Of the nearly 200 United-Nations recognized countries on this planet, it was the thirteen Caribbean-bound republics that I assumed would be my bête noire. Some of these fears stemmed from practical issues: it’s expensive to island hop and visit more than one or two countries on a single visit to the Caribbean and the hostel/backpacker scene is generally not thought of as well-established in these locales. But more than that, I was dreading coming here because I wrongly (and rather idiotically) believed that there was nothing to do on these islands except sit on the beach, piña colada in hand, and soak up the sun at an all-inclusive resort.

I will tender a full mea culpa and own up to my foolishness- there’s obviously more to a country than a sandy beach- but cut me some slack. How is anyone expected to think otherwise when the collective governments and tourism boards of these Caribbean nations have worked so hard to present the unified image that there’s nothing more to do in their respective nations, except kick back and relax in the crystal-clear waters surrounding their shores.

I could easily devote an entire post to this topic, but before I move on to my time in Scarborough, let me discuss all-inclusives and how damaging they can be to the local economy and citizens of an area. What exactly qualifies as an “all-inclusive?” Like the name suggests, it’s a resort where everything is included in an upfront fee. You have your room, three meals a day, endless alcohol at the hotel bars, spas, organized activities (such as snorkeling, aerobics, yoga, etc) and most importantly, access to a gated beach. Basically, you’re on a private, luxury compound where everything is provided for you. There isn’t any reason to leave the resort and few venture out to explore their surroundings. In a recent joint study between the UN and a UK research firm, only 20% of those who stay at an all-inclusive leave to eat a meal outside the resort or visit a cultural attraction/museum.

And why would they? They have already paid for all their food and drinks, and the plethora of activities at these resorts, from a couples massage to beach volleyball, can easily fill up a visitor’s dance card. The resorts are also very safe, employing private security personnel, and the beaches are kept immaculately clean. People like that they can pay $5000 upfront and then never have to worry about spending another dime while on their vacation.

So what are the downsides to staying at an all-inclusive and why are they so harmful? First of all, the food is notoriously awful at many of these resorts and it is totally catered to American/European palates. You’re more likely to find hamburgers, pizza and spaghetti on the menu rather than local cuisine. Secondly, you’re traveling all this way to a foreign country and culture and you don’t want to experience any of it? It seems like such a waste of money and opportunity when you could probably travel somewhere domestically (at least in the United States) and experience the beach at a fraction of the cost.

These examples illustrate how a tourist loses out, but what about the locals? While it’s true that these all-inclusive resorts employ many people, the same UN study found that they are often paid criminally low wages, have to work long shifts (the average was between 12-15 hours) and were hired under short-term contracts that provide little long-term job stability. In addition, these resorts are not owned by locals. 80% of the money collected does not find its way back into the local economy, but rather to shareholders abroad. Tourism can be a boon for locals, but only if those tourist dollars are finding their way into the hands of the people. Local restaurants, shops and museums, as well as enterprises that offer guides for hiking, snorkeling, paragliding, etc never see a drop of the money you spend at an all-inclusive.

The great news is that there is a fantastic, if small, backpacking/hostel trail throughout the Caribbean, and if you forgo the all-inclusive resorts, you will find an affordable destinations packed with all the history, art, culture and adventure you could ask for. It’s downright shocking and shameful that this side of the Caribbean is so poorly promoted, and honestly it pisses me off. So here I am, hellbent on righting my own misconceptions about the Caribbean and setting the record straight. Let me show you that there’s so much more to Tobago than all-inclusive resorts and sandy beaches. The capital of Scarborough is a vibrant and lovely city, and best of all, there’s not a single all-inclusive resort within it’s borders! There is a top-notch hostel, though, which will act as the perfect place to begin my Scarborough-history tour.

Hope Cottage

Hope Cottage is the “anti-all-inclusive” in every way, shape and form. Run by born-and-bred Tobagonian husband and wife, Len and Joan, as well as their son Mark, staying at Hope Cottage not only deposits your money directly into the local economy, but you get to experience a slice of authentic Tobagonian life and hospitality up close and personal.

I arrived at Hope Cottage about three hours before my check-in time and was prepared to simply drop off my backpack and occupy myself in town before I could freshen up after my flight. Joan would hear nothing of the sort. The couple had invited over family friends for lunch and insisted I pull up a chair and join them. Within five minutes I felt like I had known everyone around the table for years.

“I don’t understand how these mangos are so sweet and ripe,” I remarked to Len. “That’s because I just picked them from the mango tree in our backyard,” he replied.

After lunch, I was given a brief history of Hope Cottage. James Henry Keens, who was one of the British colonial governors in the 1800s, resided here during his rule. His burial plot, along with those of his wife and eight children, are still located behind the hostel. In 1940, the residence was converted into a guest house and more recently it has been incorporated into Trinidad and Tobago’s National Trust, a historical registry of protected buildings on the islands.

I hadn’t been on the island for more than an hour and I instantly knew I had sorely misjudged Tobago, and likely the Caribbean at large. But where was all this in my Lonely Planet guidebook (LP, you have failed again!)? Why does every bit of promotional material released by the government only feature sand or a poolside cabana? (Several Tobagonians and Trinidadians- or more affectionately, Trinis- told me the government was “completely clueless” when it comes to marketing their own country outside of the omnipresent all-inclusive resort brochures and TV spots.)

Is Scarborough even a world capital?

Before I go any further, you might be wondering how Scarborough even made it into a blog about world capitals. After all, Tobago isn’t an independent nation, but rather a part of Trinidad & Tobago, of which Port of Spain is the official (and only) capital recognized by the UN. It’s true that Scarborough isn’t technically a world capital, but I will be giving equal weight to both Port of Spain and Scarborough in my postings as I feel each are worthy of exploration and offer distinct and unique perspectives on what it means to be a Trini or Tobagonian respectively.

Tobago, which sits 35km (22 miles) northeast of Trinidad, is a fraction of its big brother’s size and has often been neglected and cast aside ever since their forced union by the British in 1889. Tobago is shaped like an oval and is only 40km (25 miles) long and 10km (6 miles) wide at its farthest points. There is an international airport on Tobago, but before Covid there was but one direct flight from New York and one from Germany each week. Most people fly to Port of Spain and then taken a propeller plane to Tobago; these flights operate 20 times a day in each direction and last a brief 22 minutes. There is also a four-hour ferry that drops you off in the downtown harbor area of each capital for $50TT ($7.50USD).

Trinidad’s economy relies heavily on exporting oil and natural gas that is mined off-shore in the Caribbean Sea. Port of Spain is full of hustle and bustle; a far more cosmopolitan city than Scarborough, where the vibe is decidedly more laidback and friendly. I was reprimanded by a woman on my first walk outside Hope Cottage when I merely smiled at her as I passed her on the sidewalk. “Excuse me,” she said in shock. “No one teach you no manners? Where you in such a rush?” I had committed the cardinal sin of not greeting a Tobagonian in public! “You say hello when you see someone. Fin’ out their day.” Yes, ma’am! Lesson learned!

English is the official language on both islands, but the people’s accents are markedly different and there are both distinctive Tobagonian and Trinidadian Creoles that are spoken on each island. (When two Tobagonians got rolling in creole, they might as well have been speaking Russian to these ears.) One phrase that carries over between the two islands is “limin’” which means chilling, hanging out (usually with a beer) and having a good time. Tobagonian Creole is wonderfully melodic and often hysterical. One of Len’s favorites was, “Who kill pries’?” (Who killed the priest?), meaning, who did something so terrible that you would give them such horrible advice? “Better belly bus’ than good food was’” means you better clean you plate whether at a restaurant or someone’s house. “Dog don’ make cat,” means children will take after their parents and “monkey know what tree to climb,” is commonly used to refer to someone knowing who to approach to get what they want.

For such a small island, Tobago has a rather varied ecological make up. Of the 60,000 residents, 18,000 of them call Scarborough home. Smaller towns line the highway that winds around the edge of the island, past bays, beaches and mangrove forests. The center of Tobago rises up from its (now dormant) volcanic peaks. The interior “Tobago Forest Preserve” is the oldest protected rainforest in the Western Hemisphere after conservation laws were handed down in 1776.

Ethnically, Trinidad is far more diverse than Tobago. The former has a sizable minority descended from Indian laborers, in addition to those born from African and European heritages, while Tobago is 85% Afro-Caribbean. Despite the short distance between the two islands, I got the sense that Tobagonians don’t make the crossing to Trinidad all that often, although Trinis will come to Tobago for a weekend getaway, staying in a village beachfront guest house.

Tobago Museum at Fort King George

Shamefully knowing very little of Tobago’s history, save for the fact that it was once a British colony, I made a beeline for the Tobago Museum, which is housed in the former barracks of Fort King George, a five-minute walk up the hill from Hope Cottage. The museum covers the island’s history from the time of the native Amerindians through the colonial era to independence and beyond. There is a large collection of Amerindian artifacts, pottery and adornos, or talisman. Three 800-year-old skeletons are on display that were excavated from ancient ruins on the north side of the island. There’s an original copy of John Poyntz’s 17th-Century pamphlet, “Pleasant Prospect of the Famous and Fertile Island of Tobago” that is believed to have been the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel, Robinson Crusoe.

Several groups of Amerindians ruled Tobago over the years before European invaders arrived in the 16th Century, at which time, the Kalina controlled the island. In 1511, the Spanish, who had established colonies on Hispaniola, decreed that they had “permission” to perform slave raids in Tobago, which continued until the 1620s, greatly decimating the Amerindian population. In 1628, the Dutch attempted to build a colony on Tobago, but the remaining native population drove them out. In 1641, King Charles I “gifted” the island to his godson, a Latvian duke, and thus Latvia’s first colony in the Caribbean was established. The Dutch and the Latvians wrestled for control of the island, with the former building a settlement called Lampsinsstad in 1658, that would later become Scarborough under British rule.

Between 1678 and 1814, Tobago changed hands a total of 33 times, more than any other island colony in the Caribbean. During this period, genocide was carried out against the remaining Amerindian people. By 1786, only 24 Amerindians remained and by 1815 the native population had been completely wiped out.

In 1763, the British gained control of Tobago and began bringing African slaves to work the sugar, cotton, indigo and rum plantations they had built all over the island. By the time Scarborough had been declared the colonial capital in 1779, over 3000 African slaves had been transported to Tobago. With no labor costs, the plantation owners grew immensely rich in a short amount of time. Within five years, 1.5 million pounds of cotton had been exported to North America and Europe. Slave uprisings were met with instigators being burned alive or having appendages amputated. Conditions were deplorable and slaves died faster than they could be brought over from Africa.

Fort King George

As tensions in the Caribbean were rising between the British and the French, Fort King George was constructed between 1777-79 on the highest peak overlooking Scarborough. Despite its excellent defensive position, the French were able to capture the fort in 1781, renaming it Fort Castries. Soon all of Tobago had fallen under French colonial control and Scarborough was likewise renamed Port Louis. The fort, which has been turned into an open-air museum, is one of the highlights of visiting the capital. The grounds contain the original jail cells, a powder magazine, bell tank, lighthouse, the Tobago Museum, the Icons of Tobago Museum, a Fine Arts Centre and the best views of Scarborough Harbor and southern Tobago.

The different sections of the fort are well-labeled and have info cards that will aid you on a self-guided tour. (Official guides are available for “free” guided tours- that will end in a compulsory tip- but don’t let them pressure you into walking around the heritage park by yourself, which you are perfectly free to do. Be aware that the museums do charge separate admissions, though.)

Imagine my surprise when I read the placard at the powder magazine, an addition to the fort under the French occupation, that explained how Fort Castries’ position overlooking Scarborough reminded the French of The Bock in Luxembourg City. The generals used Vauban’s revamping of those fortifications a century earlier as a guide for their expansion of their new stronghold here in Tobago. This may seem like a tiny detail to most visitors, but having just traveled to Luxembourg, I never would have guessed that I would be seeing connections from my previous adventure to this voyage in the Caribbean. The more you travel, the more interconnected you will find the world to be.

Of course, one of the main draws to visiting the heritage park is the view of of Southern Tobago; on a clear day you can see all the way to Trinidad’s mainland. Even though most of the park sits in direct sunlight, the breezes that swirl on the hilltop are refreshing and certainly beat the stifling afternoon heat in the downtown area below.

This small peninsula is Bacolet, Scarborough’s wealthiest suburb. Here you’ll find the fanciest residences, high-end shops and restaurants and a handful of boutique hotels. People looking to be pampered during their Tobago vacation, but still wanting to avoid the dreaded all-inclusive atmosphere, will likely look to Bacolet for some five-star rest and relaxation.

The lighthouse is one of the latest augmentations to the fort, having been transported from Trinidad to its current location in 1958. It can emit a beam that stretches 50km (31 miles) across the sea and is still used to guide ships during a storm.

The French also modernized the water systems throughout the fort when they built the bell tank in 1799. The well was connected to a series of pipes that collected rainwater from the roofs of nearby dwellings. The tank was designed to drain the sediment and debris carried in by the water, leaving the somewhat “purified” water to rest on top and be gathered and dispersed among the citizens and troops.

This one hurt. The Fine Arts Centre puts on contemporary art exhibitions by local Tobagonian artists throughout the year. The centre was closed for two weeks during my visit as the curators removed one exhibit and replaced it with another. Talk about bad timing. Caribbean top priority: return to Tobago for my contemporary art fix!

In 1793, the Brits retook the fort, but they still managed to pass it back and forth between the French until they cemented their control of the island in 1814. The British doubled down on the number of slaves they brought into Tobago until the African population reached 15,000 people. Slavery was outlawed in the UK in 1834, but even with their “freedom,” little changed for the African workers. They were now technically paid, but only received a pittance and most land was still owned and controlled by British plantation owners. Over the next decades, the sugar trade declined and the plantations were slowly abandoned. The descendants of the slaves, now the vast majority of those living on the island, turned to farming and fishing to make a living.

Low wages and limited access to land eventually led to the Belmanna Uprising in 1876, when the African population protested against the white colonialists who still controlled the local government. One of the officers killed a black protestor (sound familiar?) and chaos descended upon Tobago. The police station was surrounded and the chief was executed. The self-governing Legislative Council gave up control of the island in 1877 and in 1885, the British combined Tobago, Grenada, St. Vincent and St. Lucia into the Windward Island Crown Colony. Tobago still proved to be a thorn in the Brits’ side and a few years later, in 1889, the island was officially coupled with Trinidad. In 1899, Tobago was stripped of all sovereignty and made a “ward of the state” to Trinidad. It’s fate was no longer its own.

Tobago provided some contributions to national economy with its newfound lime, coconut and cocoa farms, but its citizens were continually afforded zero representation in the Trinidad Parliament. Finally, in 1927, Tobago was granted one seat in the legislative body, but the elections were very unfair. Only males aged 21 and above could vote and they had to pass both literacy tests and be landowners to cast a ballot. This rendered only 5.9% of the population eligible to vote and the frustrations with Trinidad continued to mount. James Biggart, a black Tobagonian, was the first person elected to fill Tobago’s seat in Parliament.

James Park and the Tobago House of Assembly

Along the winding road down from Fort King George to downtown Scarborough, you’ll come across James Park and the Tobago House of Assembly. The park is named after A.P.T James, who was elected to Tobago’s seat in 1946. Universal adult suffrage was introduced to the island during his tenure, as well as the construction of schools, health care facilities, a pipe line that would transport fresh drinking water and in 1952, electricity was brought to Tobago. James was an avid proponent of Tobago gaining full independence, a dream he never lived to see, and quite frankly not one shared by every Tobagonian. While some did support the cause, others simply longed for better representation and fair treatment from their more powerful neighbor.

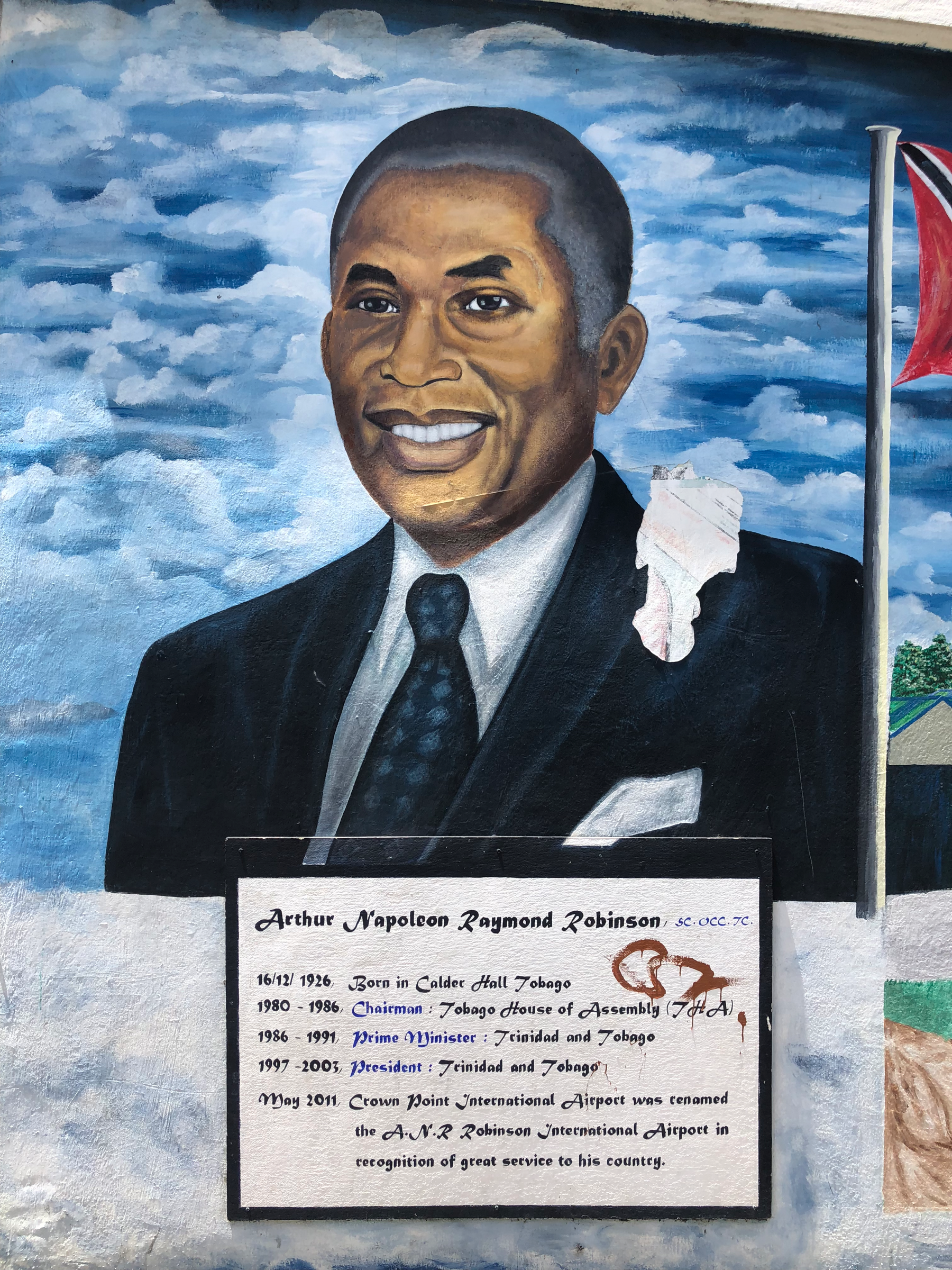

A.N.R. Robinson

In 1961, Tobago was granted two seats in Parliament (they currently have eight members in the legislature) and A.N.R. Robinson won the spot for Tobago East. At that time, only 5% of the federal budget was allocated for Tobago, a number Robinson tirelessly fought to raise. His other great mission was to restore much of Tobago’s sovereignty that was ceded to Trinidad in 1899. Success finally came in 1980 with the re-establishment of the House of Tobago, the island’s legislative body. Robinson resigned from Parliament and became the first Chairman of the House of Assembly for the next six years, after which he became the third Prime Minister of all of Trinidad & Tobago in 1986.

After facing defeat in 1991, Robinson ran for president in 1997 and won, making him the third president of the dual island nation. (Well, in truth, Trinidad & Tobago is made up of over 30 islands- some inhabited, some not- but Trinidad and Tobago are by far the largest.) He was responsible for creating Scarborough’s deep harbor in the 1990s and Tobago’s airport was renamed in the politician’s honor.

Ancil Dennis is the current Chairman of the House of Assembly, and when he was installed last year at 33 years old, he became the youngest person to lead Tobago. His opponents referred to him as a “child king” and “OJT” or on-the-job-trainee. Dennis has proven his critics wrong and enjoys popularity with the people as he has been forced to navigate his way through the Covid Era.

The Roads of Scarborough

Fair warning: Scarborough will kick your ass, or at least finely shape it! There is barely a flat section of road to be found in the capital. The city hugs its semi-circular harbor and then steeply rises back like a horseshoe-shaped stadium or amphitheater. Walking down the hills, I felt as if I were about to tumble forward at any moment; trudging back up again in the heat of the day was even worse. Cars notoriously make it halfway up Main Street and either stall out or roll right back down the hill again!

On my first night in town, I had a great time downtown drinking beer, eating doubles (local cuisine that is to die for) and even topped my revelry off with two scoops of ice cream. It suddenly hit me that Hope Cottage was 3/4 of the way up the sides of the city and I had no idea how I was going to make it back. Halfway up, the delirium must have set in. I don’t remember how I got back to my room, but I did wake up in my bed safe and sound.

Street Art in Scarborough

This fantastic mural that runs alongside the road beneath the Botanical Garden, takes you on a colorful whirlwind of the history and culture of Tobago. A few notable figures I’ll point out are Bertille St. Clair and Dwight Yorke, Tobago’s most celebrated football coach and player, respectively. Like so much of the world, football (soccer for Americans), is the dominant sport in Tobago, although cricket and goat racing- yes, goat racing!- are also popular.

Shurwayne Winchester is one of the best-known Soca singers in the Caribbean. Soca, which stands for the Soul of Calypso and African Music, originated in Trinidad & Tobago in the 1970s. A group of local musicians felt that calypso music was under appreciated and had fallen out of favor with young people in favor of reggae, funk and soul. Soca sprang forth as kind of a new wave calypso that has remained wildly popular on the islands ever since.

The Icons of Tobago Museum back at Fort King George has a fantastic exhibition on Calypso Rose, the grand matron of Tobagonian Calypso/Soca music. Born in 1940 on Tobago, Calypso Rose has composed over 1000 songs and recorded more than 20 albums of music. At age 81 she’s still going strong, writing and recording to this day. She was never afraid to tackle social issues in her music, using her platform to combat racism and sexism in the Caribbean. Although she frequently returns to perform in Trinidad & Tobago, Calypso Rose lives right across the river from me in Queens, NYC.

Burnett (or Burnette) Street is a fun thoroughfare to explore. Here you’ll find thrift stores, antiques, knickknacks, used clothes and more. The advert for Just My Size also gives you an idea of how people give addresses in Tobago. Instead of, “Go to 215 Burnett Street,” you’re more like to hear, “Go to that store that sells costume jewelry and handbags. You know the one, right behind Crusoe’s Bakery at the bottom of Burnett Street.” Landmarks will always trump numbered addresses.

Botanical Garden

Nestled in the heart of Scarborough and spread out over 18 acres that once acted as a sugar plantation during colonial times, the Botanical Garden is a relaxing spot to check out Tobago’s flora. Now, if you’ve been following this blog for some time and were paying attention to the flower photos I posted from Ghana, Togo and Benin, you’re about to experience some déjà vu. Seeds and plants native to West Africa were also brought to the Caribbean with the slave ships, creating an Afro-Caribbean ecology that matches the inhabitants of the islands today. African tulips bloom next to samen, or monkey pod trees, which are native to Central American and the Caribbean.

Scarborough Esplanade

The Esplanade is Scarborough’s newest attraction: a series of vendor huts that sell food and souvenirs throughout the evening. This picturesque path along the harbor is prime limin’ territory; everyone will be ready to hear your life story and share theirs in return. The views of the Port of Scarborough all the way up to Fort King George are stunning.

As I begin to wind down my overview of Scarborough, Tobagonian history and the harmful nature of all-inclusive resorts, I have come to realize that travel is a repetitious cycle of having your preconceived notions of a destination continually dismantled and re-evaluated. Why was I so hesitant to visit the Caribbean? Did I actually think I wouldn’t find an engaging history and culture here to explore? Why did I allow myself to be so influenced by travel books and tourism boards? Whatever I think I know about a country/capital is wrong. At least it lit a fire under my feet to dispel these stereotypes about Caribbean travel; even if I’m just one voice yelling into the wind, I hope someone will hear me.

La ville riche avec plan de souvenir

Merci, Scarborough est vraiment une ville merveilleuse avec une grande histoire et culture.