The woman slowly leaned back in her chair, took out another cigarette and exhaled a mighty plume of smoke before repeating what she said thirty seconds earlier: You no go Skopje.

Maybe something was being lost in translation.

I had made my way down to the Tirana international bus station, and by bus station I mean parking lot behind a strip mall where all buses bound for foreign destinations congregate, to search for a company that would sell me a ticket to Skopje for the following day. (In the Balkans there’s no need to purchase a bus ticket more than one day in advance.) Along the back wall of the strip mall various booths had been set up, each one housing a different bus company that controls the transportation between Tirana and its European destination. This booth sells tickets to Belgrade; this one to Vienna; down here you can go to Istanbul and over there to Budapest.

I thought I was at the right booth for Skopje, but perhaps I was mistaken. Finally, another man explained that there had been some sort of rock slide, making it impossible to travel on the highway between Tirana and Skopje. But I had reservations at а hostel in the North Macedonian capital for the following evening! What was I going to do?

My chain-smoking bus operator explained that all buses were being routed to Kosovo’s capital of Prishtina. From there I could purchase an onward ticket to Skopje. (I’ve taken the bus from Skopje to Prishtina before. A bus departs every hour in both directions and the journey takes about two hours. The ride from Tirana to Prishtina would last four hours; I booked the earliest departure at 6:00 and now would plan for an unexpected pit stop in Prishtina for the next day.)

Obviously, the moral of this story is that you need to roll with the punches when traveling. The best laid plans are often just waiting for that proverbial wrench and what other choice did I have but to make the most of the situation in which I had found myself.

Entering Kosovo

In the biggest plot twist of all, my bus to Prishtina actually left Tirana on time! Perhaps the first Balkan bus to ever do so in the history of Balkan buses! I was on my way and excited to revisit this capital I had so enjoyed during my first Balkan adventure a year earlier. When we reached the border, I was the only passenger who had to have my passport stamped by border control; Albanians and Kosovars can travel between their two countries with a mere standard issue ID card.

The border control officers entered the bus and took my passport. All eyes were on me. “An American, eh?” He leafed through each page, pondering the menagerie of stamps I had already collected. Suddenly he stopped and smiled. “So you have been to our country before I see.” “Yes, I loved Kosovo very much,” I replied. “Yes, I can see you can’t keep away!” My bus mates who understood English all laughed, the guard stamped my passport, and we were off to complete the trek to Prishtina.

The first thing I did at the bus station- yes a real bus station this time- was to go to the counter and purchase my ticket to Skopje. My departure time was 18:00, giving me a full eight hours in Prishtina. I was determined to make the most of it.

Katedralja Nëna Terezë (Cathedral of Mother Teresa)

The Cathedral of Mother Teresa, whose namesake, although born in Skopje, was ethnically Albanian, is a recent addition to the Prishtina skyline. The cornerstone was laid in 2005 by then-President of Kosovo Ibrahim Rugova. This carried a large symbolic weight as Rugova was a Muslim and both religious and ethnic tensions were still running high after the Kosovo War which lasted from 1998-99. Rugova, who was known as the “Gandhi of the Balkans,” died in office in 2006 without seeing the project completed.

It took Atifete Jahjaga, the first female President of Kosovo, who served from 2011-16, to finish what Rugova had started. Jahjaga held several inter-faith meetings, bringing together leadership from the Muslim, Catholic, Jewish and Serbian-Orthodox communities. She worked tirelessly to unite the various groups living in Kosovo, as well as raise Kosovo’s status and integrate it within the rest of Europe; Kosovo’s admission into the EU is still pending at this date.

For only one euro, an elevator will whisk you to the top of the cathedral’s bell tower for the best 360-degree panorama of Prishtina. With this bird’s-eye view of the capital, you can easily map out anywhere you might need to go in the city. Although Prishtina has a fairly extensive public bus system, the city is immensely walkable and all major sights can be reached by foot.

Universiteti i Prishtinës (University of Prishtina)

The University of Prishtina has a sprawling campus that currently enrolls 42,000 students. Kosovo, even when it was a part of Yugoslavia, has always been a land with two official languages: Albanian and Serbian. When the university was established in 1969, classes were to be offered in both languages, but this raised objections from some members of the Socialist Party in Belgrade. They felt that teaching in Albanian would engender too much nationalistic pride and that the Albanian majority would develop separatist notions.

Josip Broz Tito, President-for-life of Yugoslavia, intervened and granted the university permission to operate in a bilingual fashion. Tito, for whatever faults he had, was always trying to inspire a feeling of kumbaya amongst the various ethnic groups of the former-Yugoslavia. He believed they were stronger together than apart, and in instances like this, keeping the peace was more important than inciting a full-scale rebellion of the Kosovar Albanians by forcing all lectures to be given in Serbian.

In 1999, at the end of the Kosovo War, the University did split in two. The main campus in Prishtina is run as an Albanian (and English)-speaking school; a new branch opened in Mitrovica, an ethnically Serbian city in northern Kosovo, that provides learning solely in Serbian. (My father, who worked for the Department of Education in the US, had to deal with a lot of bureaucracy, but it was nothing compared to this!)

Biblioteka Kombëtare e Kosovës (National Library of Kosovo)

Two of Prishtina’s biggest tourist attraction are located on the university’s campus. The first of which is the National Library, the capital’s most famous- and controversial- sight. Once declared the ugliest building in the world by a popular magazine, the National Library is certainly a structure unlike any other I’ve seen. Over the years it’s reputation has defiantly blossomed and for better or worse, it has become a symbol of the city.

Built in 1982, the entire library is encased in a metal netting and the roof is adorned with 99 white domes, meant to resemble the traditional hat worn by Kosovar men until the early 20th Century. The interior has intricately designed marble floors and various socialist brutalist accoutrements.

In 1989, with Tito long dead and Yugoslavia on the verge of collapse, the central government in Belgrade revoked Kosovo’s autonomous designation within the socialist republic. Albanian courses were forbidden at the university; Serbian forces occupied the library and destroyed over 100,000 Albanian-language books and historical documents.

As Serbia and Montenegro went to war with Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Kosovo (North Macedonia somehow wriggled out of this conflict without shedding a drop of blood), Kosovar Albanians took back the library and used it to house Croat and Bosnian refugees.

Today, the library is once again operational and open to both students and the greater public alike. During my research, I read that you needed to show your passport at the front desk before entering, but I wasn’t asked for ID either time I visited the library. This is one of the holy grails of socialist brutalist architecture and the staff is used to tourists wandering the halls and snapping photos. One worker even told me not to miss the mosaics leading up to the third floor! (Because Kosovo was essentially run by the UN between 1998 and 2008, English is widely spoken and understood by most Kosovars, whether they be of Albanian or Serbian heritage.)

Galeria Kombëtare e Arteve e Kosovës (Kosovo National Art Gallery)

Also on campus, and directly behind the National Library, is the Kosovo National Art Gallery. The gallery has the largest collection of contemporary Kosovar art in the world and is completely free to visit. On my second trip to the museum, the entire second floor had been given over to Mina & Leo, a romantically linked, though proudly unmarried couple, and two of the rising stars of the Kosovar art scene.

The theme of their exhibition was “Kurrë s’kan me u rrit” (“They’ll Never Grow Up”), a riff on the Picasso quote, “Every child is an artist. The problem is to remain an artist while you grow up.” Mina & Leo both seek to explore the culture, beliefs and socio-political-economic conflicts in post-war Kosovo. As the younger generation moves forward from the violence of the Yugoslav Wars, what future awaits them?

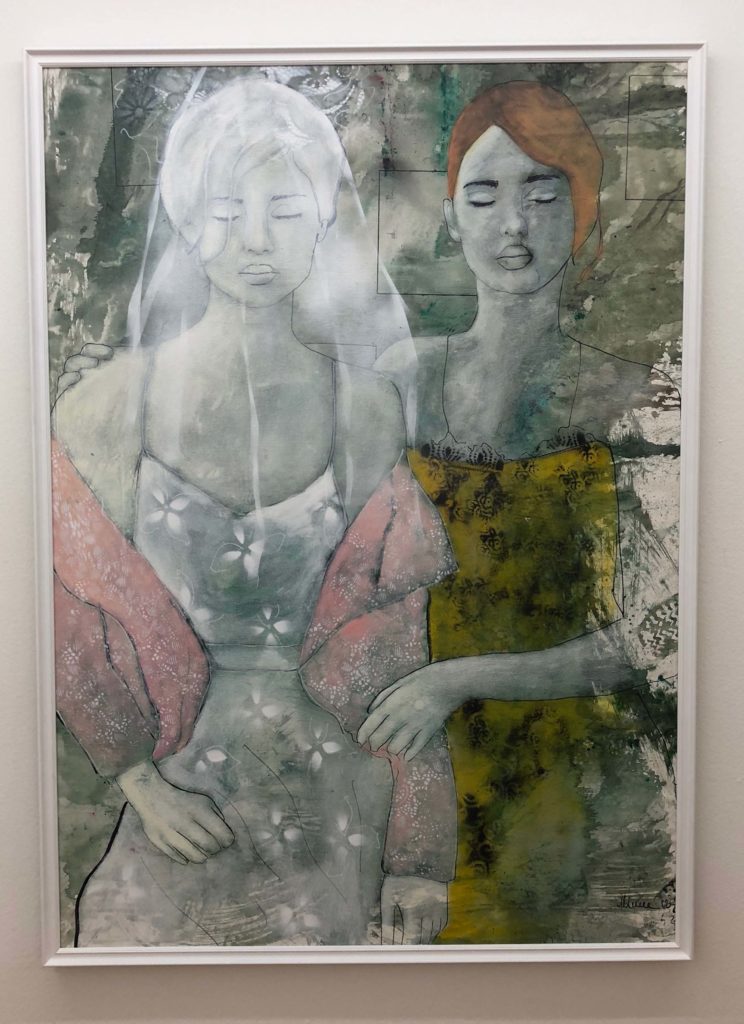

Mina/Brides

Mina’s contribution to “They’ll Never Grow Up” is a series of paintings called “Brides,” which examine Kosovar women on her wedding days. We see their bodies and faces, but the eyes in each painting remain shut. The brides are mediating- indeed, the paintings are instilled with a spiritual aura- dreaming of a new reality where they can coexist peacefully with their partners and break free from traditional roles, cycles of violence and domestic abuse.

The bride is a symbol for new beginnings (rebirth is a very common theme in Kosovo today). She is determined to take her fate in her own hands and create positive change in her life. Existing with her partner as an equal and overcoming road blocks to human and woman’s rights that have heretofore hindered Kosovar women are some of the themes Mina hopes to examine in these paintings. The institution of marriage doesn’t need to be abandoned, but it does need an overhaul. Kosovar women are dreaming of a better life and when they open their eyes, they wish to see their dreams manifested into reality.

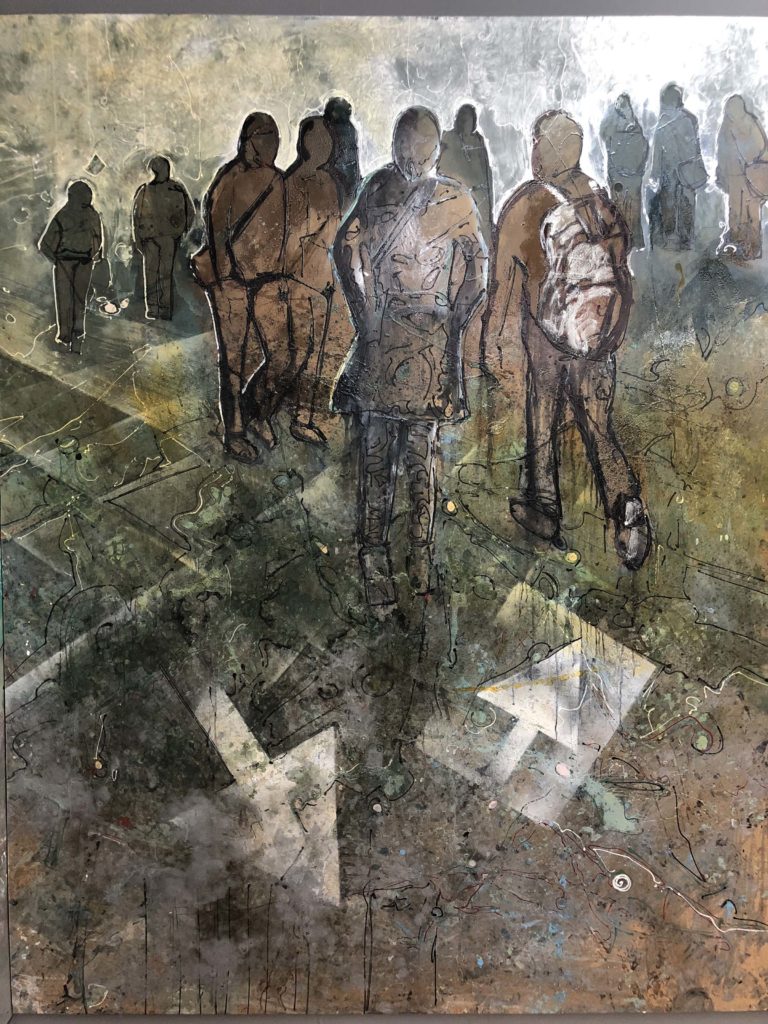

Leo/Walking Feet

Unlike Mina’s Brides, Leo doesn’t show us the of the faces on any of his figures. Leo’s paintings depict a world full of boundaries, rules, laws, traditions, crimes and economies that make us “robotized slaves” to our overlords. Our souls and humanity are in danger of being lost in the shuffle. His figures no longer want to be a part of this world; they are attempting to overcome its obstacles by walking, dancing, fighting and flying over the chaos.

The arrows on the ground point the figures along the paths of their personal histories. For Kosovars, this means emerging from the recent destruction of war. Still, Leo remains optimistic and hopeful that his fellow youth will overcome these difficulties. Just as Mina and Leo co-exist harmoniously in their personal lives, art imitates life with their two sets of paintings on the museum walls. Mina’s Brides, representing quiet strength and inner thought, happily compliment Leo’s Walking Feet, which depict the actions people are taking to create a better tomorrow.

NEWBORN Monument

The NEWBORN monument was unveiled on February 17, 2008, the day Kosovo declared independence, officially allowing the local administration to take the reins from the UN and fully govern the fledging nation. When the NEWBORN monument was first revealed, all the letters were painted in a bright yellow. Visitors and citizens were both encouraged to sign their names or write a message on the letters. Every February 17th, the letters receive a facelift and are presented in a new theme.

My second visit to Prishtina was in 2018, which marked the tenth anniversary of Kosovo’s independence. The occasion was commemorated by replacing the “B” with the number “10” in gold. The NEWBORN monument has become selfie central for any tourist in Prishtina.

Pallati i Rinisë dhe Sporteve (Palace of Youth & Sports)

Runner-up to the National Library in socialist brutalist awesomeness is the Palace of Youth & Sports, situated directly behind the NEWBORN monument. The facility was built in 1975 and originally called (at Tito’s behest) “Boro-Ramiz,” who were two socialist leaders, one Albanian and one Serbian. There was that Tito again, always attempting to create unity between Kosovo’s two main ethnic groups. (Today Kosovo is 88% Kosovar Albanian, 7% Kosovar Serbian and 5% other, which shows how far the population has tipped towards the Albanian majority.)

The structure has two arenas, a shopping mall, a movie theater and underground parking. The palace was badly damaged during the Kosovo War and the larger of the two arenas has not been used since 2000. Prishtina’s popular basketball team plays home games at the smaller arena and plans are underway to restore the 8,000 seat venue in next five years.

Bill Clinton Statue

How did the Kosovo War come to end in 1999? US President Bill Clinton pushed for NATO to bomb Belgrade in an attempt to cripple their government and end the decade-long war that had ravaged much of the former-Yugoslavia. This was a controversial call at the time and still doesn’t sit well with some Serbians today, but it was effective. Serbia withdrew its troops and the newly-independent Balkan nations could finally start to pick up the pieces. Of course, Clinton is regarded as a hero in Kosovo for recognizing Kosovar independence and facilitating the deployment of UN peacekeeping troops to enter the country and restore order. Clinton himself was at the unveiling of the statue in 2009 and made a speech heralding the bravery of the Kosovar people.

Muzeu Etnologjik (Ethnographic Museum)

I’ve spent much time discussing Kosovo’s modern history, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the nation’s Ottoman past. Yes, like all the other countries in the region, Kosovo was once part of the Ottoman Empire from the mid-15th Century until the 1910s. Prishtina’s Old Town still contains remnants of that time and the best place to start your exploration of Ottoman-era Prishtina is the Ethnographic Museum. (Entry is free, but donations are strongly encouraged.)

The museum occupies three houses on the former estate of Emin Gjiku, a prosperous merchant and business man in 19th Century Prishtina. The rooms have been preserved as they were in the 1850s and can only be seen by guided tour (in English) from Ilir Sopjani, the museum director, who will enthusiastically explain how Gjiku’s family used each room and what daily life was like in Ottoman-occupied Kosovo.

I had visited the Ethnographic Museum on my previous visit to Prishtina, but I wanted to stop by and tell Mr. Sopjani that I had returned to Kosovo as promised (even if it was by a happy accident!). Imagine my shock when he remembered me and insisted that I join him for some freshly-squeezed orange juice in the museum courtyard. It was nice catching up with him and I thanked him for making my return to Prishtina extra special.

Xhamia e Jashar Pashës (Jashar Pasha’s Mosque)

Next to the Ethnographic Museum you will find Jashar Pasha’s Mosque, originally built in 1834 and recently restored with aid from the Turkish government. The unique wood paneling is cut in a specific Kosovar style and is one of the only buildings in the capital to still possess its Ottoman-era wood carvings. Jashar Pasha was a native of Prishtina and eventually became the mayor of Skopje in the mid-19th Century. This mosque was built in his honor and still functions today.

Off to Skopje

Speaking of Skopje, I barely had time to grab a quick bite at my favorite vegetarian restaurant in Prishtina, Dit’ e Nat’, before scurrying back to the bus station just in time to catch my 18:00 ride to North Macedonia.

What all started with a pang of panic at the Tirana bus “station,” had transformed to a glorious afternoon, giving me the unexpected gift of spending some time in a city I truly love. My only regret was that I was leaving again so soon! Until next time, Prishtina; this is definitely a “see you later” and not “goodbye.”