“It’s delimit, it’s deluxe, it’s de-lovely!”

As far as I know, Cole Porter didn’t have Luxembourg on the brain when he wrote those lyrics, but he might as well have. Luxembourg City is impossibly charming and picturesque, so much so that parts of the capital appear to have been built simply so one could take postcard-worthy photos of the plateaus and valleys that constitute the landscape.

I’ve spent the last dozen or so posts dismantling the stereotypes of Amsterdam and Brussels, my first two stops through the Benelux capitals. Amsterdam is all drugs, hippies and prostitutes, right? No way! There’s art, history, architecture and culture galore! Brussels is a stodgy city filled with dull government workers and EU diplomats, right? No way! There’s art, history, architecture and culture galore! And what of Luxembourg City? All those stereotypes about it being an ultra-expensive desitination that could break even the highest of budgets? Well…ok, this stereotype is true and there’s really no way around. There is great art, history, architecture and culture, but it’s going to cost you.

Even Luxembourg’s name forewarns of its grandeur; some countries are nations, republics or even kingdoms, but Luxembourg has to go and be a Grand Duchy for Christ’s sake. Luxembourg even has “luxe” as its opening syllable, alerting the world to what you’ll find in this teacup-sized country. (Etymology experts, relax. I know that Luxembourg derives its name from “little castle,” a rather ironic name seeing as Luxembourg City had one of Europe’s largest medieval fortifications, but Luxembourg today has become more synonymous with luxury than the remains of its former defenses.)

Throughout these posts, I’ll try to give a few tips on ways to save money throughout the country, but in reality, your efforts will be futile. This is not a budget-friendly destination and its solitary, poorly-reviewed hostel in the capital doesn’t do Luxembourg’s reputation any favors either. (I stayed in this hostel on a previous visit to Luxembourg in 2001 and it was enough to make me seek refuge in an Airbnb this time around. It’s a bummer for me to miss out on the hostel experience, but I enjoyed getting to know my two Italian hosts who had moved to Luxembourg City several years ago owing to their jobs in the financial sector.)

Despite the damage Luxembourg will wreak on your wallet, its beguiling nature is undeniable. (Note: Technically the capital of Luxembourg is simply “Luxembourg,” but to clear up any confusion, it is often referred to as Luxembourg City to differentiate between the city and the country. I will use them interchangeably, but will also attempt to make it clear when I’m discussing the entire nation or just the capital city.)

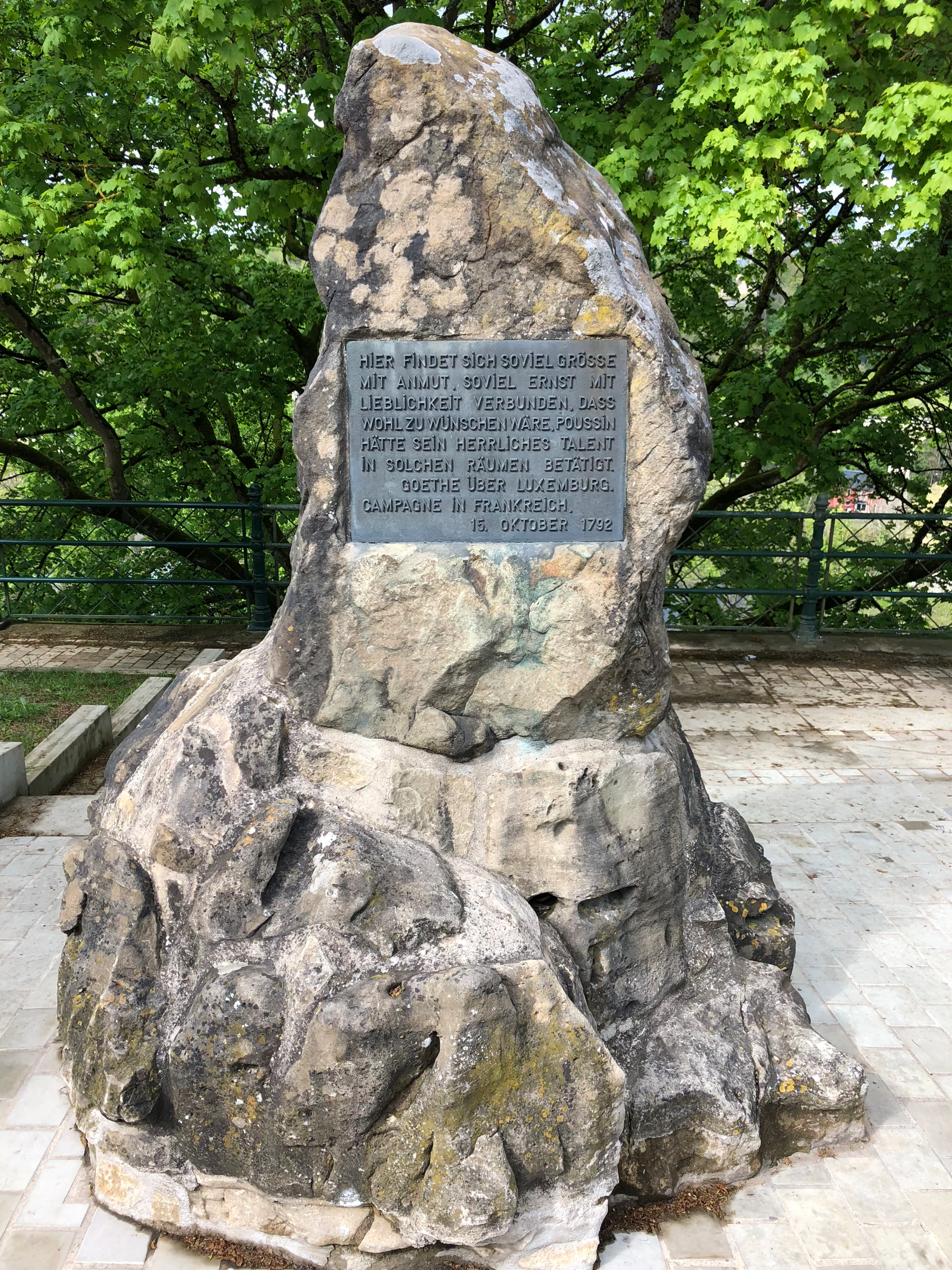

The Goethe Memorial was erected in 1935 to commemorate Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s love for the city. One of Luxembourg’s earliest tourists, Goethe returned to the Grand Duchy for the second time in 1792, after which he penned the following: Hier findet sich soviel Größe mit Anmut, soviel Ernst mit Lieblichkeit verbunden, dass wohl zu wünschen wäre, Poussin hätte sein herrliches Talent in solchen Räumen betätigt. (There is so much greatness and grace here, so much gravity combined with gentleness, that one wishes Poussin had employed his wonderful talent in such an environment.) UNESCO agrees with Goethe; in 1994, the remains of the fortifications, including 17km (10.5 miles) of underground tunnels, as well as the entirety of the old town quarters, were deemed a World Heritage Site and carry a protected status. Luxembourg City has been so well-preserved that it wasn‘t just a church, castle or town square that caught UNESCO’s eye, but the whole central metropolis!

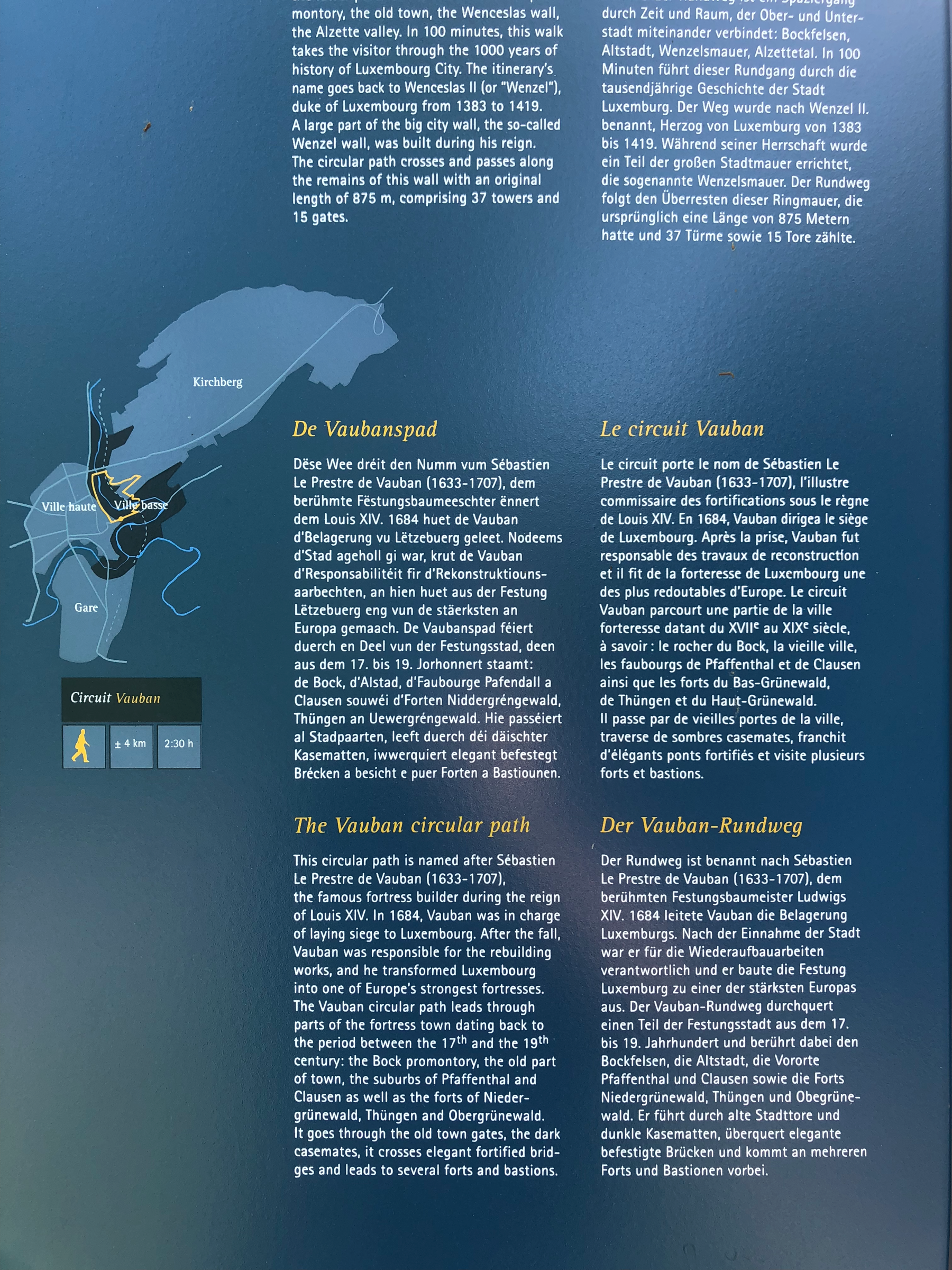

Luxembourg has a high degree of tourism infrastructure. Walking paths with informational signage are well-marked throughout the city. If you thought Brussels having two official languages (with the addition of English often being included) was a lot, Luxembourg has three official languages: French, German and Luxembourigsh, or Lëtzebuergesch in Luxembourgish. The capital is truly an international city, with 70% of the population comprised of immigrants from 160 different countries. Because of this, English has become a de facto official language and you will most likely be greeted in English before any other language. Once you leave Luxembourg City, this will not be the case. I made two day trips on my visit, and to the east I encountered German and Luxembourgish and to the north everyone spoke French. You will receive major brownie points if you greet a museum or shop worker in Luxembourgish; you can pick up an English-Luxembourgish dictionary at the tourist info center near the town hall.

The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is one of the world’s smaller nations, ranking 168th in area at 2586 sq km (998 sq miles). Luxembourg may be pint-sized, but it enjoys strong diplomatic relations with the rest of the world; its citizens are privy to one the most powerful passports, granting them access to 187 countries visa-free or visa-on-arrival. The capital’s population sits at 115,000 people, but there are 170,000 registered jobs in the city. This means that 55,000 commute into and out of the city everyday, often internationally from Belgium, France and Germany. As you can imagine, traffic is horrendous and in March 2020, Luxembourg became the first country in the world to offer completely free public transportation in the entire country for citizens and visitors alike. All buses, trams and trains (save for 1st Class train cars) are completely free to ride within Luxembourg’s borders. The hope is that this will cut down on people driving their own vehicles into the city and alleviating congestion. (If you’ll recall, Tallinn’s public transportation is also free, but it extends neither to the rest of Estonia nor to non-residents of the capital.)

Lëtzebuerg City Museum

If there’s one thing you can do to ease the financial burden of visiting Luxembourg, it’s to purchase a Luxembourg Card. You can buy one at any tourist info center or train station in the country and it grants you entrance to 79 museums, castles, parks and other attractions throughout the Grand Duchy. If you only plan on visiting one museum or one historical site, then the card probably isn’t worth it, but if you’re like me and are never sated by a city’s cultural offerings, then don’t think twice about picking one up.

Did your education somehow bypass its unit on Luxembourgish history? Never fear, the Lëtzebuerg City Museum is here. The permanent exhibition, dubbed “The Luxembourg Story” gives a detailed account of Luxembourg’s turbulent history through medieval times to its role as a founding member of the EU before ultimately becoming a banking center that rivals Switzerland in the 21st Century.

Luxembourg’s castle’s earliest mention dates back to 963 AD, after which the kingdom’s power and area continued to expand until it reached its zenith when Henry VII, Count of Luxembourg, ascended to Holy Roman Emperor in 1312. Luxembourg remained one of Europe’s most formidable powers for over 100 years until the city’s fortress fell to the Spanish in 1443 and the once independent nation was absorbed into the Spanish Netherlands, followed by the Austrian Netherlands, then became one of the 17 Provinces, bullied into fighting for Dutch independence until Napoleon conquered the region and Luxembourg was forced under French control.

After Napoleon’s defeat, the Congress of Vienna reorganized Europe in 1815, and Luxembourg was officially handed over to The Netherlands. After Belgium gained independence in 1830, Luxembourg had one more battle to fight in 1839 to achieve its own independence from Belgium. The borders that were established in 1839 are the borders that still define Luxembourg today.

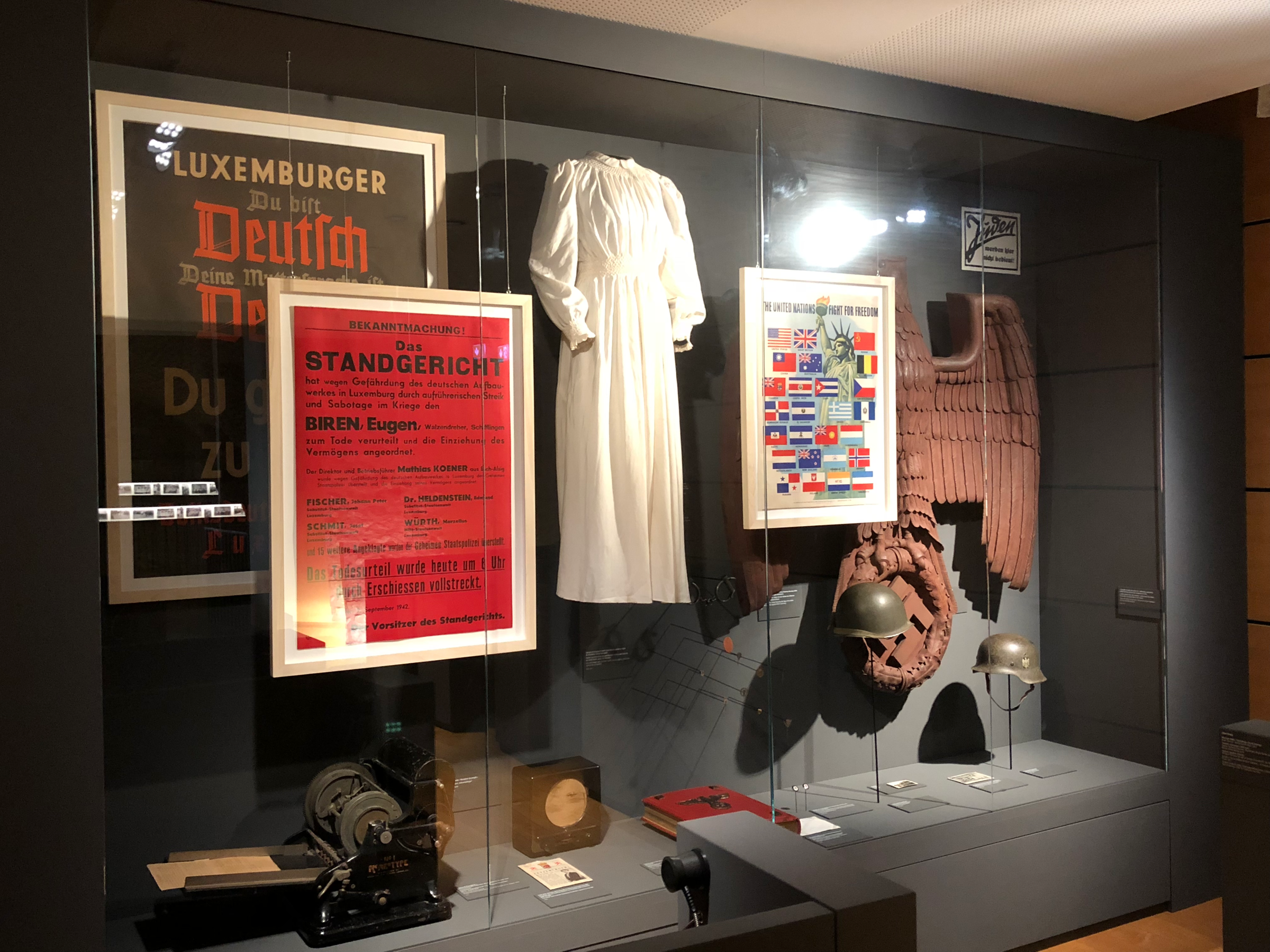

I will be devoting a later post to Luxembourg’s role in World War II and the Luxembourgish Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust, but for a brief overview, the Nazi Army captured the city on May 10, 1940 and an aggressive campaign ensued to wipe out all traces of the Jewish community, as well as to convert the non-Jewish Luxembourgish population into German citizens. French and Luxembourgish were forbidden to be spoken in public and all young men were drafted and sent to the Eastern front to fight against the Soviet Union. A resistance, known as the Red Lions, brewed underground and sought to undermine the Nazis at every turn, including smuggling Jews to the countryside where they could be hidden in churches and farms. Luxembourg was liberated on September 10, 1944 and has worked to establish strong bonds with its neighbors ever since.

After the Nazis tried to stamp out the Luxembourgish identity in the early 1940s, post-war Luxembourg focused on re-establishing a cultural sense of self. Locally produced products were subsidized by the government and tourism was promoted throughout the continent. The museum has a fantastic collection of posters featuring Luxembourgish goods and services from the 1950s that bolstered both industry and national pride.

In 1957, Luxembourg joined The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy and West Germany as one of the founding members of the organization that would later evolve into becoming the European Union. The EU’s Parliament is in Brussels, but all of financial institutions that fund the EU are located in Luxembourg City. The exhibit features some straight-out-of-Star-Trek models of proposed EU headquarters that were never realized.

Despite nurturing a modest steel industry, it was clear that Luxembourg was never going to become a manufacturing powerhouse and eventually the government turned to high-finance and banking to generate income. 152 nations have situated a branch of their national banking system within Luxembourg’s borders, where its tax-haven status continues to stimulate the economy and rank Luxembourg in the top three highest per capita GDP earners worldwide.

Nationalmusée fir Geschicht a Konscht/Musée national d’histoire et d’art/Nationalmuseum für Geschichte und Kunst (National Museum of History and Art)

It’s really a workout to list all three official titles of the National Museum, but I did so out of linguistic interest to demonstrate how Luxembourgish has evolved alongside French and German, borrowing heavily from both languages, including accents and umlauts. If you can read German and/or French, even passably, then it can be quite easy to pick up on the other languages after seeing so many iterations of a translated text.

The National Museum was far less interesting than the Lëtzebuerg City Museum, and if I hadn’t gained free admission with Luxembourg Card, I would have been sorry I spent money on the entrance fee, although your personal mileage may vary. I was impressed with the massive mosaic dating from 240 AD found in a villa in the city of Vichten from Roman times. The tiles were transported in small chunks to the museum and reassembled in this space expressly built for the mosaic in 2002.

The rest of the museum is rather dry and stuffy, focusing on the archeological finds from the Roman era and Luxembourgish fine art from the 14th through the early-20th Centuries. It’s all tastefully displayed, but did little to light a fire inside of me. The history was far more engaging in the Lëtzebuerg City Museum and there is much more exciting art happening elsewhere in the capital.

Musée Dräi Eechelen (This one you’re only getting in Lëtzebuergesch!)

Across the Alzette River Valley, Fort Thüngen was built between 1732-33 and was nicknamed Dräi Eechelen, or Three Acorns, due to the little stems placed at the top of the fort’s three towers. Fort Thüngen was used by the Habsburg Army during Luxembourg’s stint in the Austrian Netherlands, until it was largely pulled apart in 1867 after a treaty was signed in London that further secured Luxembourg’s sovereignty and in return the government had to willing dismantle portions of the city’s fabled defenses.

For most of the 20th Century, only the three towers and a portion of the fort’s out wall remained intact. In the 1990s, restoration efforts began to rebuild the pieces of the fort that were demolished in 1867. Photographs and artistic renderings allowed historians and architects alike plenty of material with which to work, and Fort Thüngen now stands as it once did before its forced demise. Since 2012, the fort has been turned into a museum which displays 600 artifacts from medieval times until 1903, when the Adolphe Bridge was completed, connecting the old town with its ever-expanding modern suburbs.

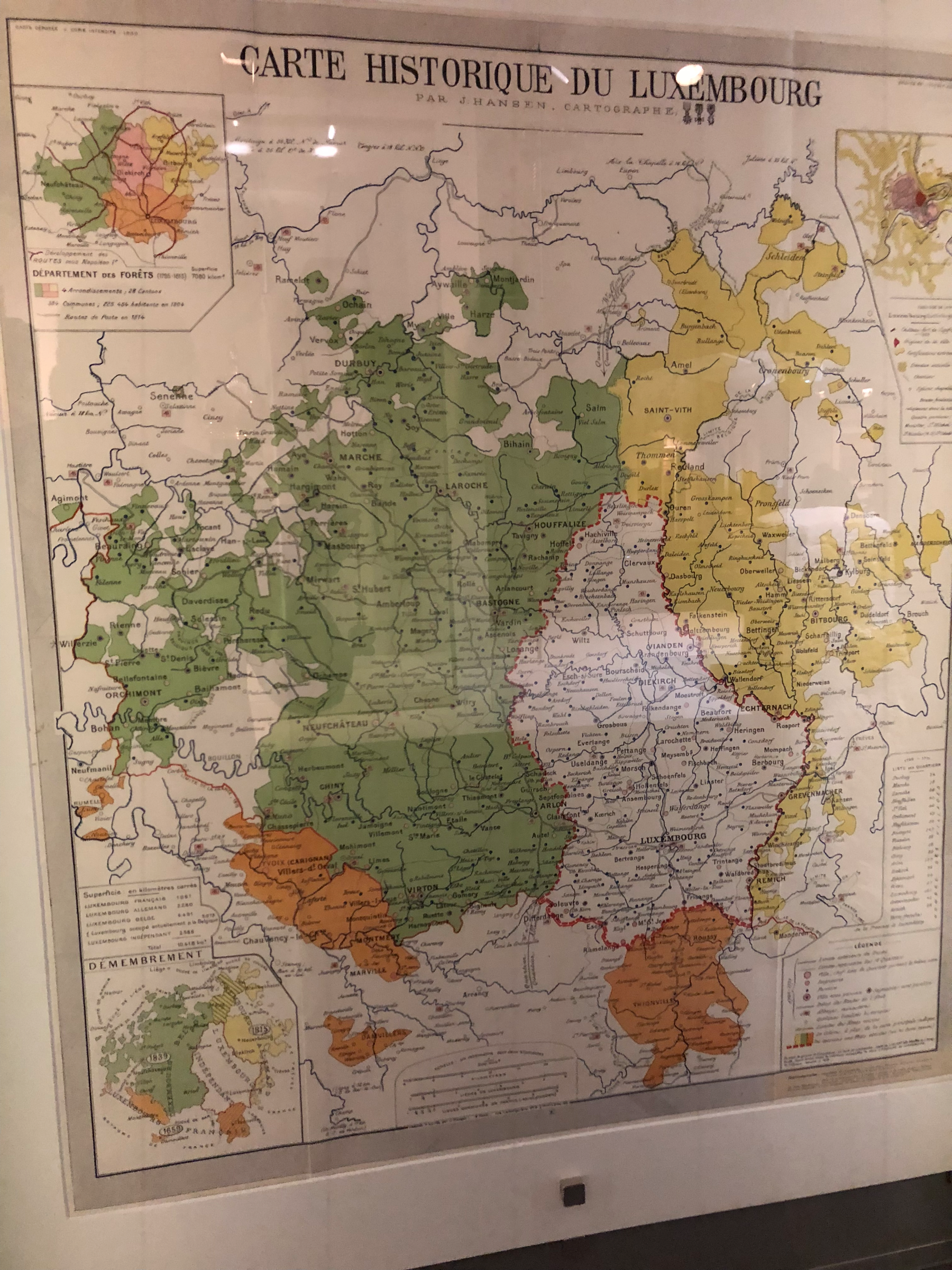

To give you an idea just how vast and powerful Luxembourg once was, this map in the museum shows all the territory that once belonged to Luxembourg. In 1659, the yellow-shaded area was lost to Germany; the orange bits were then ceded to France; the greatest loss was the green region given to Belgium in 1839 to secure their independence. Small pockets of Luxembourgish speakers can still be found in Germany, France and Belgium today.

Fort Obergrünewald/Fort Niedergrünewald

Below the Musée Dräi Eechelen you’ll find the ruins of two medieval forts that provide some of the best views of the Old Town from across the Alzette Valley. Unlike the hiking trails around the city center, these two forts are largely devoid of visitors, allowing you some one on one time with the city’s history. If anything, you’ll encounter locals who’ve brought some sandwiches and beer to sunbathe on the grassy knolls and take in their city from afar.

Knuedler/Place Guillaume II

Of course, you don’t have to limit your history lessons to museum exhibitions, especially when the city government of Luxembourg has gone to such great lengths to post info cards detailing the significance of its monuments and memorials across town. Take, for example, the equestrian statute of William II in Place Guillaume II, or Knuedler as it’s known in Luxembourgish slang, referring to the knots Franciscan monks tie around their robes. This central square was once home to a monastery that Napoleon destroyed upon his invasion of Luxembourg in 1795. After Napoleon’s defeat, William I was made King of Netherlands and Grand Duke of Luxembourg, ensuring that the Grand Duchy remained nominally under the Dutch monarchy’s control, even after Luxembourg gained full independence in 1839.

By this time, William II had ascended to the throne and placed his likeness in the square, much to the chagrin of the Luxembourgers. The Netherlands, Belgium, France and Germany all feared Luxembourg’s fortress would fall under one of the other’s power. To avoid a conflict and grant Luxembourg more autonomy, the fortress was largely deconstructed, brick by brick, and Luxembourg lost its allure as a military stronghold. Finally, in 1890, Luxembourg established its own royal lineage, breaking with the Dutch once and for all. It was during this period that the Luxembourgish saying, “Mir wëlle bleiwe wat mir sinn” (We want to stay what we are) became the official National Motto.

Today the square is famous for its annual summer festival, “Rock um Knuedler,” which host rock bands from around the globe and attracts over 10,000 music enthusiasts. This is a good time to you (and myself!) to also check a city’s festival calendar before booking a trip. Maybe you want to visit during a film festival, or perhaps you want to specifically avoid a time when accommodations are fully-booked and a city might be more crowded than usual.

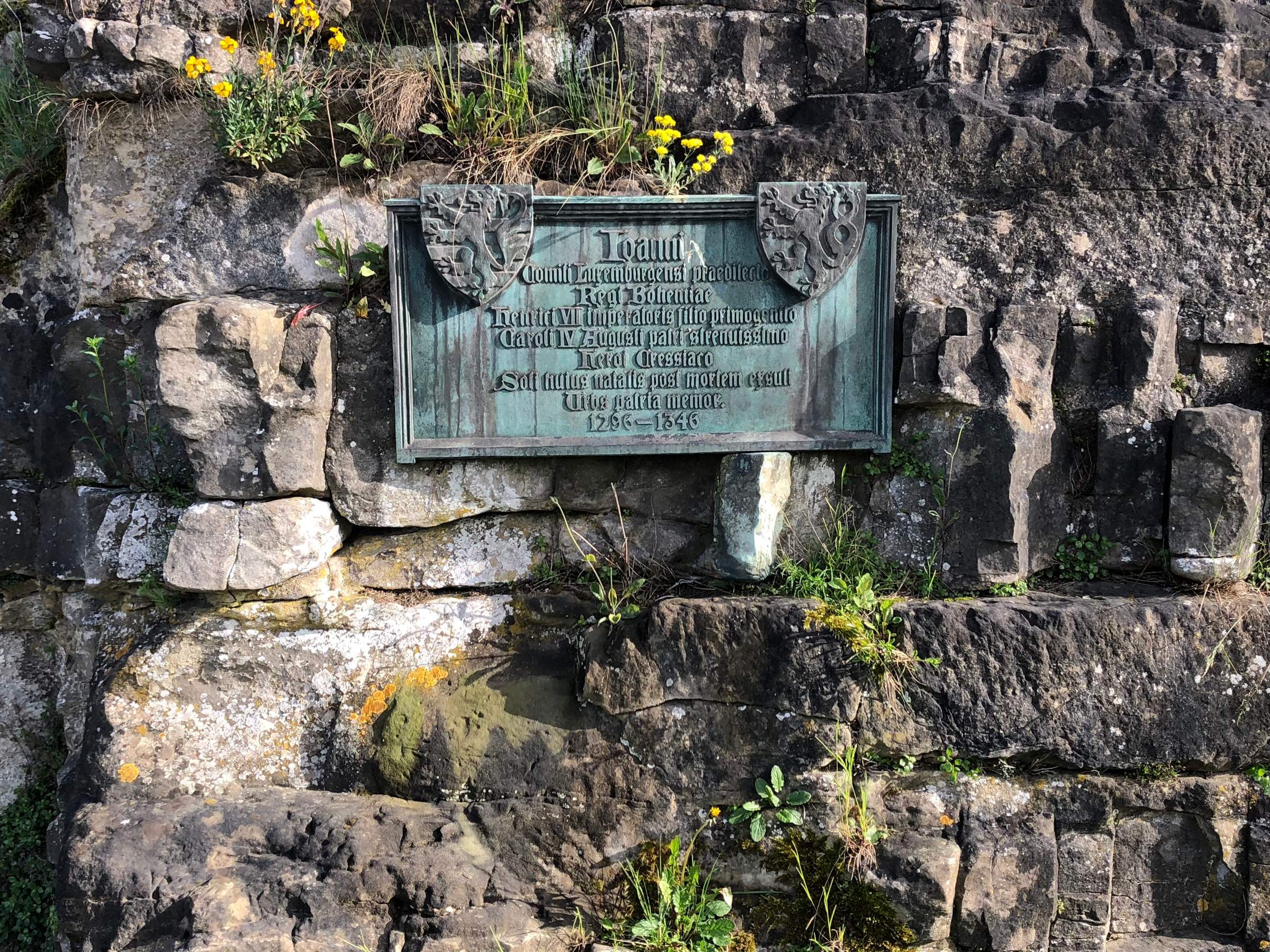

John the Blind

Of all the historical leaders that governed Luxembourg during the Middle Ages, the most popular in modern folklore is John the Blind, who became both a Count of Luxembourg and the King of Bohemia during his reign. Although he suffered from a degenerative ocular condition, completely losing his sight by age 40, John continued to fight in battle for his kingdom. How much of this is myth and how much is truth is difficult to tell, but mementos of his bravery are scattered throughout the city.

Gëlle Fra (Golden Lady)/Monument of Remembrance

The Monument of Remembrance, which is topped with Gëlle Fra, has a history shrouded with mystery and intrigue. This memorial was originally erected in 1923 as a way to honor the Luxembourgers who died fighting the German Army in World War I. When the Nazis invaded Luxembourg City in 1940, one of the first things they did was knock down the monument and leave the pieces in Constitution Square where brave citizens snatched up the hunks of stone and stored them in their homes until the war was over.

In the years following World War II, every bit of stone and bronze was miraculously accounted for, except for the Gëlle Fra. Perhaps the Nazis had made off with her or an unscrupulous Luxembourger was keeping her all to him or herself. Decades passed, until one day in 1980, maintenance began on the city football stadium. Lo and behold, Gëlle Fra was found half buried under one of the stadium bleachers! Over the next five years, the monument was expanded to not only honor those who died in WWI, but also those who perished in WWII and the Korean War. The cherry on top was finally reuniting Gëlle Fra with her base upon its re-unveiling in 1985.

Luxembourg may be an expensive city to visit, but don’t let that high cost be the only thing that defines your perception of the Grand Duchy. Likewise, don’t be fooled into thinking the picturesque setting equates to a sedate experience. The swirl of languages, cultures and dramatic history have melded themselves into an international city that remains decidedly Luxembourgish, filled with a quirky people who seem genuinely welcoming to guests. Expensive doesn’t have to mean snobby or elitist, even those these attributes often become conflated with one another. There’s still plenty of art, history, architecture and culture to enjoy. Just remember to close your eyes at checkout.

Un pays prient d’histoire et de belle image

Merci, mon ami.