A trip to Chatuchak, a district in northern Bangkok, will allow you to visit two of my favorite attractions in the whole capital: the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and the Chatuchak Weekend Market. You can easily spend a full day at these two locations, but make sure you make the trip up here on a Saturday or Sunday; as the name suggests, the weekend market is only open on, well, the weekend. (MOCA is open Tuesday-Sunday; closed Mondays.)

There is a BTS Skytrain stop that lets you off right in front of the market. From there you can catch a bus or a cab to MOCA. I recommend heading to the museum in the morning- MOCA is massive and it took me nearly five hours to soak it all in- and then making your way over to the weekend market for a late lunch. There is an excellent coffee shop/cafe at the museum if you need a snack to tide you over until you can consume some real sustenance at the market.

Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA)

MOCA is one of the newest museums in Bangkok, having just opened its doors in 2012. Boonchai Bencharongkul, a Thai telecommunications mogul, also has a great passion for contemporary art and has been collecting it for decades. Art is everywhere in Thailand, but much of the art you encounter is religious in nature: giant golden Buddhas and mosaics in temples. But in the shadows, a burgeoning contemporary art scene has been flourishing since the 1980s and Bencharongkul believed it was finally time to thrust it into the spotlight. These incredible Thai artists were finally going to get their due. Bencharongkul also had a powerful ally in the Royal Family: Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn helped promote the museum and presided over its opening ceremony.

The first piece that greets you at MOCA is “Happiness,” a giant lotus flower in the reflecting pool near the entrance. In Thai culture, the lotus flower is a symbol of spiritual awakening. The plants sprout in the mud, after which their stems make their way through the water until the blossoms open, appearing to float above the surface. I took this giant lotus to represent the nation’s awakening to contemporary art and really legitimizing what it has to offer. It’s been a long road, but Thai contemporary art is being legitimized.

Also in the outer gardens is a statue of Ganesh, the elephant-headed Hindu god of wisdom, success and good luck. Many Hindu gods have been readily accepted into the daily lives of the prominently-Buddhist Thai society. How seriously these gods are taken I can’t say, but I gather that people treat them the way Catholics might treat their saints. Say a quick prayer to Saint Anthony if you’re lost or a quick prayer to Ganesh is you need a little luck- that kind of thing.

Known as the Father of Contemporary Art in Thailand, Professor Silpa Bhirasri, née Corrado Feroci in Florence, Italy, was invited to Thailand by Rama VI in 1922. He co-founded a school, which eventually morphed into Silpakorn University in 1943. Under his new Thai name, Bhirasri taught there until his death in 1962. He encouraged his students to blend traditionally European schools of thought (realism, Impressionism, post-Impressionism) with Thai subject matter.

Bhirasri’s motto at Silpakorn was “Ars longa, vita brevis,” which means skills take a long time (to develop), but life is short. If you want to become a true artist, you must devote your whole life to craft. If your time is divided, you will never achieve greatness. If you read the bios of the Thai artists featured in MOCA, almost every single one of them graduated from Silpakorn University. To this day it remains the premier art school in the country.

Example number one: Thongchai Srisukprasert, born in 1963, later would go on to receive BFA and masters degrees from Silpakorn University. His work, “Great Hornbill Lady,” welcomes you to the museum. Hornbills are genetically coded with a “monogamous instinct,” which is to say that once a pair mates, they will mate for life and not seek out other partners. Humans, naturally, have a more transient view of love, falling in and out of it throughout one’s lifetime. Here, Srisukprasert has given a human woman the head and wings of a hornbill, perhaps imbuing the human race with a love instinct that will last forever.

(General Disclaimer: please excuse my taking of slightly crooked photos. It is very difficult to take perfectly straight photos in an art museum!)

Janehuttakarnkit is one of the leading female Thai artists currently working today. She was born in 1953 and was greatly influenced by Bhirasri’s teachings. In her painting “Bone Forest,” Janehuttakarnkit strips her subjects of their outer shells. Whether tall or short, skinny or fat, white, black or brown, we are all just the same skeletons underneath it all. (This idea is rooted in the Buddhist concept of non-uniqueness as well.) Here she also takes inspiration from the proverb, “The fairest rose is at last withered,” meaning that even the most beautiful and vital beings will eventually decay.

Next we will return to Srisukprasert and his painting of the “The Five-Faced Brahma.” Brahma, the Hindu god of creation, is typically depicted as having four faces: one to watch each of the four cardinal directions. Originally though, Brahma had five faces, the fifth of which looked upwards and represented Brahma’s growing ego. Shiva eventually cut off Brahma’s fifth face, but here Srisukprasert presents him in his rarer, earlier form. The Brahma does not seem ravaged with a tyrannical ego either- just the opposite. He appears calm, peaceful and with closed eyes. Perhaps the artist is suggesting that some ego is good and healthy for the spirit. Contemporary art often challenges the status quo and a painting like this cause a Hindu or Buddhist viewer to re-examine their beliefs about Brahma.

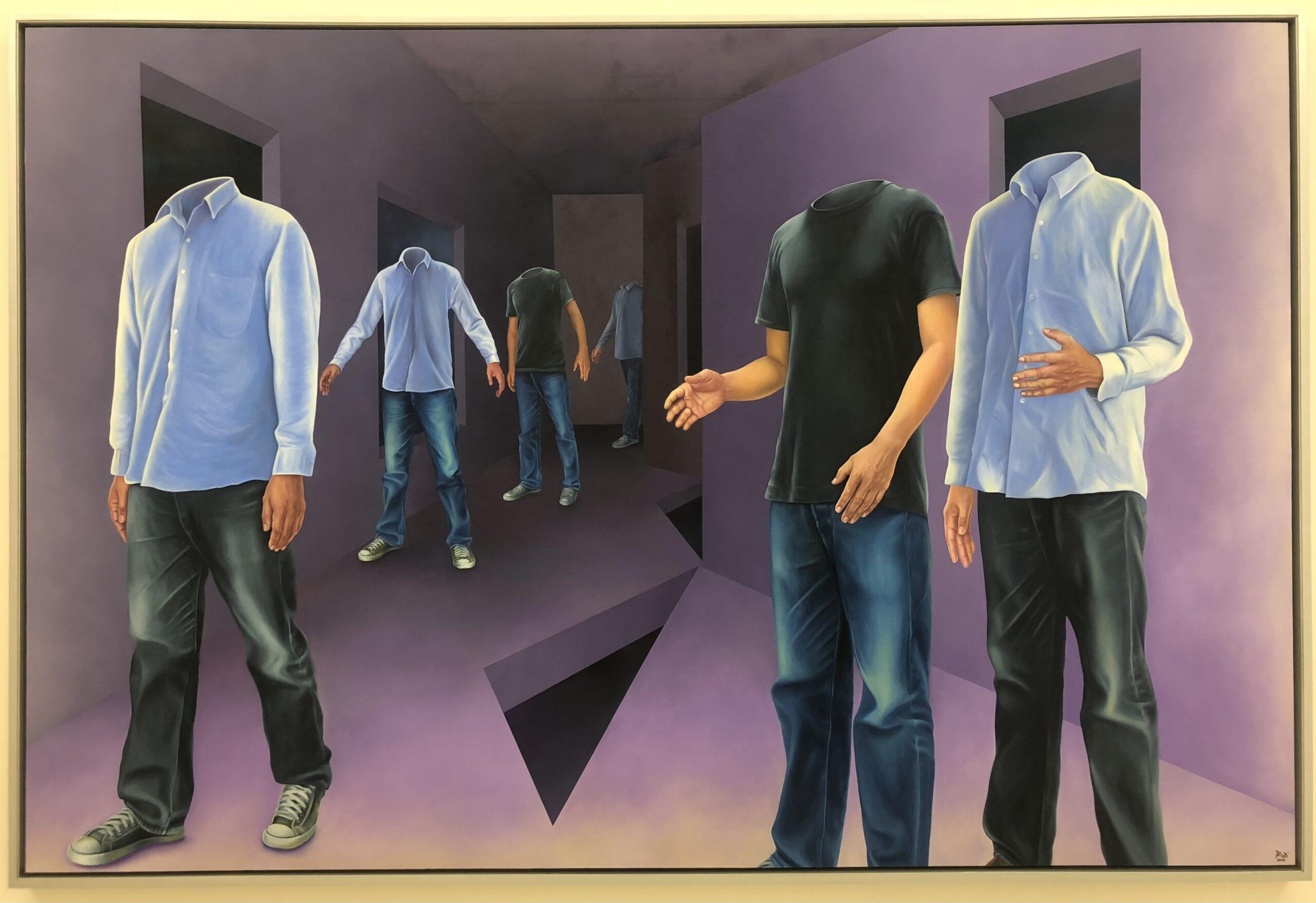

In Buddhism, there is a difference between the “learning” and “unveiling” of knowledge. Learning is easy. 2 + 2 = 4; Fe is the periodic symbol for iron; Angela Merkel served four terms as the Chancellor of Germany. Unveiling is the obtaining of truths of the universe. It is the opening of one’s mind to the world. In the above painting, Srisukprasert uses a triangle to represent everything a human possesses. The wider your base of knowledge at the bottom, the higher the pinnacle of the triangle will become. Deep inside the triangle is the unveiling of the realm of truth inside of every person. This, combined with your learned knowledge, represents where you are in your life’s journey.

Even though one may erroneously think of contemporary Thai art as being a departure into the secular world, one can never truly sever the cord between the Thai people and their Buddhist roots. “In Praise of Lord Buddha,” shows Kositpipat’s desire to follow Buddhist dharma, or the teachings of the Buddha. Through meditation and the renouncing of material possessions, Buddhists hope to break the cycle of rebirth and reach Nirvana. This is look at the path to enlightenment may be contemporary in style, but fairly traditional in substance.

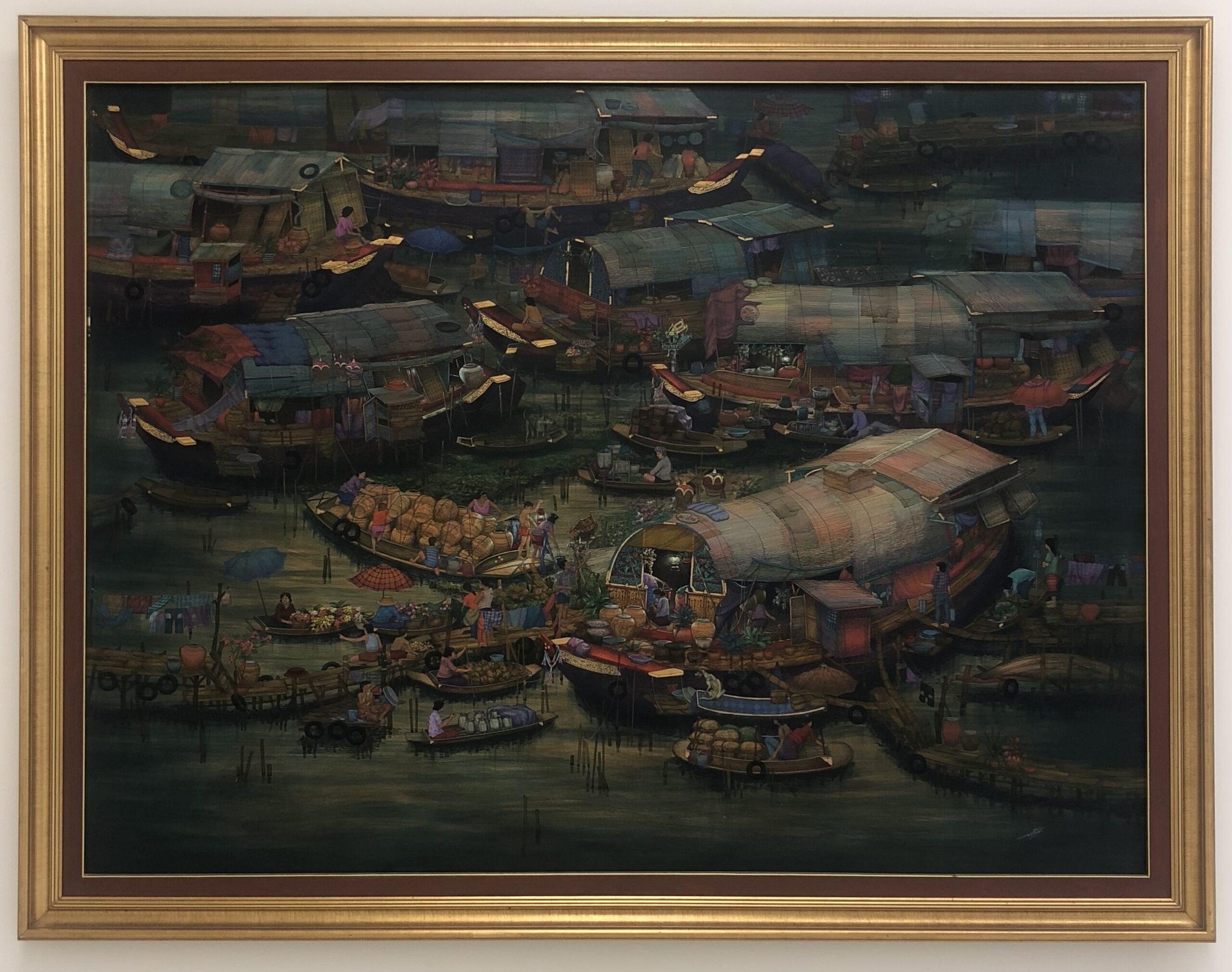

Bhirasri encouraged his students to depict scenes from daily Thai life in their paintings and sculptures. Up until this point, so much of Thai art was wrapped up in portraying lofty subjects, like the heroes in epic poetry or the Buddha himself. Why immortalize “lowly” fisherman on canvas? Vorasan Supap, another Silpakorn grad, has made a name for himself painting scenes of river life along the Chao Phraya. Supap believes that the Chao Phraya is the main artery of Thai life and culture, and has been that way for centuries. In his words, the river is a source of “simplicity, tranquility and warm sympathy.”

As someone who wakes up well before 5:45am to go to work, I can greatly appreciate this early morning scene of the workers of Bangkok, living on the outskirts of the capital, rising early in the morning to start their day and keep the great city running. Without the masses who make Bangkok hum along everyday, the city would cease to function. Supap removes pieces of each boat’s exterior, allowing the viewer to peak inside and see a glimpse of these pre-dawn rituals.

From the prosaic day-to-day of river life, to the thrill of modern Bangkok, all aspects of contemporary Thai culture are represented at MOCA. In “Glamorous Night in Bangkok,” Preecha Pun-Klimt shows us the blur of lights and color in the capital city. Buses, Tuk-Tuks, motorcycles and cars zoom past skyscrapers and temples on a nightly basis. Bangkok is a harmonious blend of the tradition and technologically-advanced modernity that just seems to work. You could never say that the Thai people have abandoned their past, but on the other hand, they have fully embraced the future.

Kiettisak Chanonnart’s “The Steps of Life” is one of my favorite paintings in MOCA. Absolutely fascinating and arresting, these headless bodies represent our march through mundane daily life. Most days’ steps are ordinary. We remember life by our milestones, both high and low, but the majority of our time on this Earth is spent dealing with the day-in, day-out of average life. The figures are given their arms and hands to help them keep their balance and avoid the pitfalls life throws at us. The two figures on the right have left the procession of the daily grind, not yet passed on, but still slowly moving in place, guiding the younger generation on.

Another thought-provoking piece, this time by Suradej Wattanapraditchai and entitled “Toys in 2008.” In the foreground we see two young boys, with dress and hairstyles from an older time and place. They have stumbled upon a group of children obsessed, not with playin in nature or with each other, but rather with the screens in front of them. While Thailand has fully embraced technological advancement, at what price does this come with in regards to the impact of screen time on a nation’s youth? We can’t see the faces of the two boys looking at their modern counterparts. Are they intrigued? Disgusted? Jealous? Bewildered? It’s up for the viewer to decide.

Amarit Chusuwan’s humorous installation, “The More I Get to Know Men, The more I Love My Dogs,” has three figures watching videos of dogs, as they themselves are posed as dogs. As we meet others in life, we hope to find kindness and sincerity, but often we encounter greed, cruelty, deception and corruption. It is our pets (I will include my own cat, Carl Magnus, in this), who are the true bearers of love. Perhaps we should strive to be more dog and catlike than take on the characteristics of our fellow humans…

In a contrasting installation, “Animal-Man Family,” artist Anupong Chantorn depicts a corrupt family who have been reincarnated as a pack of dogs. Chantorn believes an infection of greed and materialism has entered Thai society causing moral decay. If we are not careful, we can easily become susceptible to their powers and risk what effects it will have on our collective karmas.

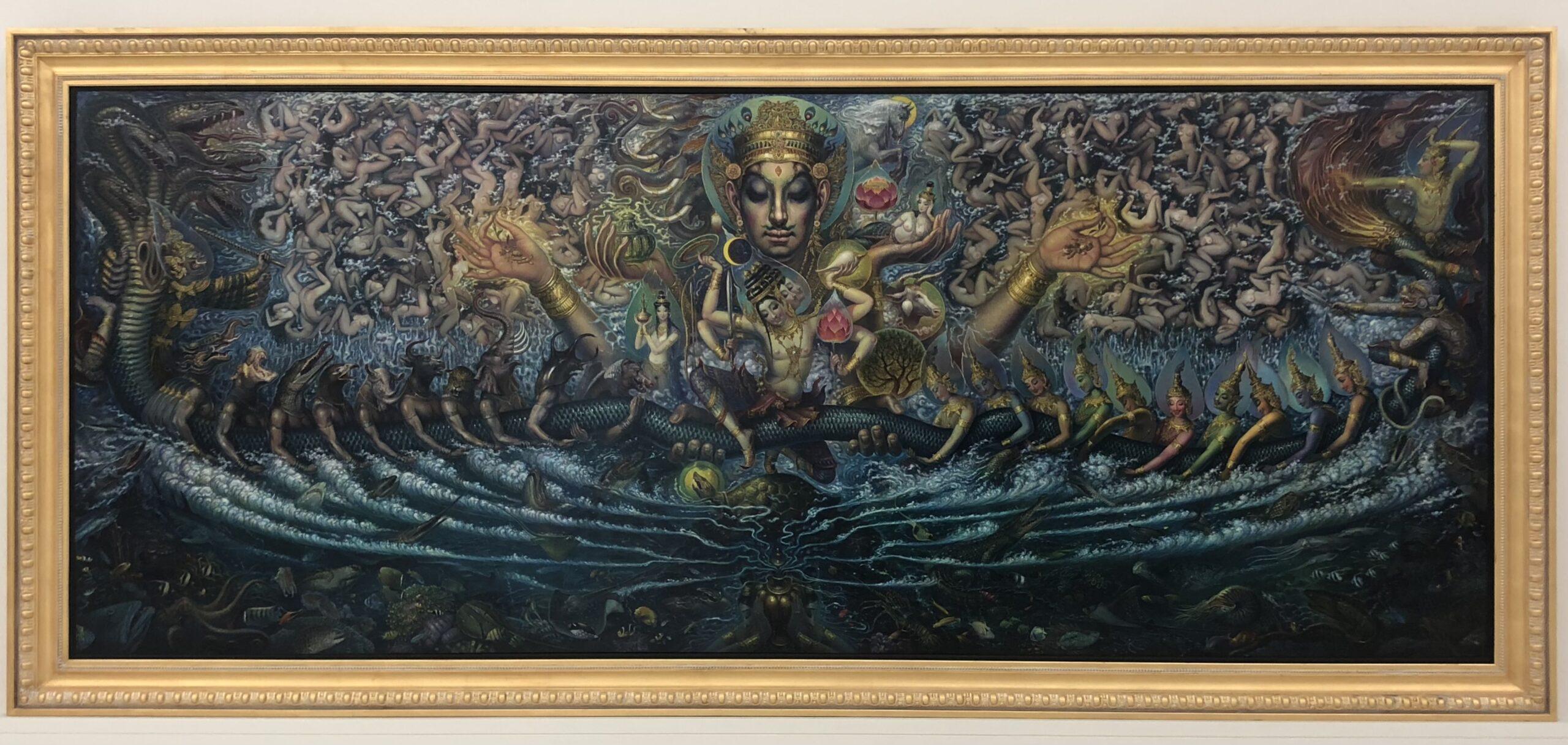

MOCA’s third floor has been set aside to take you on a trippy trek through Thai Surrealism; until visiting, I’m ashamed to admit that I didn’t even realize such a genre of painting existed! The above painting, “Churning of the Milk Ocean,” by Prateep Kochabua, tells the story of Indra gaining her immortality. The angels and demons had been at war for millennia, but they came together to churn the ocean, which would produce the nectar of immorality for the goddess. The angels are on the right in the painting; the demons on the left. They used a giant python that they tugged back and forth in order to churn the seas foam. But Indra had a trick up her sleeve: she knew rubbing the python would cause it spew venom from its skin, burning the demons. The demons were replaced by aquatic animals, and in that moment, the nectar of immortality was released.

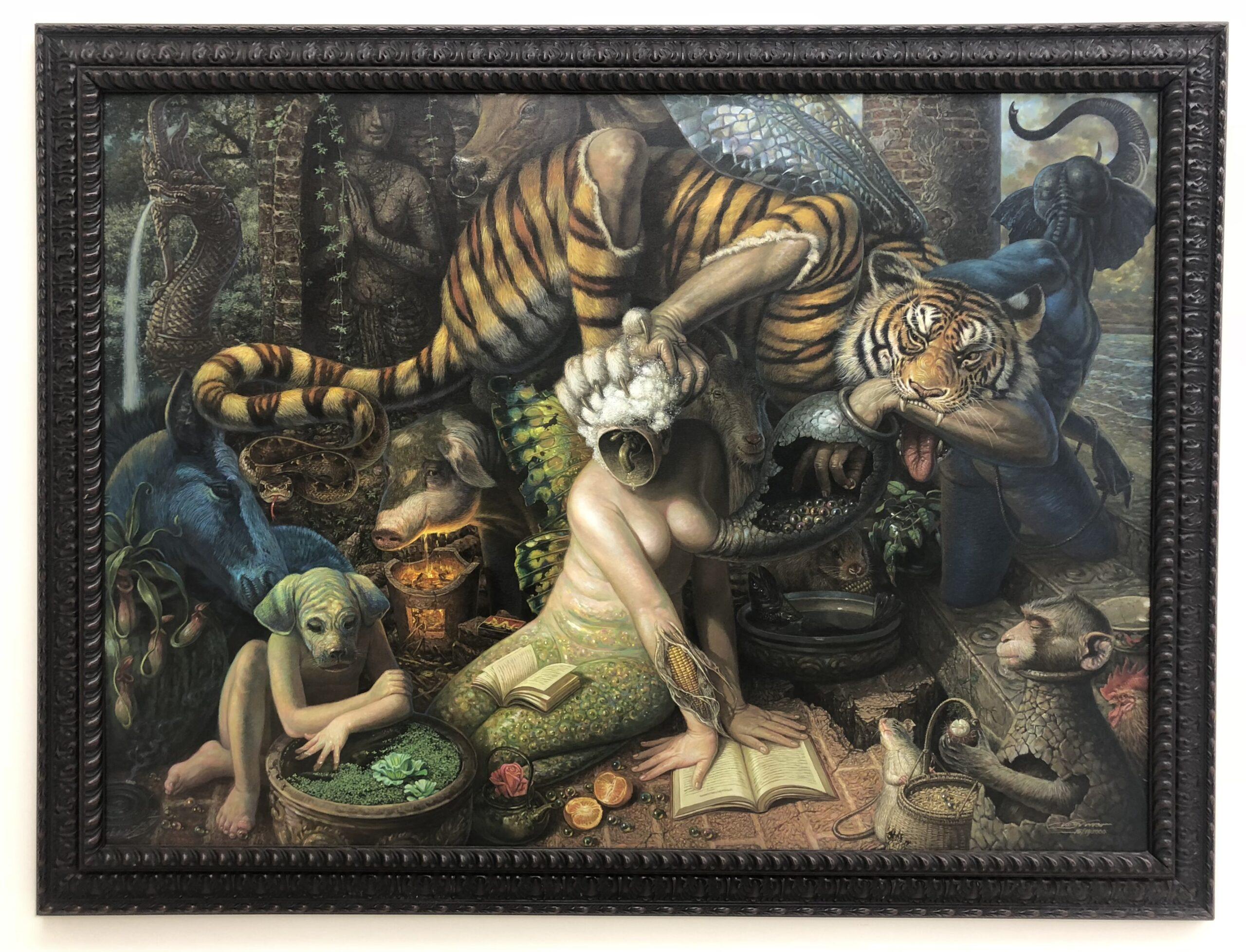

“At Your Beck and Call” really takes us several steps further into a surrealistic landscape. We have a female figure with the face of a water tap and a wrist of corn, a man who appears to be wearing the skin of a tiger (or is it a tiger wearing the skin of a man?), a child with a dog’s head, a monkey in a pot and a snake appearing from the tiger’s tale. Is the natural world at the beck and call of man or is it man who is controlled by the natural world?

In “Dream Land II,” we have exploded into a full-blown surrealist fantasy. Fairy nymphs dance on the beach and it is impossible to distinguish the females of the forest with the roots of the trees. Kochabua has turned the corner from sensual and hit downright erotic. This is certainly a departure from the chaste religious art with which we so commonly associate with Thailand.

Now let us move on to the works of Somphong Adulyasaraphan, aka the Thai Salvador Dali. Born in 1947, Adulyasaraphan graduated from Silpakorn University, but initially found it difficult to make a living as an artist. He instead turned to photography, particularly animal photography. He spent a good deal of time at the Dusit Zoo, where he also studied the movement and form of the various animals on display there. Eventually he was able to establish himself as a painter, but the process was slow. Adulyasaraphan employs miniature brushstrokes from very small paint brushes; each painting requires approximately two years of his attention.

In the above “Corruption of Village and Town” the town officials sit around a table, but their heads have been replaced with dead animal skulls. The trees and land surrounding the town have splintered and grown barren. The natural resources have been hoarded and abused by the officials, but time is catching up with them, although they remain unaware of their fate. Adulyasaraphan has a strong vein of environmentalism surging through his works.

Our planet’s environmental outlook may be grim at times, but Adulyasaraphan gives us a ray of hope here in “A Land Where Life is Found.” A goddess on an island of decay bestows upon the world an egg from which hatches a new world with green trees, flowing water and animals coexisting with one another. One of the main tenets of Buddhism is rebirth: there is always another chance to start again and get things right.

Here in “The Scarecrow’s Dream,” Adulyasaraphan presents us with some of his favorite recurring motifs: scarecrows and eggs. Scarecrows are not quite living men, but they do have the form of man and carry out work/service a function in society. Adulyasaraphan will often mix humans, scarecrows and skeletons in the same composition, intertwining these different stages/states of being. The egg is an interesting thing. It is both fragile and easy breakable, but always resilient and charged with protecting the life that is held inside. We see the scarecrow on his perch, observing the snakes and gnarled plants in the river. He dreams of a new river, pure and clean, that can cure his current water’s ills. Notice that the eggs are presented as paintings within a painting. The scarecrow holds the new art up to his current reality. Is the art the only place where we can find a happy ending or can it exist in the “real world” too?

In “Scarecrow’s Village,” the scarecrows are lifeless, standing around, observing the destructions humans have wrought upon their village. Deforestation, overfishing and planting too many corps over a given time frame have irrevocably harmed the ecosystem. Adulyasaraphan posits that perhaps the only thing humans have left to do to save the planet is to allow their decomposing bodies to refertilize the ground. (A bit dark, but hey.) Adulyasaraphan grew so disgusted with man’s treatment of the planet, that he went into a self-imposed exile for nearly 20 years on a farm in rural Thailand. It wasn’t until the opening of MOCA that he came out of hiding, ready to display his artwork again.

Bottom: “Gazing at the World Through the Gate” by Somphong Adulyasaraphan

In these two pieces, Adulyasaraphan attempts to move the remaining bits of untarnished earth in a Noah’s Ark-type attempt to keep it safe. Flora and fauna only seem to thrive and find a modicum of safety in botanical gardens and animal sanctuaries; the wild provides little security for the no-longer-wild. We still see the eggs of hope, but the ground is littered with the skeletons of unfortunate animals who could not hop on board and be rescued.

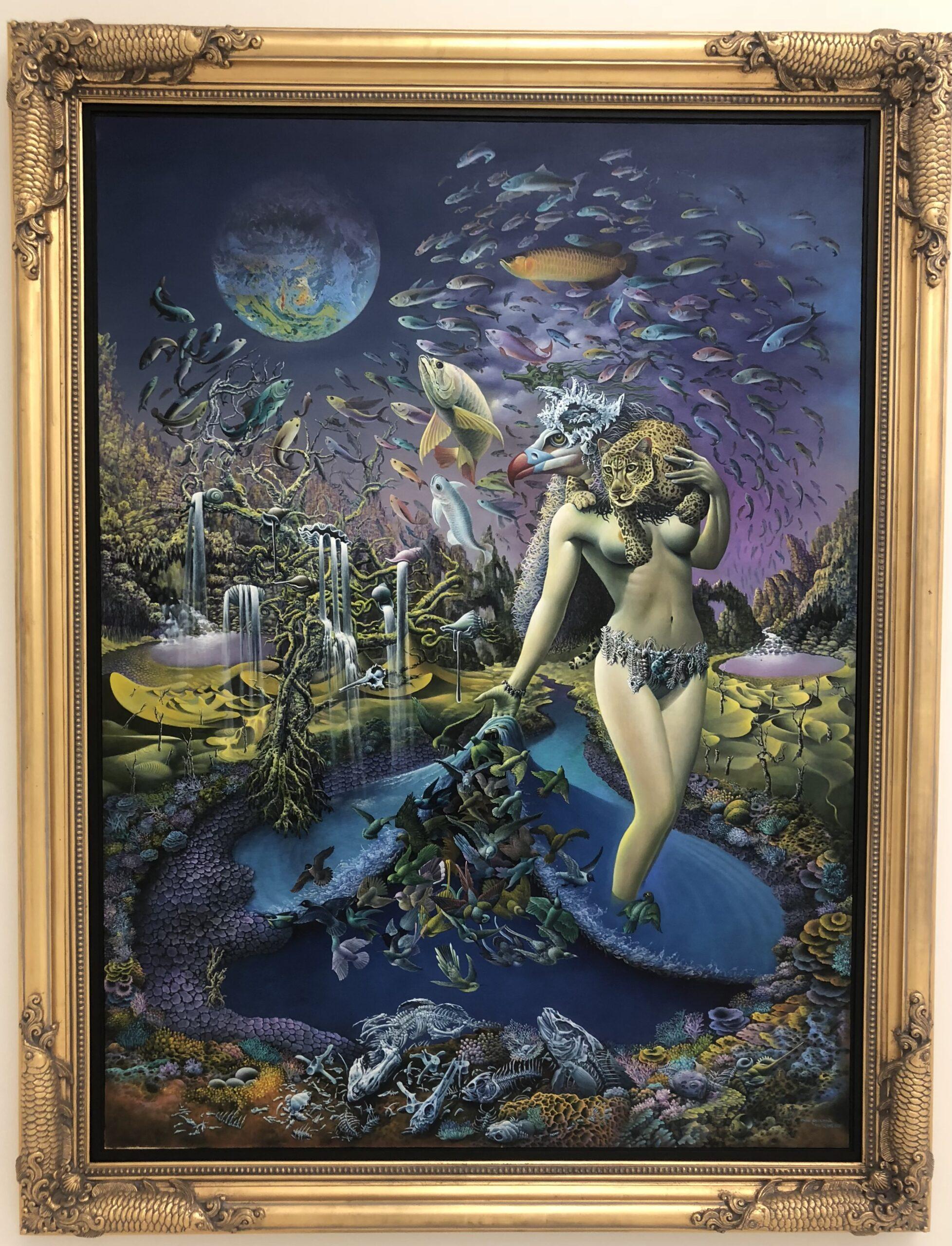

From the depths of despair, to a font of hope, Adulyasaraphan returns to a brighter future with his “Rainbow-Colored Fantasy.” Here a goddess pulls up the surface of the water to release an explosion of healthy wildlife that will replenish the world. Fish dance through the air and the surrounding land is lush and green. The jaguar, a symbol of beauty and strength presides over the goddess’s endeavor.

I’ll wrap up our look at Somphong Adulyasaraphan with the way we started looking at Prateep Kochabua’s works: with a myth. The Phra Aphai Mani is the single longest poem in the Thai language. It is 48,700 lines long and took Sunthorn Phu 22 years to complete. It is considered a national epic and taught in every school today. The poem tells the story of Prince Aphai Mani, who is led by a siren/mermaid to the island of Koh Samet (Koh is the word for island in Thai). This paradise is an unblemished land, not yet spoiled by the greed of man. Will we follow the the siren to Koh Samet or is this a trap? If we find Koh Samet, will we simply destroy it too?

“The Celestial Realm” by Sompop Budtarad

“The Human Realm” by Panya Vijinthanasarn

“The Unfortunate Realm” by Prateep Kochabua

The pièce de résistance at MOCA is undoubtedly “The Three Kingdoms,” which is a triptych painted by three different artists has been given its own hall in which visitors can repose on benches and take in its splendor. From left to right, the paintings depict the celestial, human and unfortunate realms. In Buddhism, you can be reincarnated into any of these realms depending on the state of your karma at the time of your death. It is only in the human realm that one can reach Nirvana and escape the cycle of suffering, or samsara. The unfortunate realm is full of pain and suffering, while the celestial realm holds delights beyond what the human mind can comprehend. It is only the human realm where we can understand and focus on reaching enlightenment with the help of the Buddha’s wisdom and dharma.

Something unique about the contemporary art found in MOCA as compared to the contemporary art I have viewed in so many other countries is the intrinsic spirituality found in so many of the works. Often, especially in the West, contemporary art is either devoid of religious influence or actively combatting religious institutions and their dogma. Interacting with Thai contemporary art feels so different because it wants to exist within the framework of Buddhism rather than deconstruct it. The art may challenge the viewer, but the artists do no seem to wish to challenge their Buddhist beliefs. Buddhism is still the main tool with which the artist can explain and uncover the truth in his or her world. Perhaps what I love the most about contemporary art is that it’s less about “learning” and more about “unveiling,” if you’re open to it.

Chatuchak Weekend Market

After you have had your fill of contemporary art, say au revoir to MOCA and head back down to the weekend market. I certainly had built up a decent appetite and now it was time to eat! It is absolutely worth planning your Bangkok trip around a trip to the Chatuchak Weekend Market, the largest in the country. With over 8,000 stalls, you will be lucky to even see a fraction of it on single visit. I was there mainly for the food- of which there is an abundance- but you can find anything you could possible imagine at the market.

For example, a stall full of silk flowers in every color and variety imaginable!

Handmade lampshades and hats!

Plastic fruit, because why not?

Candies, dried fruit and nuts galore! As you can see, this is a living, breathing market, not just something set up for the tourists, who certainly are not there to buy silk flowers and lampshades. Real locals come here to shop and the place, despite its size, is packed.

Back to what I really wanted: food, glorious food. It’s pretty easy to find a vegetarian meal in Thailand. Buddhist monks eat a vegetarian diet and many regular citizens follow suit. The one exception is that sometimes fish/seafood isn’t considered “meat,” but other than that, the concept of vegetarianism isn’t foreign to them. Tofu is a common protein and my only dilemma was selecting from which vendor I would purchase my lunch. My meal may not have been plated with much care, but it was delicious.

It’s interesting to witness something you see as “commonplace” be regarded as “exotic” and vice versa. It’s a good reminder that the word “exotic” doesn’t really have much intrinsic value. Garlic bread, hardly exotic in the US, was having a trendy moment in Bangkok as an exotic oversees import. One person’s “exotic” food, is just another person’s dinner.

There was no way I was going to go to Thailand without buying some local Thai iced tea. You can see the man on the right mixing the teas to order, and of course, the stacks of Carnation sweetened condensed milk.

Quite the sugar high, but a perfect way to end my day! In fact, my whole experience in Chatuchak put me on a high. MOCA was a dream come true for a modern/contemporary art lover like me, and wandering the weekend market, noshing on Thai treats, was the perfect way to decompress afterwards. Sometimes we have struggles and setbacks on a trip, but on other days, everything seems to come together and present you with a perfect little memory. I probably couldn’t replicate this experience in one hundred different attempts, but this is the type of high that keeps me traveling, continually in search of the next perfect day.