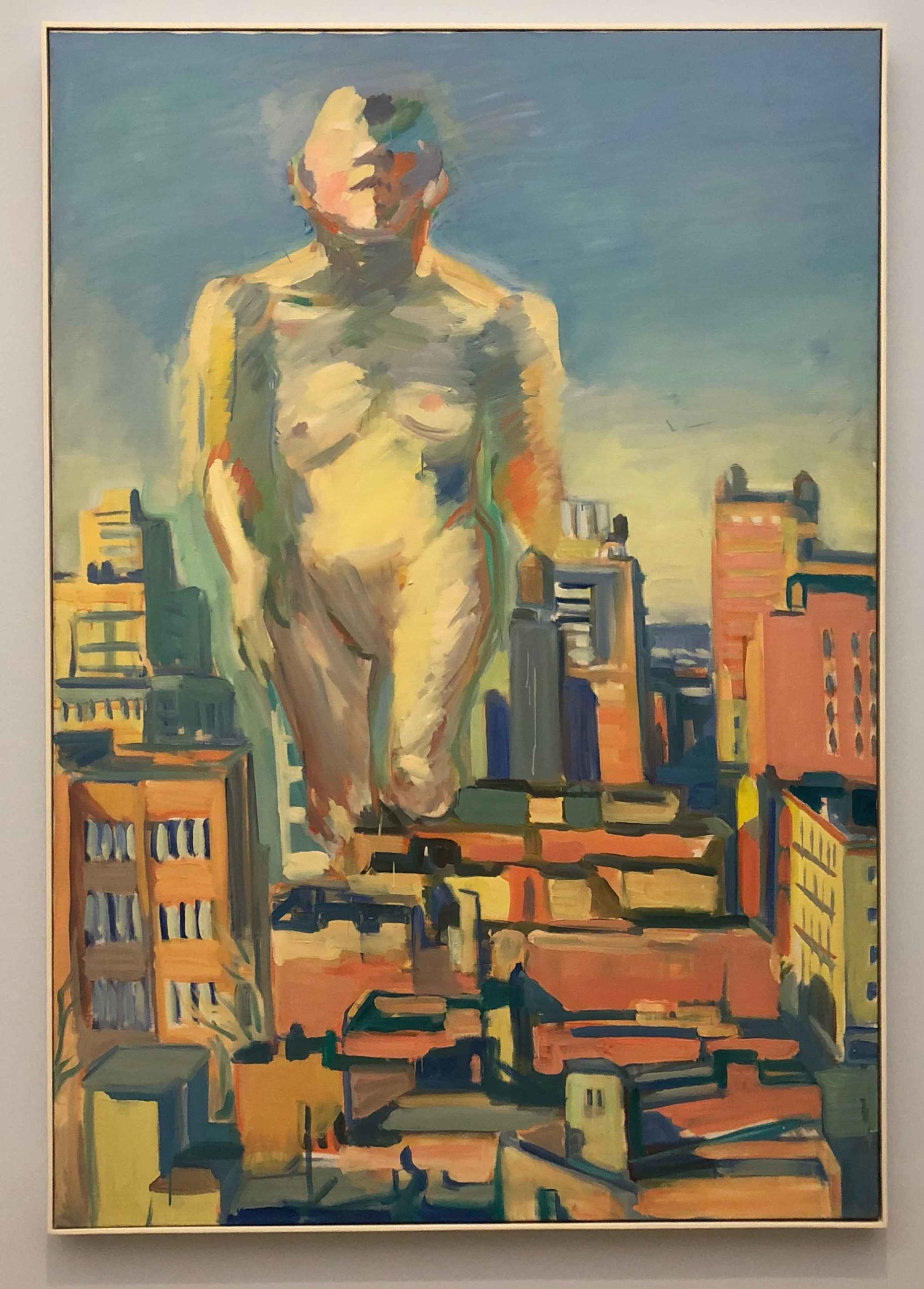

Even better was the exhibit detailing the expansion of Amsterdam in the 1970s, a time when the capital went through a period of urban sprawl and suburban apartment complexes sprang up around the edges of the city. Amsterdam’s layout is both a brilliance in urban planning and a confining area of canals and waterways that restrict any sort of growth. Much Strum and Drang surrounded the growing pains of the Dutch capital during the 1960s and 70s. It became a balancing act of remaining environmentally-friendly, aesthetically-pleasing and still providing a functioning city for the burgeoning population. Modern buildings lacked the charm of the row houses from the Dutch Golden Age and their geographic placement kept the working classes from living directly in the city they served. The poster above may not have the technical detail of a Rembrandt or Vermeer, but its revelations of modern Dutch life are far more interesting (to me) than anything found in “The Night Watch.”

And that leads me to my biggest complaint about these old Dutch masters. Yes, their technique is exquisite: I observed lace collars and gold trim on canvas that looked as realistic as a photograph. But their subjects did absolutely nothing for me. Random and forgotten members of the ruling class; bucolic landscapes; still life platters of fruit and wild game- what interest do these hold for the modern viewer? What emotions do they evoke? What political/social statements do they make that are still relevant to today? I can appreciate the painting on an intellectual level, but they don’t set my heart a flutter. I need a little more bite for my buck.

The Stedelijk Museum

Next door at The Stedelijk Museum, the entryway boldly promises that you will “Meet the Icons of Modern Art.” You won’t find any stuffy Golden-Age paintings here, nor will you be vying with the crowds aping swarms of locusts at the Van Gogh and Rijksmuseum to catch a glimpse of the art. Despite its place on the Museumplein, the Stedelijk sees less than a quarter of the annual visitors that the Rijksmuseum receives. Yes, the exhibits may be labeled as “weird” which often translates to “inaccessible,” but I find it be just the opposite. Realistic oil paintings have been swapped out for experimental sculptures, but the subject matter is fresh and deals with issues currently affecting our world: women’s rights, gay rights, destruction of the environment, nuclear war, personal identity and more.

The Stedelijk Museum was founded in 1895 and has the largest collection of modern and contemporary art in The Netherlands. During World War II, museum workers stashed the collection in a bunker out in the Dutch countryside, where they took turns keeping watch to make sure the Nazis didn’t abscond with (or destroy) their art. In the 1960s, the Stedelijk began amassing video art and the medium has become an integral part their exhibition experience.

I visited during the 100-year anniversary of women gaining the right to vote in The Netherlands, and to commemorate the occasion, the Stedelijk was devoting much of their exhibition space to female artists. There was also a “Hybrid Sculpture” exhibit that placed real-world objects in an artistic context, as well as a video series from Barbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burcu that captured the art of fan dancing in the transgender community of Northeastern Brazil.

Not only are these pieces dealing with current, real-world issues, but the Stedelijk is also much easier to visit from a logistical standpoint too. If you don’t book your tickets online months in advance to the Van Gogh and Rijksmuseum, you’ll be doomed to stand in line outside for hours with the hopes of getting into the museums. Not so at the Stedelijk, where I simply waltzed up to the counter, purchased my ticket and was granted immediate entrance. Sometimes it’s impossible to plan your future travel with such certainity and if you find yourself with a few free hours in Amsterdam, they could be better spent in the Stedelijk rather than waiting for the opportunity to see the Rembrandts next door.

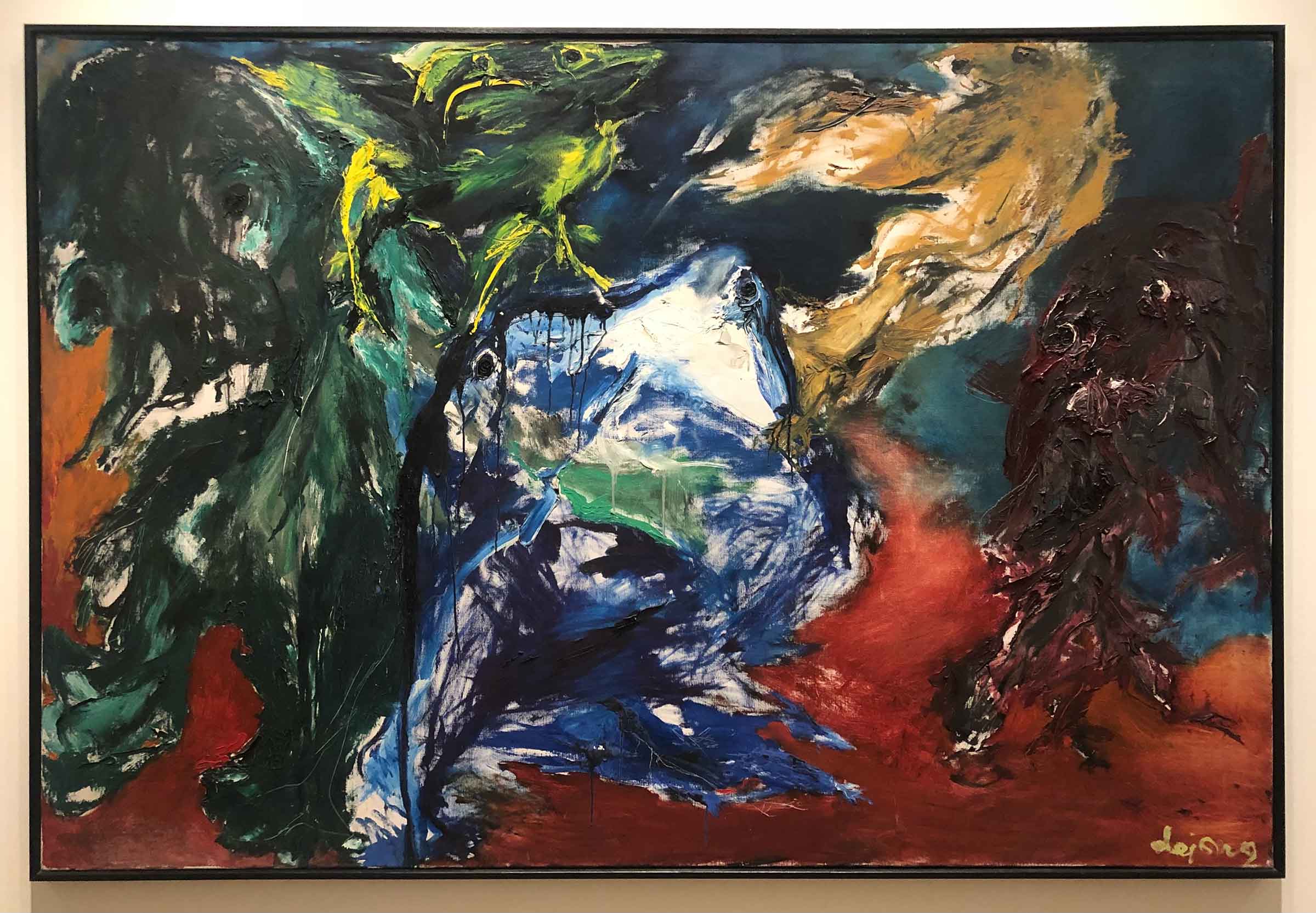

The Stedelijk has a wonderful array of the paintings and sculptures from the avant-garde Dutch artist, Karel Appel. Appel was one of the founding members of the CoBrA movement in the late 1940s, that brought together artists from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam. They believed the process of creating art was just as important (if not more important) than the finished product itself. Bright colors, aggressive lines and figures that could simultaneously evoke both horror and humor were essential components of the movement. Appel railed against the “civilized art” on display in the Rijksmuseum, wanting to instead create art that bridged the gap between the conscious and unconscious mind. Initially, CoBrA‘s exhibitions were met with disdain by critics and the public alike. Appel found success in Paris, New York, Belgrade, Italy and Brazil before finally receiving his due in Amsterdam in the 1990s.

The permanent collection or the “Base Collection” at the Stedelijk is housed in- you guessed it- the basement of the museum. The layout is described as a “quasi-urban environment” that situates the pieces almost as if they were street art in a labyrinth-like setting. Of course, what you see above is just a tad bit more arresting than the windows at Bergdorf Goodman on Fifth Avenue! From a piece of pop art by Andy Warhol, to a Dutch iconoclast, the Base Collection attempts to elicit sharper emotions than those derived from “The Milkmaid” at the Rijksmuseum.

It was on my way to the Stedelijk that I met a French student, Sam, who was in Amsterdam on a weekend holiday. Like me, he was traveling solo and we hit it off right away. We spent hours ambling through in the Stedelijk and it was really rewarding discussing the collection with him. He often brought new and different insights to the art and for the remaining 36 hours that he was in the city, we became inseparable, all thanks to our bonding session at the museum. This is a paradox of solo travel: I would never have been open to meeting Sam if I hadn’t traveled to Amsterdam by myself, but at the same time, I wouldn’t have enjoyed the Stedelijk half as much if I didn’t have Sam there to discuss it with. I also don’t think our conversations would have been nearly as interesting by half had we been discussing the works at the Rijksmuseum rather than the Stedelijk. These crazy, abstract pieces truly allowed us to have a meeting of the minds and bridge our cultural differences through these universal themes.

Van Gogh Museum

The Van Gogh Museum opened in 1973 and it contains the largest collection of Van Gogh memorabilia (200 paintings, 400 drawings and 700 letters) in the world. It is the only one of the four art museums on the square that does not allow any photography inside. Still, this didn’t stop people from brazenly taking photos and having guards confiscate cameras in order to delete the pictures immediately after.

Because of its popularity, you must buy your ticket to the museum ahead of time. I lucked out with my Rijksmuseum booking and was able to snag an early entry to the museum. Fortune did not smile on me at the Van Gogh, where all the morning slots were full for each of the five days I was to spend in Amsterdam, saddling me with a slot at 14:15. You only have 30 minutes after your scheduled time to enter the museum, after which your ticket becomes invalid with no refunds given. This actually makes for a somewhat stressful situation and you end up planning your whole day around the museum visit. Sure, you can do something in the morning, but you can’t risk straying too far from the area and gamble not returning in time. I even found it difficult to relax and enjoy my lunch, as I was constantly checking my phone lest I lost myself in Amsterdam’s atmosphere and zoned out before 14:15. I enjoyed the Van Gogh exhibitions, but visiting certainly came at a cost.

Because this museum focuses on just one artist (although a few of his contemporaries are given some space in the collection as well), the curators can take you on a journey from Van Gogh’s birth in 1853 to his tragic death in 1890. The artist’s letters, many of which were addressed to his brother Theo, provide great insight into his work and private life. Van Gogh suffered from depression, loneliness and mental illness, ultimately succumbing to his demons and dying at his own hand with a gunshot to the chest. He notoriously cut off his own ear, although not to give to a lover as is often misstated, but rather in a fit of mania and rage after a bitter debate over art with Gauguin. If I’m being honest, I found the letters and saga of his descent into madness far more moving than the artwork, even though it was exciting to see such world-renowned works as “Sunflowers,” “Yellow House” and “The Potato Eaters” in person.

Moco Museum

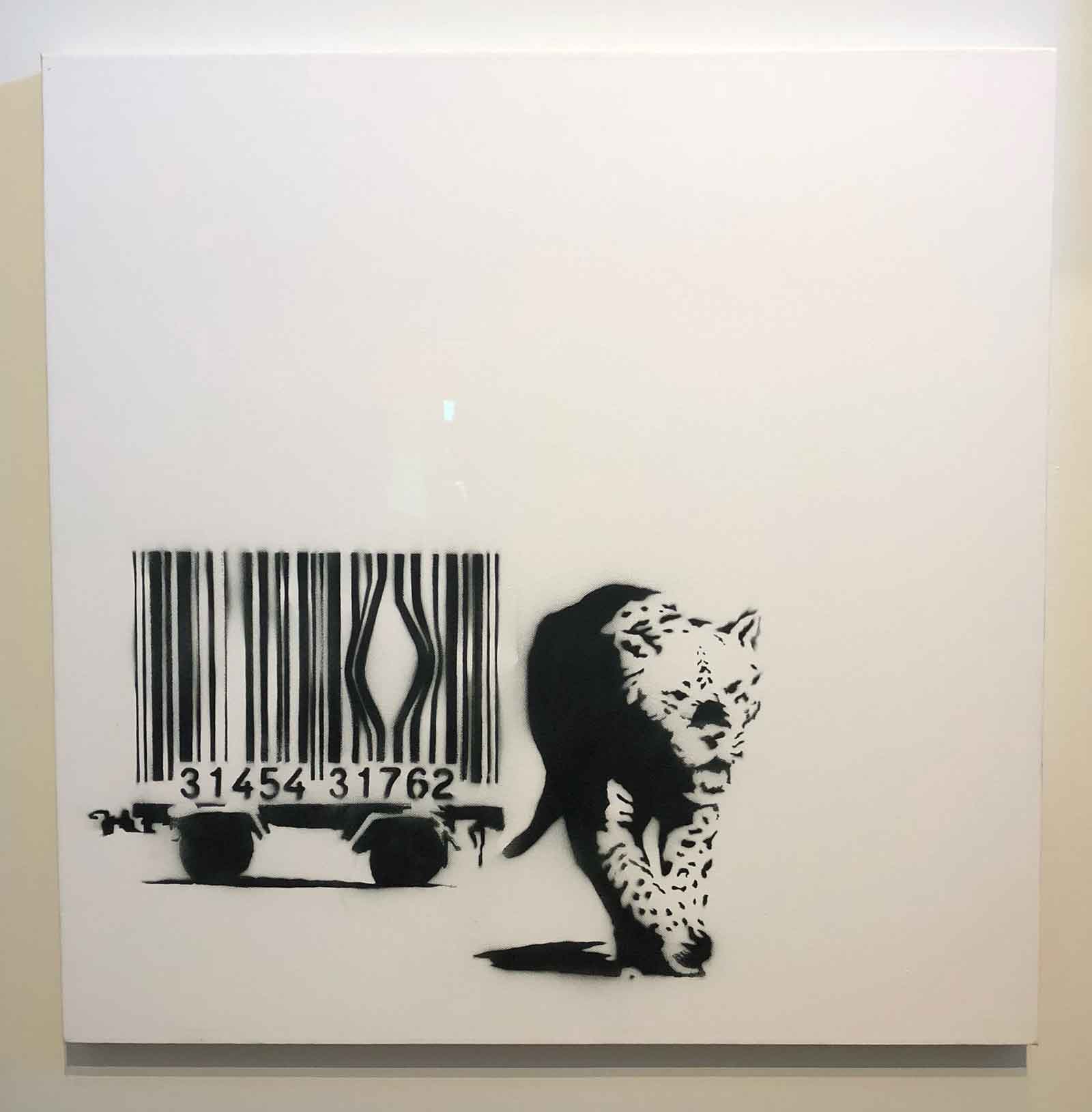

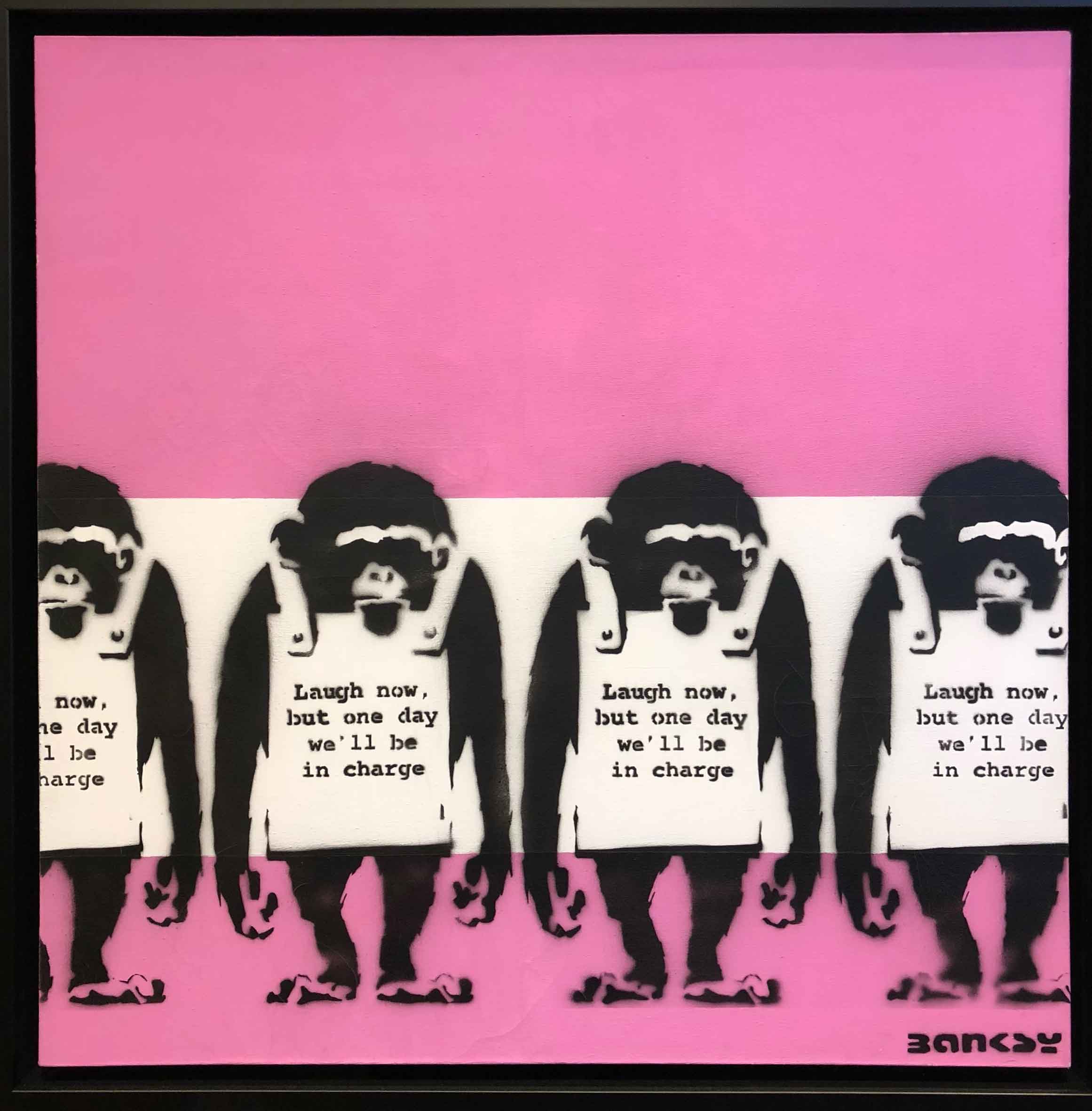

Always save the best for last, right? Museumplein’ s latest addition, Moco (Modern Contemporary) Museum opened in 2016, finding a home in the Villa Alsberg, which was built in 1904 for a wealthy family when the square was still considered a residential neighborhood. If you only have time for one art museum in Amsterdam, Moco should be it. I went gaga for all the exhibitions, but especially loved Bansky’s anti-war, anti-capitalist, anti-consumerism art.

No one knows exactly who Bansky is, even though he has been making waves in the art world for decades. When Bansky was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short in 2011, people speculated that he might reveal himself to the public if he won the Oscar. Alas, Bansky neither attended the ceremony nor took home the statue and while many have attempted to guess his identity, no one has ever been able to confirm exactly who he is.

What we do know is that Bansky began creating street art in the UK under his pseudonym in the 1990s. At first he created images with freehand spray paint, but soon found that he couldn’t complete a project in a single night without interruption. This prompted him to create massive stencils in a studio space which he would carry to the wall he wanted to paint, allowing him to quickly spray paint over the stencil and leave only the image behind. Bansky has made his presence felt all over the world from LA to New York to South Africa to South East Asia and all over Europe. He has spray painted on the sides of hospitals, prisons, private homes, banks and department stores. Bansky infamously painted a boy with a paint can and the caption “I remember when all this was trees,” on the side of a condemned Packard plant in Detroit, Michigan in 2010. Two men rescued the 7’x8’ slab of concrete wall before the plant was demolished and sold it at auction for over $100,000.

Bansky’s works offer scathing attacks on consumer culture, police brutality and the effects of war on families and children. His art vacillates between laugh-out-loud funny and thought-provoking, and witty and moving. Hope is never lost in Bansky’s art either; grenades are replaced with flowers and cops in full riot gear are bedecked with smiley faces. Even at our worst, Bansky has quite given up on humanity yet.

If Bansky is a mystery man, how are his paintings on display in a museum and being sold at auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars? He created a group called “Pest Control,” the members of which know his identity and act as his agents with museum curators and private collectors. All sales are processed through this shell corporation, allowing him to retain his anonymity. In addition to his art and the aforementioned documentary short film, Bansky has published several books of art criticism and poetry.

One of Bansky’s more notorious acts was stenciling on the barrier between Israel and the West Bank. Bansky is always trying to tear down the walls in our society while ironically literally needing the walls to act as his canvases around the world.

Encircling the former villa is a sculpture garden of playful contemporary pieces. Bansky’s 3D pieces often take on a surrealist quality; they manage to make you chuckle, all the while delivering a clear message like a dart to a bullseye. One thing I greatly admire about modern and contemporary art is that they allow for greater senses of irony and humor than Baroque, Renaissance and other pre-20th Century periods. Bansky has a fantastic quote that is trumpeted throughout Moco: Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable. Once you start looking at art through this lens, it’s difficult to not judge the Rembrandts and Vermeers as lacking omph. There’s nothing disturbing or threatening about those pieces to the status quo. Some may have made waves at the time, but for today’s audience, this is art that comforts the comfortable. It’s easy to digest and just as easy to pass through the other end. The images don’t linger or call you to any action. They are pretty paintings and nothing more. Bansky’s work speaks to the modern viewer, attempting to both rock the boat and shake the viewer awake. My eyes are wide open.