Banglamphu

After the royal island of Ratanakosin, which we explored in the previous post, Banglamphu (Old Bangkok) is the next most-visited neighborhood in the capital. Communities built their homes on this formerly marshy tract of land hundreds of years before Bangkok was declared Thailand’s new capital in 1782. The word Banglamphu literally translates to “Area of the Mangrove Apple,” as the area was noted for these fruit-bearing mangroves that sprung up from the oft-flooded soil. Unfortunately, the last-standing mangrove apple tree of Banglamphu died in 2012 after the city experienced heavy floods the year before.

As Bangkok began to establish itself as Thailand’s preeminent urban area, Banglamphu received a dramatic makeover. The marshland was out and a new system of canals was in. Perhaps not as extensive as the canal systems in Amsterdam and Venice, nevertheless you can’t walk far in Banglamphu without bumping into a footbridge-covered canal crossing. By drying out the land and constructing a port along the Chao Phraya River, the neighborhood became a major hub for trade in Southeast Asia. With merchants swarming the area, hotels and guesthouses followed, portending the future for the glut of hostels that would one day make Bangkok the epicenter of the Banana Pancake Trail.

Khao San Road

Depending on who you talk to, Khao San Road is a highlight of any Southeast Asian trip, full of fun times and great memories, or the street represents the worst of what the Banana Pancake Trail has done to the region. Khao San translates to “Uncooked Rice,” a nice metaphor for backpackers who have just arrived and are getting their feet wet before venturing out on their gap-year adventure.

Seafaring traders rested their weary bones in the ramshackle hotels along Khao San Road in centuries past. After the explosion of backpacking tourists that occurred after the first Lonely Planet guides were published in the 1970s, a new type of lodging began to appear. 1982 saw the opening of Khao San Road’s current main-defining characteristic: the hostel. At the time, backpackers represented the counterculture; I’m sure they would be horrified by the “flashpackers” of post-2000 travel! Hostels were seedy backpacker hangouts where you could find dirt-cheap accommodation, free banana pancakes in the morning and socialize with fellow travelers, sharing tips on what to see and how to get there.

Over time, backpacking has gone mainstream. Hostels are no longer the grungy lodgings associated with their image from the 1980s/90s. There are still simple hostels that offer a no-frills experience (clean bed and hot breakfast), but nowadays there are as many flavors of hostel as there are of backpacker. Some hostels cater towards families, while others aim to attract partygoers with pub crawls and in-house bars. Other hostels market themselves to digital nomads who require fast WiFi connections and peace and quiet in which they can work. Boutique hostels can be just as luxurious as a four-star hostel (and equally as pricey!) for those enjoy the social aspect of a hostel, but still demand pampering. Personally, I look for the “social hostel.” This genre of hostel is not as wild as a party hostel, but is not dull like the family hostels tend to be. People like to hang out in the common room and socialize, but they still desire a good night’s sleep. For the 40-50,000 backpackers who stay on Khao San Road during high season each day (20,000 during the rainy season), hostels of every type and size are there for the taking.

Nowadays, this backpacker ghetto has evolved into something resembling the Vegas Strip. The road extends only about one kilometer, but a cornucopia of vice has been crammed within the thoroughfare’s borders. Nearly 300 street vendors line the sidewalks, selling food, cheap souvenirs, fake Ray-bans, Gucci purses and other assorted made-in-China junk. Bookshops and tattoo parlors will also sell you pirated CDs, DVDs and fake IDs. There are bars, karaoke joints, comedy clubs, dance clubs and don’t forget the infamous strip clubs and ping pong shows where women launch ping pong balls out into the audience, shot out of their vaginas like a cannonball. (Massage parlors, often masquerading as brothels are a dime a dozen here too.)

The cheap street food is delicious, but this den of iniquity has given Bangkok and backpackers in Southeast Asia something of a bad rap. Of course, some people come to Bangkok expressly for the 24/7 party atmosphere at Khao San Road, but don’t let this prominently-touted image of Bangkok and Banglaphu scare you away from the city if it’s not your scene. I had no interest in partying (I have more of a let’s-wake-up-at-8:00-to-be-first-on-line-at-the-contemporary-art-museum vibe) and I got along at a social hostel right off of Khao San Road just fine.

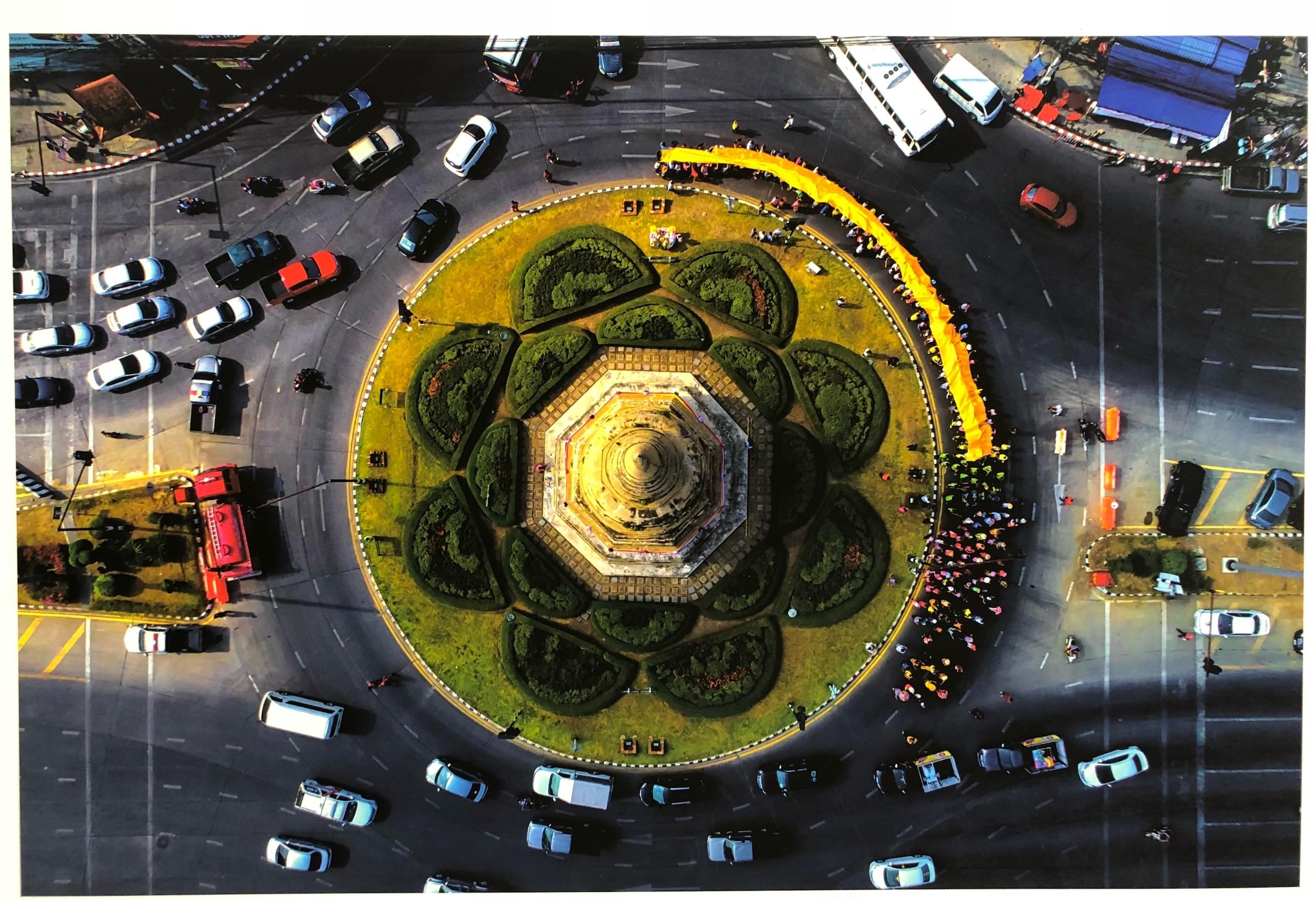

Democracy Monument

If you remember from our mini history lesson in the previous post, in 1932, Thailand (then called Siam), experienced a revolution that ended the absolute monarchy and created a constitutional monarchy in its place. This should have brought about democracy in Thailand, right? Well, not quite, but more on that later.

The monument was commissioned in 1939 by the military-installed prime minister, and was designed by architect Mew Aphaiwong. Each of the four wings is 24m (78ft) tall and the base of the monument also has a radius of 24m; both measurements honor the new constitution’s ratification on June 24, 1932. Atop the middle column, you can see a golden manuscript box placed above two Buddhist offering bowls. Inside the box is an engraved copy of the constitution. The bas-relief sculptures at the base of each wing were created by Italian artist Corrado Feroci, who later became a naturalized Thai citizen.

Despite it’s name, the Democracy Monument was a crafty bit of government propaganda. The 1932 Revolution was bloodless- the king was away on a beach vacation when the monarchy was overthrown- and led by a small group of military officers and civilians. Rama VII, the king at the time, fled into exile and eventually abdicated the throne. Rama VIII was crowned king while he was a mere boy away at boarding school in Switzerland. The military leaders and intellectual elite who crafted the constitution had different ideas of what “democracy” should look like. The two groups increasingly fought throughout the 1930s and by the end of the decade, Thailand had effectively become a military dictatorship.

The military leaders wanted to westernize the country and model Banglaphu after European capital cities. Ratchadamnoen Avenue, an enormous two-sided roadway was built down the center of the neighborhood. Modeled after the Champs-Élysées, dozens of trees were chopped down and hundreds of homes and businesses were displaced to complete the project. The Democracy Monument was to act as an Arc de Triomphe stand-in at the avenue’s roundabout.

Feroci’s sculptures are where the real propaganda creeps in. The king is nowhere to be found on any of the panels. Instead you see members of the armed forces rescuing the people from oppression and giving them freedom aka purpose through work. (The sculptures share a lot in common with Soviet monuments built during the same time period.) In an effort to promote European sports and ideals, the Thai people are shown participating in activities such as the shot put, which had never been played in Southeast Asia.

The Democracy Monument has been a rallying point for protests over the years, notably in 1973, during “Black May” in 1992 when Rama IX stepped in to restore democratic elections in Thailand and again in 2013-14 when the nation was experiencing a financial crisis.

October 14th Memorial

Not far from the Democracy Monument is the October 14th Memorial, installed to commemorate the lives lost during the protests in 1973. The monument complex consists of the 14m (45ft) tall Stupa Saga, which depicts the quest for democracy, as well as an exhibition in the background detailing what led up to the deadly affair. The tip of the stupa is clear and emits a light at night to symbolize democracy shining in Thailand. (The memorial was constructed in 2001 and designed by Thai artist Terdkiart Sakdikamduang.)

Post-World War II, the United States actively supported the revolving door of military dictators that governed Thailand and in return, the government enacted pro-US policies. This incited students protests across university campuses and various pro-democracy organizations began to form, the strongest of which was the National Student Center of Thailand or NSCT, led by its charismatic leader Thirayuth Boonmee. In 1963, General Thanom became prime minister and became enemy #1 in the eyes of the students. Thanom dissolved parliament and 1932 constitution. He outlawed all political parties except his own and any bit of power was concentrated in his own hands or bestowed upon select family members in his inner circle.

The NSCT began holding rallies to protest this blatant corruption and tyranny. Not only students, but regular civilians joined the public gatherings that swelled to numbers of 50,000 protestors at a time. On October 6, 1973, Boonmee and ten others were handing out pamphlets in Bangkok, demanding a new constitution be written. Along with two others, these thirteen students were arrested, charged with treason and held in jail without bail. Bangkok went berserk.

By October 13, 400,000 had assembled on Ratchadamnoen Avenue to protest Boonmee’s arrest. Thanom, fearful of a coup, relented and agreed to free the thirteen and allow for a new constitution to be drafted the following year. Doubting the dictator’s promises, 200,000 protestors marched to the Grand Palace, demanding an audience with Rama IX. The king largely stayed out of political matters, but before he could convene with the protestors, police officers began throwing bombs into the crowd in an attempt to get them to disperse. Tanks rolled in and gunfire erupted. By the end of the day, 77 protestors had been killed and 857 were wounded.

On October 15, half a million people flooded the streets demanding justice. In the evening, Rama IX addressed the people and announced that Thanom had resigned and fled to the United States, where he would live in exile for several years. The student movement controlled the government for the next three years until the military honchos once again asserted themselves and regained power until democratic elections were finally held in 1992.

Mahakan Fort

When Rama I established Bangkok as the capital, one of his primary goals was to draft a defense system against Burmese invaders. A wall was built around the city, containing 63 gates and 14 forts; today only one of the gates and two of the forts remain. As Bangkok expanded, the defensive walls became obsolete. Rama VII decided to preserve the two remaining original forts in the 1920s, one of which you can see above in Banglaphu. Mahakan Fort is octagonal in shape and would have housed soldiers ready to protect the city in the event of an attack.

Behind the fort was a neighborhood of wooden houses, many of which were built 200 years ago. The city had been battling with residents for decades, attempting to purchase their land, demolish the wooden structures and erect a park and museum of the ancient city defense systems in their place. The project was tied up in court for years, but in 2019 the government finally won and tore down the houses of last families who were holding out on selling their homes. More green space and a museum devoted to the city’s history sound great, but residents argued that the needs of tourists were being placed above the actual citizens. I have sympathy for the people who were displaced and can empathize with feeling like the local government cares more about tourist dollars coming in than the local residents. Projects spring up all the time in New York that are of little to no benefit for the people who live and work here. Tourism can stimulate an economy, but the right balance between the needs of the locals and the wants of the tourists must continually be recalibrated.

Residential Banglaphu

It’s always wise to remember that the cities we visit are more than a list of tourist attractions to check off. These are neighborhoods full of people going to work and school, running small businesses and operating restaurants. Sometimes you need to stop scurrying from one monument to the next museum and just wander the streets and observe daily life. For most locals, life is not the glitz and glam of the Grand Palace or a night out at Khao San Road. Life is buying groceries and watching TV after a day at the office, just like anywhere else in the world.

Spend your tourist dollars wisely and with care. If you want a hat, buy one from a local merchant and not at the airport gift shop. Patronize a local restaurant and not an international chain. Sometimes the most memorable moments I have are not at the “top ten sights” in a given city, but rather they stem from random interactions I experienced with locals.

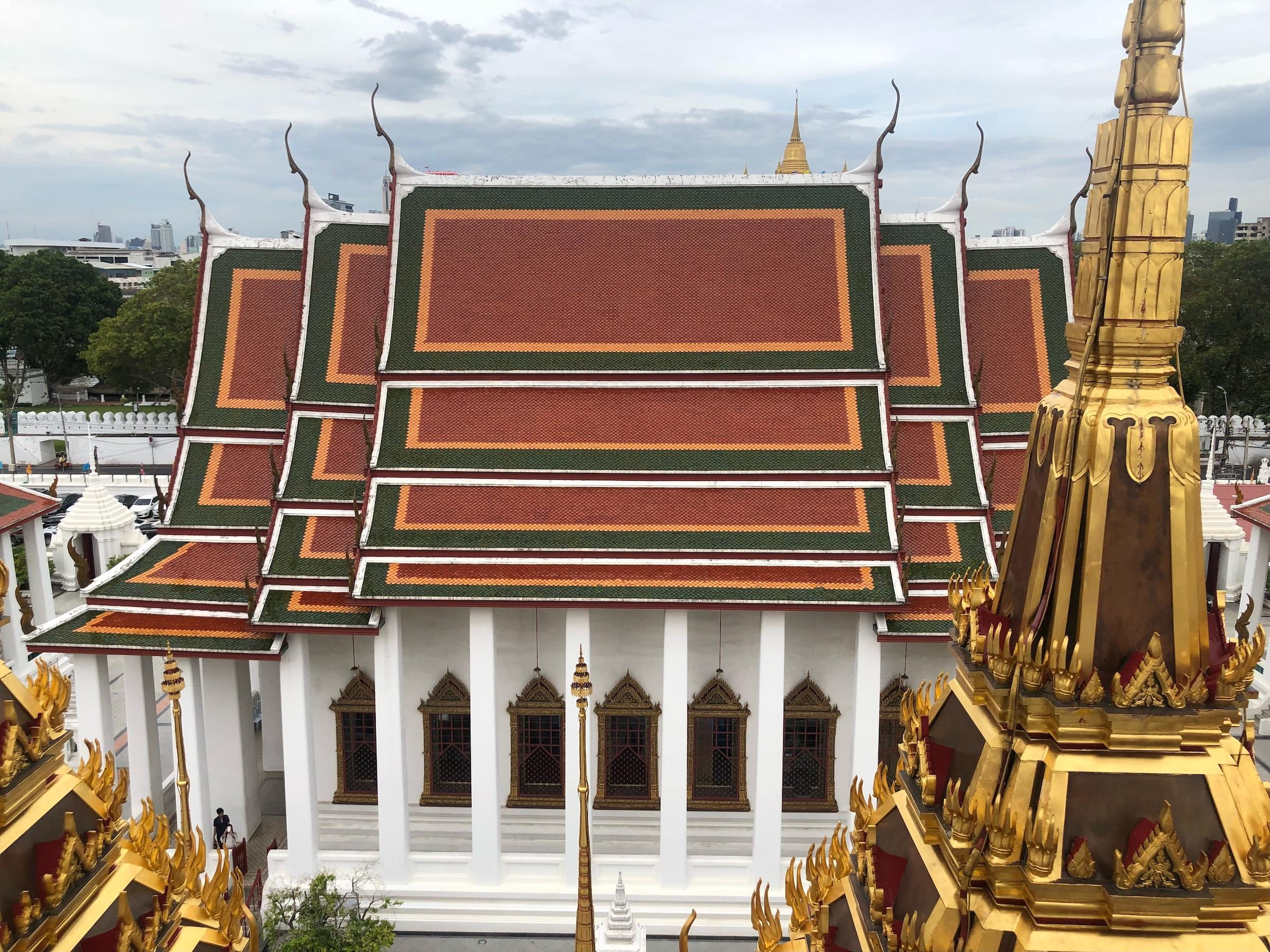

Wat Ratchanatdaram & Loha Prasat

With that said, Banglaphu does have a few temples and museums well worth exploring. Rama III began construction of Wat Ratchanatdaram in 1846 in honor of one of his favorite granddaughters (Wat Ratchanatdaram translates to Temple of the Royal Niece). The temple’s claim to fame is Loha Prasat, pictured above, which means metal castle. A Loha Prasat is a multi-storied holy building with a metal roof. Only three existed in the world- this one in Bangkok, as well as one in India and a third in Sri Lanka, the latter two of which fell into disrepair and were demolished, leaving the Loha Prasat in Bangkok as the last of its kind.

Loha Prasat has three levels, all accessible to the public via a spiral staircase in the center of the building. There are 37 golden Mondop-style spires on the prasat, representing the 37 virtues needed to achieve enlightenment.

Wat Saket & The Golden Mount

Rama III greatly expanded the canal systems of Banglaphu during his reign. One problem: what to do with all the dirt that was excavated while digging the waterways. The king had the idea to build a giant mound on the grounds of Wat Saket with the soil, which eventually grew to be 10om (328ft) tall and 500m (1640ft) wide at the base. Rama III wanted to cover the mound with brick and create an enormous chedi, but the marshy ground underneath it was not solid enough to support the project, and it was eventually abandoned.

Over time, plants and trees cropped up on the man-made hill, the only elevation of its kind in the otherwise flat-as-a-(banana)-pancake Bangkok. Rama IV added a small golden chedi to the top of the hill and the Golden Mount was born. Concrete walls were erected to reinforce the mound during World War II in an effort to fight off growing concerns of erosion; you’ll have to climb 320 steps to reach the summit.

The golden chedi at the top may be impressive, but the real reward for your climb will be the 360 degree panoramic views you can soak up of the capital. There are taller skyscrapers in Bangkok’s financial district, but that area is not nearly as centrally located as the Golden Mount. You will not find a better lookout in the city than right here in Banglaphu.

The Vultures of Wat Saket

Remember the 63 gates along the ancient city walls? Each gate was enchanted so that no evil spirits could breach the city, well every gate except one. Partu Phi, located next to Wat Saket, was not bound by any protection spells and was known as a “ghost gate.” Anyone who died within the city had their body carried through this gate, which allowed their deceased spirits to also depart the city. There was a crematorium at Wat Saket where all the bodies were burned.

Dating back to Rama II’s reign, cholera outbreaks plagued the capital from 1820 to 1881. 30,000 died from the disease that first year, and thousands more became infected each dry season thereafter. The crematorium couldn’t keep up with the work load and excess cadavers had to be placed in the temple courtyard. Flocks of vultures began nesting in the temple and scavenging bodies that were awaiting cremation. “Raeng Wat Saket” or “vulture of Wat Saket” has become a popular local saying to describe someone who acts like these birds of legend.

Rommaninat Park

When you’re visiting sights on the tourist trail, signage is usually translated into English, or at the very least, it is Romanized for Westerners to more easily read. The farther away you venture from the main sights, the more on your own you’ll be with the language. English is not widely spoken amongst the older generations, but I found younger people have a greater probability of being able to point you in the right direction if you get turned around.

You’re not likely to find Rommaninat Park on any “must-see lists,” but I really enjoyed this peaceful green space in Old Bangkok. Locals refer to it by its nickname “Khuk Kao,” meaning “Old Prison.” Rama V built an urban prison here and it grew in notoriety over the years as it housed some of Thailands more dangerous felons. The prison was eventually relocated outside of the city and the old building was abandoned and razed in 1992. Rama X, then the crown prince, opened Rommaninat Park in 1999. Unlike the controversy surrounding the demolition of the wooden houses behind Mahakan Fort, the destruction of the old prison, a symbol of violence and pain, was happily welcomed by residents.

Ratchadamnoen Contemporary Art Center (RCAC)

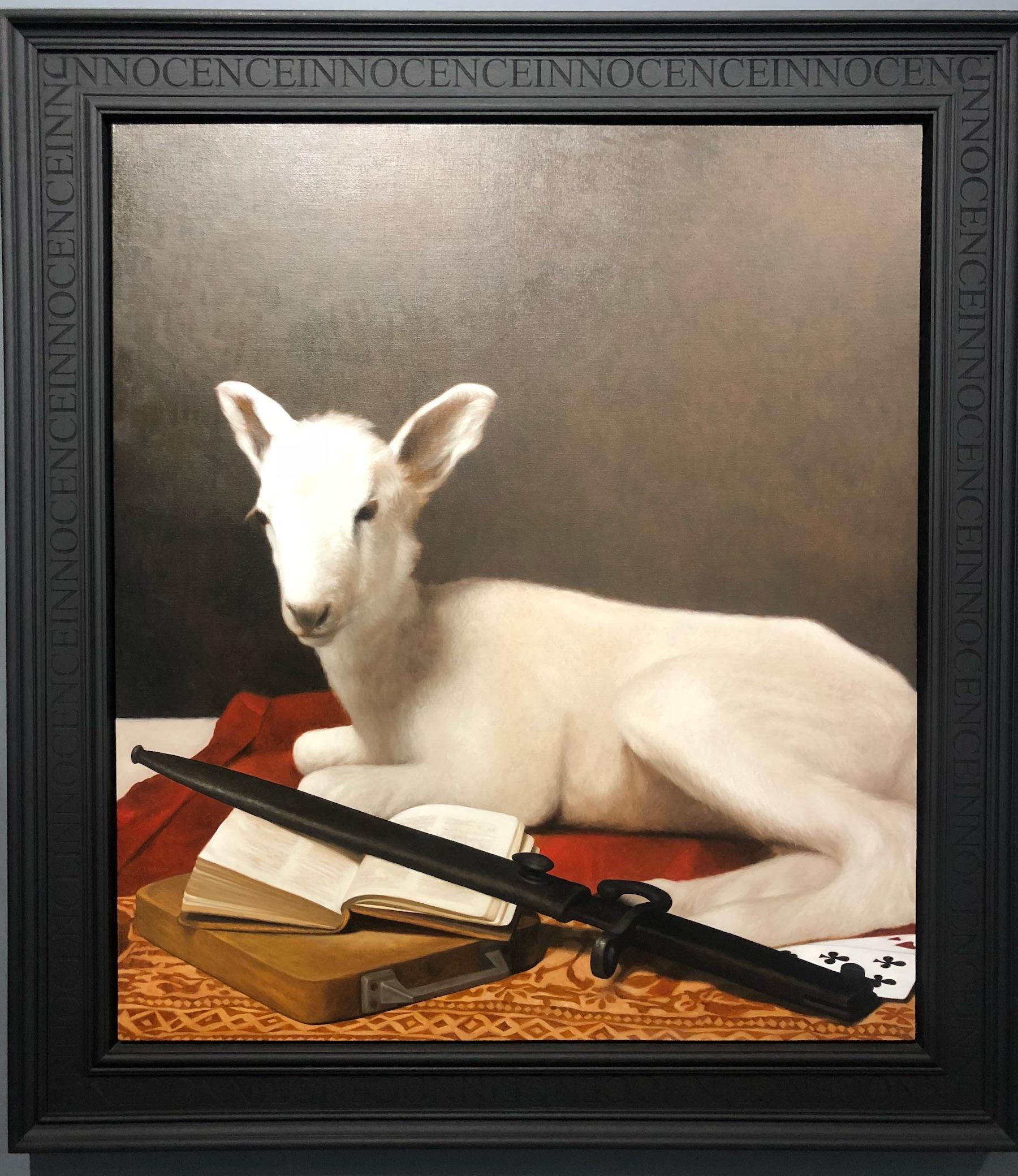

The Ratchadamnoen Contemporary Art Center (RCAC) is one of the latest additions to Bangkok’s growing contemporary art scene, having just opened its doors in 2013. Art has certainly been important to Thai/Southeast Asian culture, but for centuries, Buddhism and art were forever intertwined. Even the murals of the Ramakien epic commissioned by Rama I at the Grand Palace have religious overtones. Celebrating secular art is certainly on the rise nowadays, with more museums and art installations popping up seemingly overnight.

When Ratchadamnoen Avenue was widened in 1939 to make way for the Democracy Monument, new European-style buildings were constructed to line the street. The RCAC is housed in one such building, its patches of exposed brick and concrete after years of abandonment kept intact, creating an odd, yet harmonious environment in which the contemporary art is displayed.

To help praise and promote contemporary artists, the Silpathorn Awards were created in 2004. This high honor is given out in seven disciplines: visual arts, literature, music, film, performing arts, design and architecture. When I visited the RCAC, there was a special exhibition showcasing the works of that year’s award winners. Above are two paintings by Bangkok-born artist, Natee Utarit, who juxtaposes Renaissance-style painting techniques with contemporary subject matter.

Anan Nakkong won in the music division for his work with traditional Thai instruments including the Ranat ek, which is pictured above. This type of xylophone has twenty one or two wooden bars, often craved from rosewood, which are then suspended over a boat-shaped vessel that helps resonate the tones when struck by the two mallets. The Ranat ek is one of the primary instruments of a Piphat, an ensemble that plays Thai classical music.

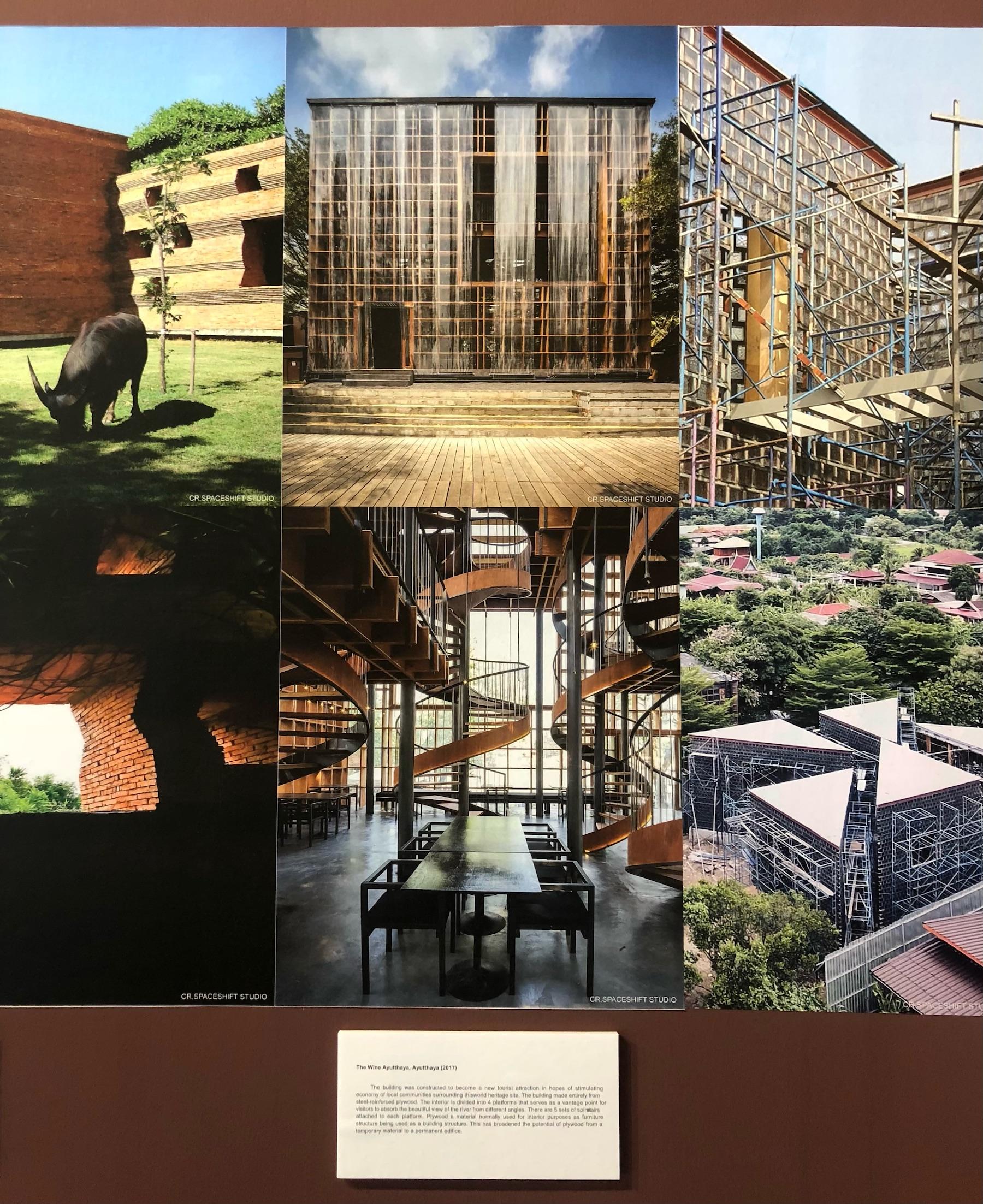

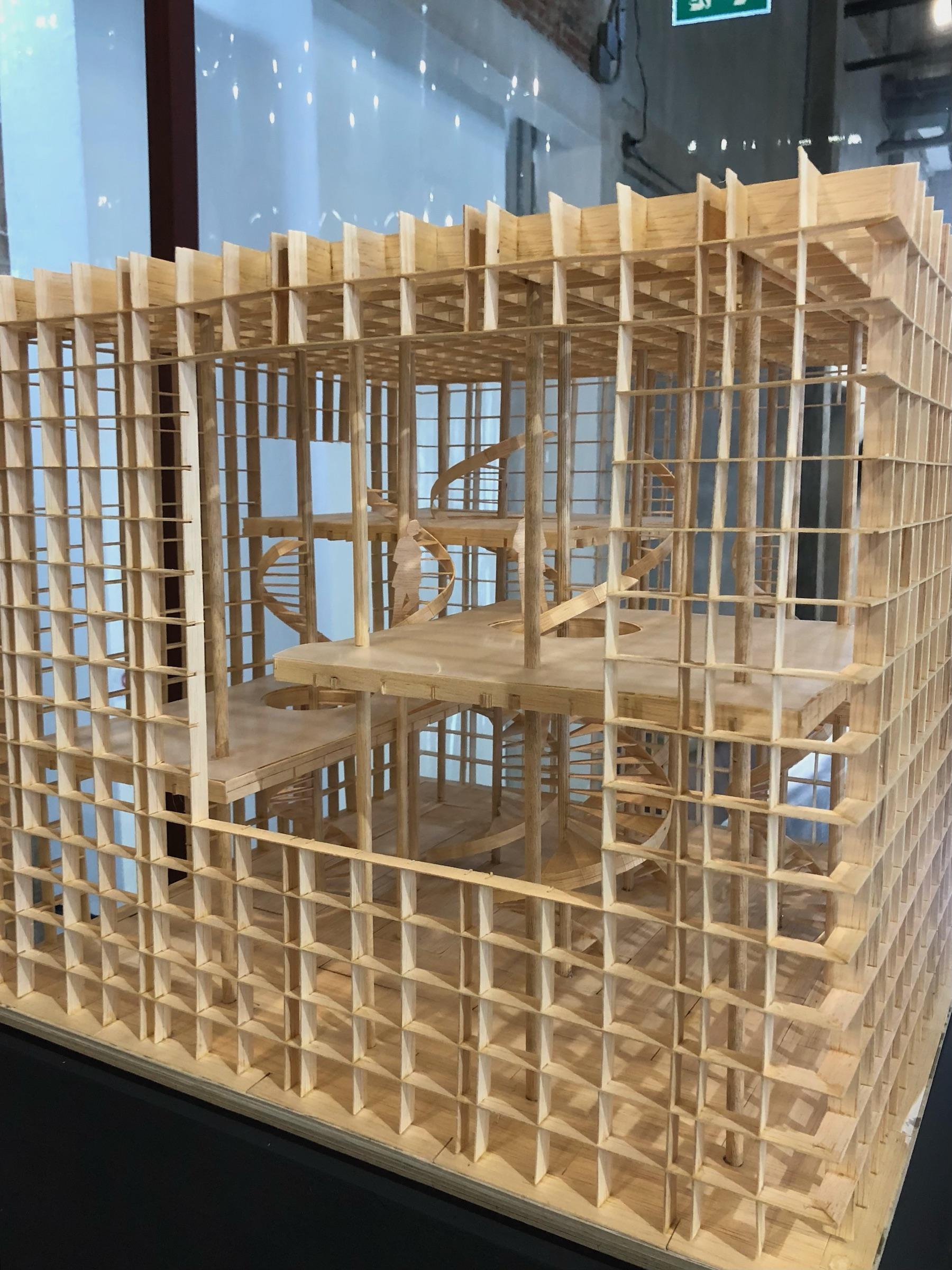

Architecture winner Boonserm Premthada designed a series of structures that would be incorporated into the natural environment at Ayutthaya, the former capital. Each building would be constructed from steel reinforced plywood. Normally a material hidden from view, plywood would take center stage in Premthada’s works. The spiral staircases would lead to viewing platforms that would look out over the ruins of Ayutthaya, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In “Upcycling Design Journey: Targeting Sustainability,” Singh Intrachooto took trash and turned it into furniture with a modern aesthetic. From eggshells to plastic bottles and bags, Intrachooto let nothing go to waste. He not only aims to protect the environment and reduce landfill buildup, but he is creating needed goods at the same time. This goes beyond recycling and enters upcycling. Above you see a bag of eggshells and then presto…

Why compost those eggshells when you can make a stool? Why recycle a plastic bottle, when you can transform its shards into fibers for a rug?

Sometimes we limit our minds in so many ways. What is a rug? What is a stool? What can make music? What should music sound like? What should a building look like? What materials can we use to construct this building? What can art look like? What can art say? If contemporary art has taught me anything, it’s to open my imagination and not to fall into rigid traps or what art should or shouldn’t be.

ASEAN Photography Contest and Cultural Center

The top floor of the RCAC is the ASEAN Cultural Center, the first of its kind in Southeast Asia. ASEAN is an economic, political and cultural union, founded in 1967 by five member states, including Thailand. Over the years, its membership has grown to ten: Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore and The Philippines. A new charter was drawn up in 2008 to model this partnership more like the EU than ever before. ASEAN has aided in stimulating trade between these nations and presenting a united front when negotiating import taxes and tariffs with countries outside the union.

Of course, each country within ASEAN has a unique cultural heritage, but the union also highlights cultural similarities across the region. As we examine the different neighborhoods of Bangkok, we can think along these same lines. Each area, like Ratanakosin and Banglaphu, offers something different, and yet they’re all part of Bangkok. Don’t worry about putting each little district in its own box. Life ebbs and flows through the whole city, which is in turn part of Thailand, which is part of the Banana Pancake Trail, which is a part of Southeast Asia and the ASEAN alliance. Understanding the details only helps you better appreciate the whole.

Below I will leave you with some of my favorite entries into the annual ASEAN Photography Contest. Can you guess which one is from Thailand?