The Dutch, like so many European peoples, have a history that is anything but straightforward. Before 1830, The Netherlands and its current borders didn’t even exist. The region’s early history is a tangled web of land changing hands and various feudal city-states rising and falling over the centuries. It’s easy to get bogged down in the minutiae of the power plays involving the Spanish, French, German, Austro-Hungarian and British conquerors of the “Low Countries,” as The Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg were collectively known in those days. (17% of The Netherlands is below sea level and another 50% of the nation is less than one meter above sea level.) Luckily for the traveler, there are some excellent and often neglected history museums in Amsterdam that will aid you in untangling this mess, if you so choose to undertake the endeavor!

Amsterdam Museum

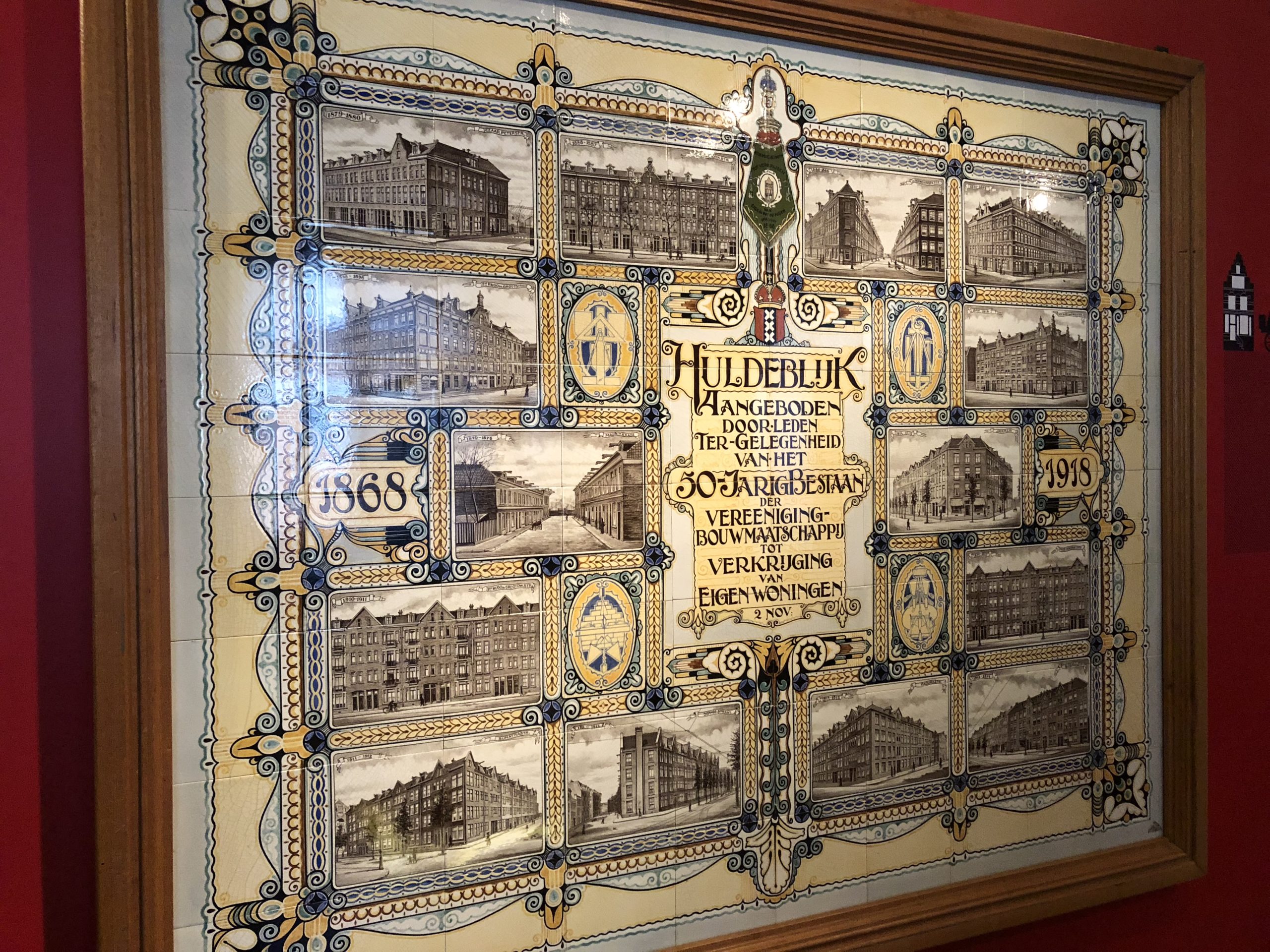

Established in 1975, the Amsterdam Museum (museum is the same word in English and Dutch, so you’ll never have trouble figuring out where these institutions are in the city), features sprawling exhibits that chronicle the 1000-year history of the Dutch capital from its humble beginnings as a fishing village to the international city it is today. The building itself was once the Amsterdam Orphanage, which saw thousands of children pass through its doors between 1850 and 1960 when it finally closed. Most people run straight to the Van Gogh or Rijksmuseum (for the Rembrandts), but I rather suggest beginning your exploration of Amsterdam at its namesake museum where you can establish a baseline of Dutch history.

Settlers appeared on the marshy plains of Amsterdam in the late 10th Century, but it wasn’t until a dam was built across the River Amstel in 1173 that the city conjured up its name and began to flourish as a trading post. To really understand Dutch history, we have to go back a little further to 800 when Charlemagne was crowned the first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He expanded the empire’s territory greatly, but when he died, the kingdom was divided evenly between his three grandsons: the western chunk became modern day France, the eastern piece is now Germany and the middle strip encapsulated The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Northern Italy. Due to a variety of factors, France and Germany grew into European super powers and the lowly Low Countries were caught in between, often traded back and forth as the spoils of war dictated.

My advice? Don’t get hung up on the various kings and queens who ceded power just as quickly as they had gained it in the Middle Ages. The museum does a good job of not overwhelming the visitor with, “In 1467, King Philip the Good of Burgundy died and his son, Charles the Bold, took the throne before being killed in battle ten years later.” I have always felt that details like these are what turn people off from learning about (and retaining) history. The repetitive nature of the timeline becomes monotonous and these historical figures certainly don’t have the same effect on modern Dutch life the way the events of World War II and the counter-culture of the 1960s still ripple into the present. Still, I’m glad I brought up Philip the Good, because he was the first ruler to attempt to unify the various counties and minor kingdoms of the Lower Countries into a cohesive nation of states. The experiment was short-lived, but it laid the blueprints for The Netherlands’ future.

The Low Countries eventually fell under Spain’s control, and in 1549 King Charles V once again took another stab at uniting the region into the so-called “Seventeen Provinces,” which held all three present-day Benelux nations. Charles’ reasons were far from altruistic: he wanted the assortment of fiefdoms to be organized so he could more easily tax the people and convert them to Catholicism. (Protestantism, and in particular Calvinism, had taken a foothold with the Dutch, and Spain was eager to stamp it out.) King Charles V was succeeded by Phillip II, who launched the Eighty Years War (sometimes known as the Dutch War of Independence) against the Seventeen Provinces after Dutch Protestants smashed Catholic statues throughout the region in 1566. Phillip responded by slaughtering 18,000 Protestants accused in connection with the crimes, and the fight for liberation had begun.

In 1581, in the midst of the war, the northern provinces declared their independence from Spain and formed the first Dutch Republic. Although not formally recognized by all European powers until a treaty was signed to end the war in 1648, the Dutch had declared themselves a unique people and the Dutch Golden Age had begun. Amsterdam in particular saw a mighty boom in the 17th Century. The Grachtengordel, or rings of canals that have since trademarked the city, were built. The world’s oldest Stock Exchange was founded in 1609, as well as the Dutch East India company, which catapulted Amsterdam to the rank of wealthiest city in Europe at the time. After the religious persecution inflicted by the city’s former Spanish occupiers, Amsterdam became a center for religious tolerance and acceptance. A large Jewish community formed (1/10 of the population was Jewish by the onset of the World War II) and Protestants of every stripe flooded the city. Today, The Netherlands is one of the most secular countries in the world, with only 17% of the population saying they hold any religious beliefs.

And yet, I was not able to uncritically admire the Dutch for their great successes during their “Golden Age.” My latest trip to West Africa had exposed the extent to which Dutch wealth was earned by participating in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade during this era. As I continue to travel more and more, I can’t just see each trip as an isolated visit. You begin to see the economic connections throughout history on a global scale. The Dutch, who had just lost 100,000 lives in their fight against Spain for independence, turned around and built a good deal of their empire on selling African slaves in the New World. The Dutch also colonized Indonesia, building plantations that exported coffee and spices back to Europe and used the local population for labor under deplorable conditions. This “Golden Age” for some, was an age of terror for others.

The Golden Age came to an end in the 1800s when Napoleon invaded the Dutch Republic and absorbed it into France. After Napoleon’s defeat, The Netherlands, which basically was comprised of the entire Benelux region, declared independence (again) in 1815. Fifteen years later, in 1830, Belgium broke away from its northern half and the borders of The Netherlands as we know them today were codified. The Dutch created a constitutional monarchy, that, much like their British counterparts, still exist, but with very limited political power. The Netherlands was able to remain neutral in World War I, but it fell within four days to the Nazi Army in World War II; I’ll discuss this period later on in the post when I visited the Verzetsmuseum (Resistance Museum) and the Historic Jewish Quarter.

Post-World-War-II Amsterdam was the nexus for the counter-culture that dominated Dutch society in the 1960s and 70s. Sexual liberation and drug use intertwined with political activism and efforts to preserve the environment. One of my favorite exhibitions at the Amsterdam Museum about this period dealt with the Witkar program, a fleet of electric cars that were supposed to encourage carpooling, in turn reducing carbon emissions and alleviating traffic congestation in the capital. Sadly, the cars had difficulty retaining their charges, causing the program to be phased out in 1986. Although Witkars never fully caught on, at least efforts were being made to better urban life in environmentally-friendly ways.

Always one to be ahead of the curve and a leader in human rights and equality on a global scale, The Netherlands became the first country to legalize gay marriage, with the first ceremony taking place on April 1, 2001. The gay community plays a large role in Amsterdam’s identity. The city is known for having one of the most-attended gay pride celebrations in the world, and society, as a whole, is exceedingly open and accepting of gay individuals. Despite its messy past, after reading about all the protections currently afforded to workers, women, LGBT people and other groups, it was difficult not to see The Netherlands as a utopia among nations.

Nationaal Monument

Not far from the Amsterdam Museum is Dam, the central square and meeting spot in the capital. There are several historical points of interests on or near square, including the Koninklijk Paleis (Royal Palace), forming the western border, and the Nationaal Monument on the eastern edge. The 22m (72ft) monument was erected in 1956 to commemorate the Dutch loss of life in World War II. The figures represent the resistance movements by both the intelligentsia and the working classes, with the highest-placed woman symbolizing peacetime after the war. The back wall of the monument contains 11 urns of soil from different areas in the country where large numbers of Dutch citizens were killed by the invading Nazi army.

During the 60’s and 70’s, the counter-culture co-opted the monument as their symbol of liberty. Hundreds of hippies began camping out and sleeping around the monument each evening. Riots ensued after the mayor banned sleeping on the square and clashes with the police set off investigations into police brutality. Today, seemingly every walking tour of Amsterdam will begin and end at the monument and the square is a great place to gather your bearings before venturing out into the Grachtengordel.

Koninklijk Paleis (Royal Palace)

The Koninklijk Paleis originally began life as Amsterdam’s Town Hall when it was built during the city’s Golden Age in 1648. When Napoleon conquered the Low Countries, the building caught his eye and he bestowed it to his brother as a royal residence while he governed the region. Napoleon’s reign was short-lived, but it wasn’t until 1936 that the palace was handed over to the Dutch monarchy as one of their three permanent residences. When not being used for official state functions, the palace is open to the public for self-guided tours. Tickets are cheaper if purchased ahead of time online (and you get to skip the line at the door). The audio guide is a bit stale and drones on a minute too long in each room, but it’s included in the price of the ticket so you might as well grab one upon entering the building.

The real star of the show is the architecture, a model of 17th-Century Dutch classicism. The palace underwent extensive renovations from 2005-09, restoring the interiors back to tip-top shape. The 21 rooms open to the public will take you no more than an hour to see; I was told the afternoon crowds can be rather overwhelming, so best to schedule your visit sometime before lunch. I’m usually more at home in a modern art space than a royal palace, but sometimes I can really be gobsmacked by the opulence of another era.

Plantage (Jewish Cultural Quarter)

Although it is filled with somber memorials to the atrocities of the Holocaust, one of my favorite neighborhoods to visit in Amsterdam was the Plantage. A product of the expansion of canals during the Golden Age, this section of the city became known for its gardens, parks and theater district; it still houses the botanical garden and national zoo today. Over time, Amsterdam’s Jewish population settled in the Plantage. Synagogues, Hebrew schools and Jewish markets began to fill the streets. You can pick up a map at the Joods Historisch Museum (Jewish Historical Museum) that is marked with a 90-minute walking tour of important cultural points of interest across the Plantage. (Especially not to be missed is the daily flea market on Waterlooplein. Once the site of the largest Jewish market in Amsterdam, the flea market is the cheapest place in the city to buy t-shirts, souvenirs and other assorted bric-a-brac.)

A ticket to the museum will grant you access to five different Jewish cultural sites around the Plantage and the ticket is valid for one month. If you’re spending more than a few days in Amsterdam, this offers you the chance to delve into Jewish history without feeling the pressure to visit each museum and historical site in a single afternoon.

Joods Historisch Museum (Jewish Historical Museum)

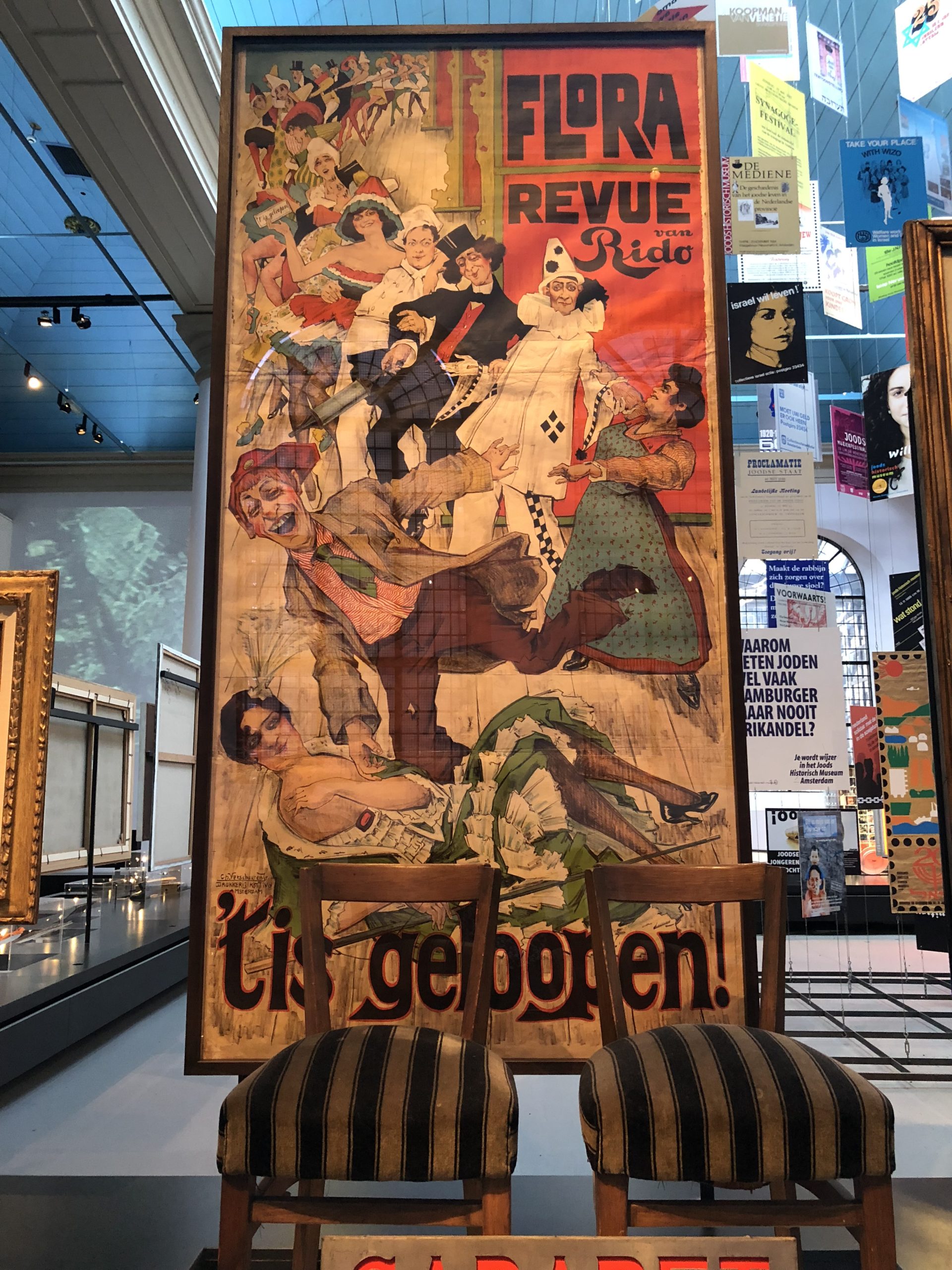

Sometimes when we think about Jewish history, the only subject that comes to mind is the Holocaust, but Jewish heritage is, of course, not defined by a single dark chapter of its long history. The Joods Historisch Museum touches on the Holocaust, but is more concerned with examining Dutch-Jewish identity. My love of live theater caused the exhibits about the strong ties between the arts and the Jewish community to hold a particular interest for me. Before World War II, a majority of the city’s theaters were run by Jews; the Jewish cabarets and comedy revues were an integral part of Dutch nightlife as well.

Religious freedom laws from the 17th-Century attracted large numbers of Jews to Amsterdam to avoid the persecution they experienced in other parts of Europe. Eventually the Dutch capital became known as “Jerusalem of the West” due to its ever-expanding Jewish population. Before the Nazi invasion in 1940, there were roughly 140,000-150,000 Jews living in The Netherlands, with the largest percentage concentrated in Amsterdam and the Plantage. By the end of the war, only 35,000 had escaped death at Nazi hands.

Hollandsche Schouwburg (Old Dutch Theater and site of the National Holocaust Memorial)

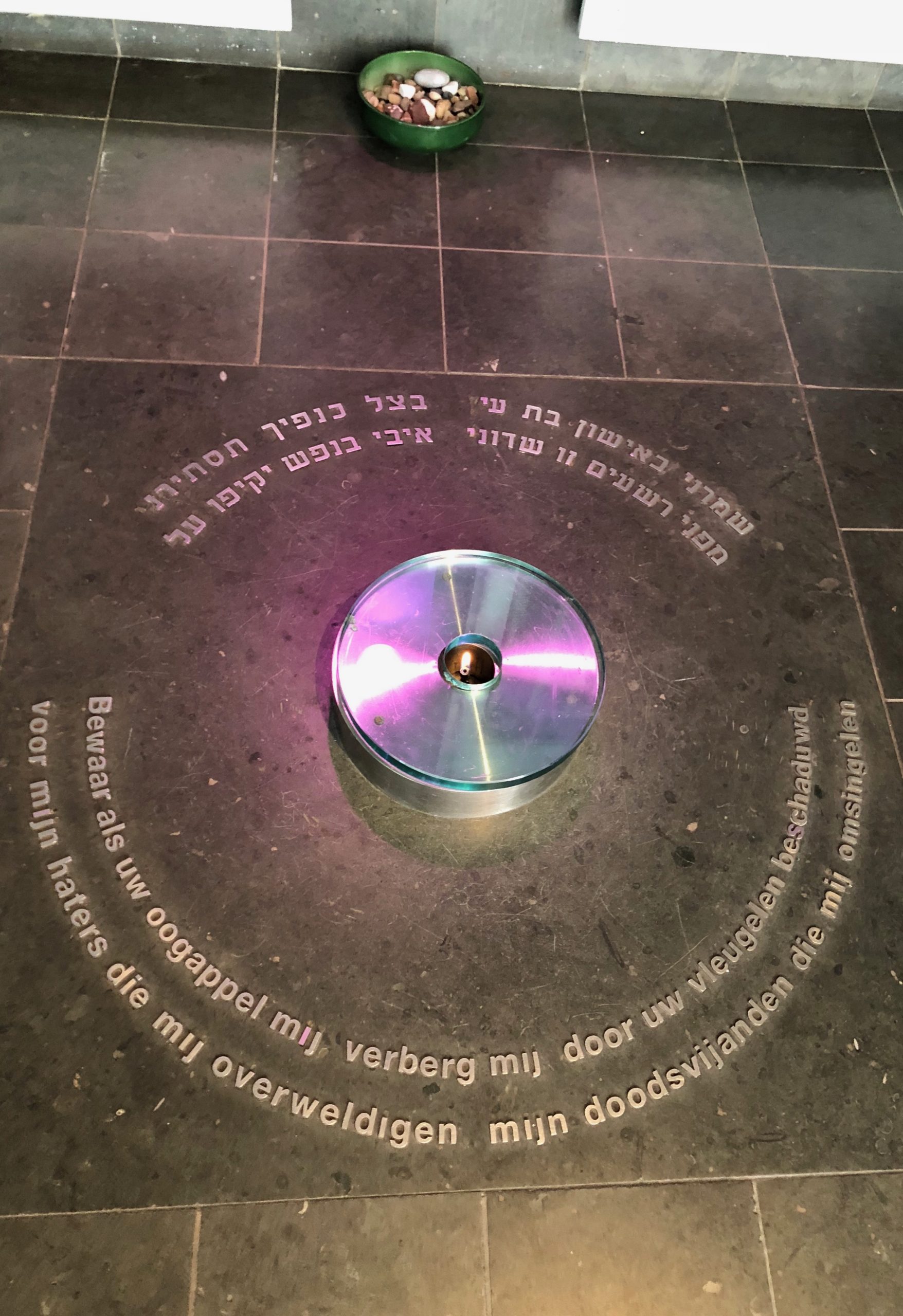

Nearby in the Plantage is the bombed-out shell of the Hollandsche Schouwburg, an old Jewish theater that was commandeered by the Nazis and used as a holding center for Dutch Jews before they were transported to their deaths at concentration camps in the countryside. Tens of thousands of Jews spent time at the theater between 1940-45. A monument has been erected in the former auditorium of the theater and the known names of the victims have been inscribed on the walls of the theater.

Across the street from the theater was a training school for new teachers, which is currently being turned into the National Holocaust Museum. The school remained open during the Nazi Occupation and teachers would risk their lives every night sneaking over to theater and smuggling children back to the school where they would be given over to an Underground Railroad of sorts that transported Jewish children out of the cities and placed them with families on farms where they could be more easily hidden. Not knowing their fates, mothers and fathers would have to give up their children, ultimately never seeing them again. By the time the Nazis were expelled from The Netherlands, over 75% of the Jewish population had been murdered and the Dutch would have to grapple with what had transpired for decades to come.

Portugese Synagoge (Portuguese Synagogue)

Dominating the Plantage skyline is the Portugese Synagoge, or Esnoga. Built in 1675 during the Golden Age, the wealthy Jewish merchant class was able to fund a large enough synagogue to house the exploding Jewish population. The chandeliers are original and have not been converted to contain electric lights. Despite being a tourist attraction in its own right, the synagogue is still a functioning house of worship, and thousands of candles are lit on the chandeliers when required. Next to the synagogue is the oldest Jewish library in continuous use in the world.

During World War II, Nazi occupiers alternated between wanting to turn the synagogue into a deportation center and tearing it down completely. Dutch officials managed to dissuade them from enacting either plan and the building was miraculously spared during the war. The synagogue is easily one of the most peaceful places in all of Amsterdam. I visited in the late afternoon after a long day of scurrying around the city. I plopped down in the one of the pews and suddenly a calm washed all over me. The building appeared to instill a reverence in all the visitors; the only sound to be heard was the dulcet creaking of the floorboards as people soaked up the history seeping from the pores in the walls. The natural light filtered through the lightly-tinted stained glass definitely helped propel the atmosphere to another level.

Verzetsmuseum (Resistance Museum)

Visiting the Verzetsmuseum is a profound and moving experience that brings to light what life was like in Nazi-occupied Netherlands/Amsterdam. The Nazi army invaded The Netherlands in the spring of 1940 and the Dutch were defeated in a mere four days. The country was occupied for five years, during which time both Jews and non-Jews alike resisted their German occupiers.

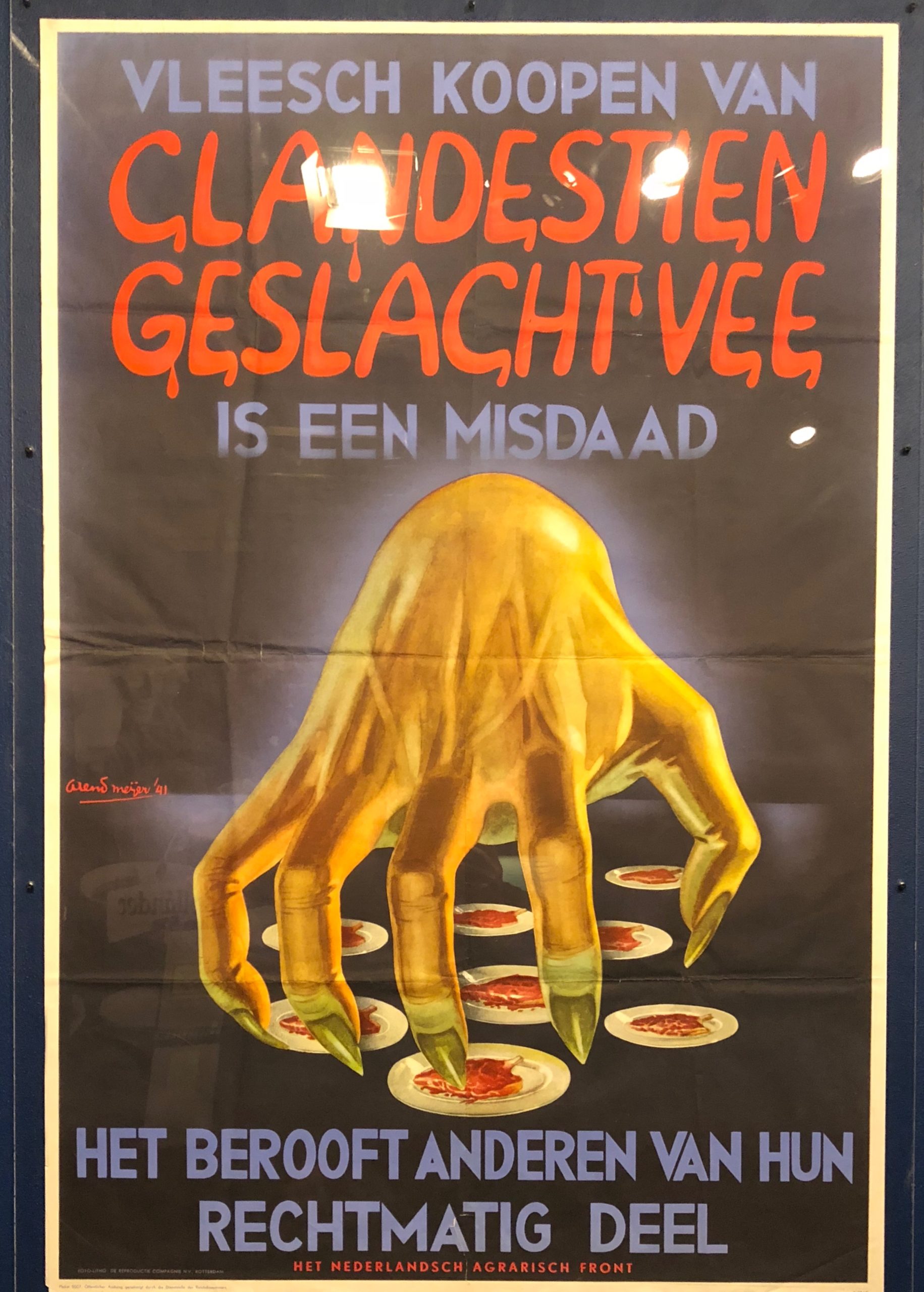

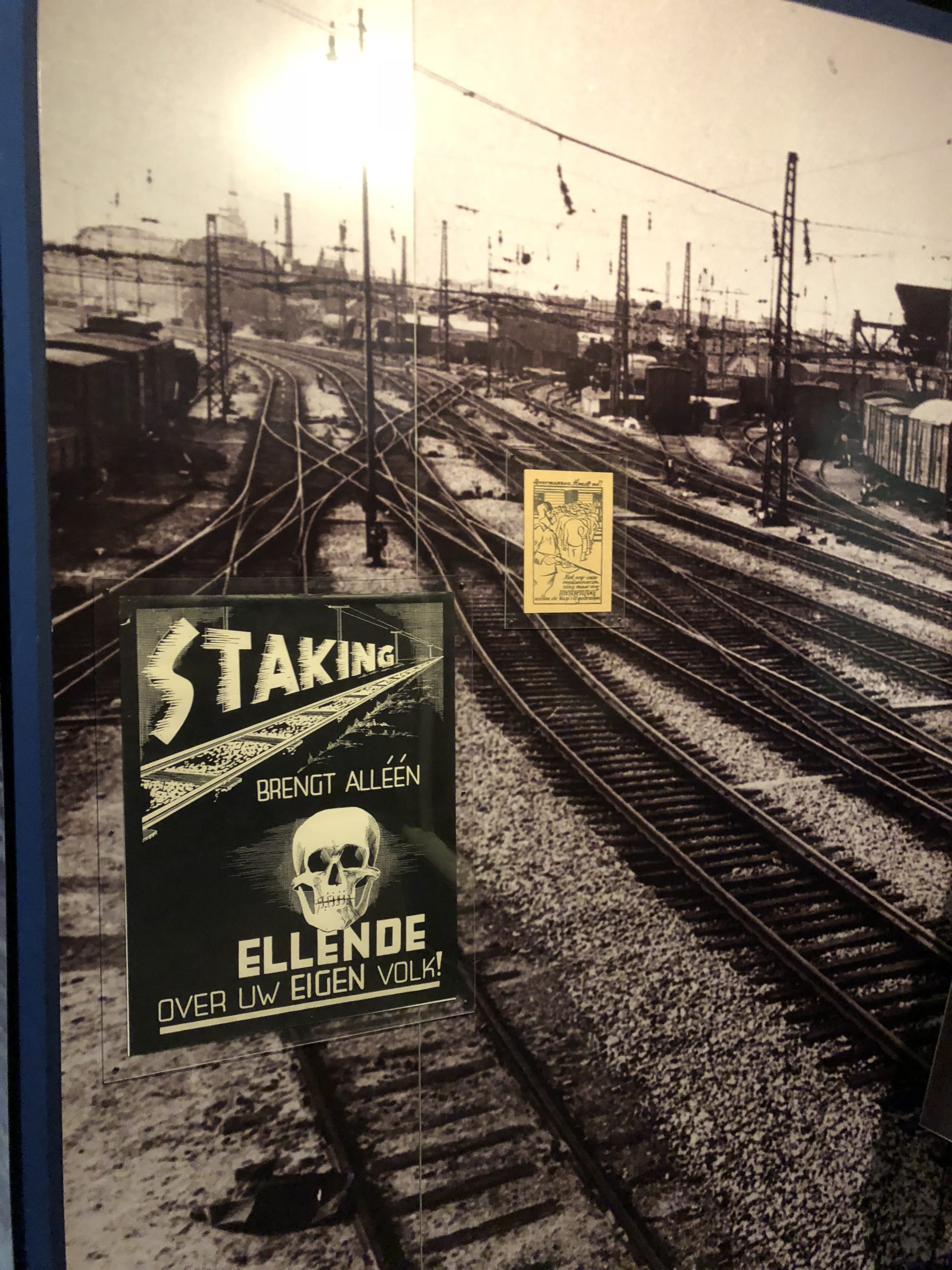

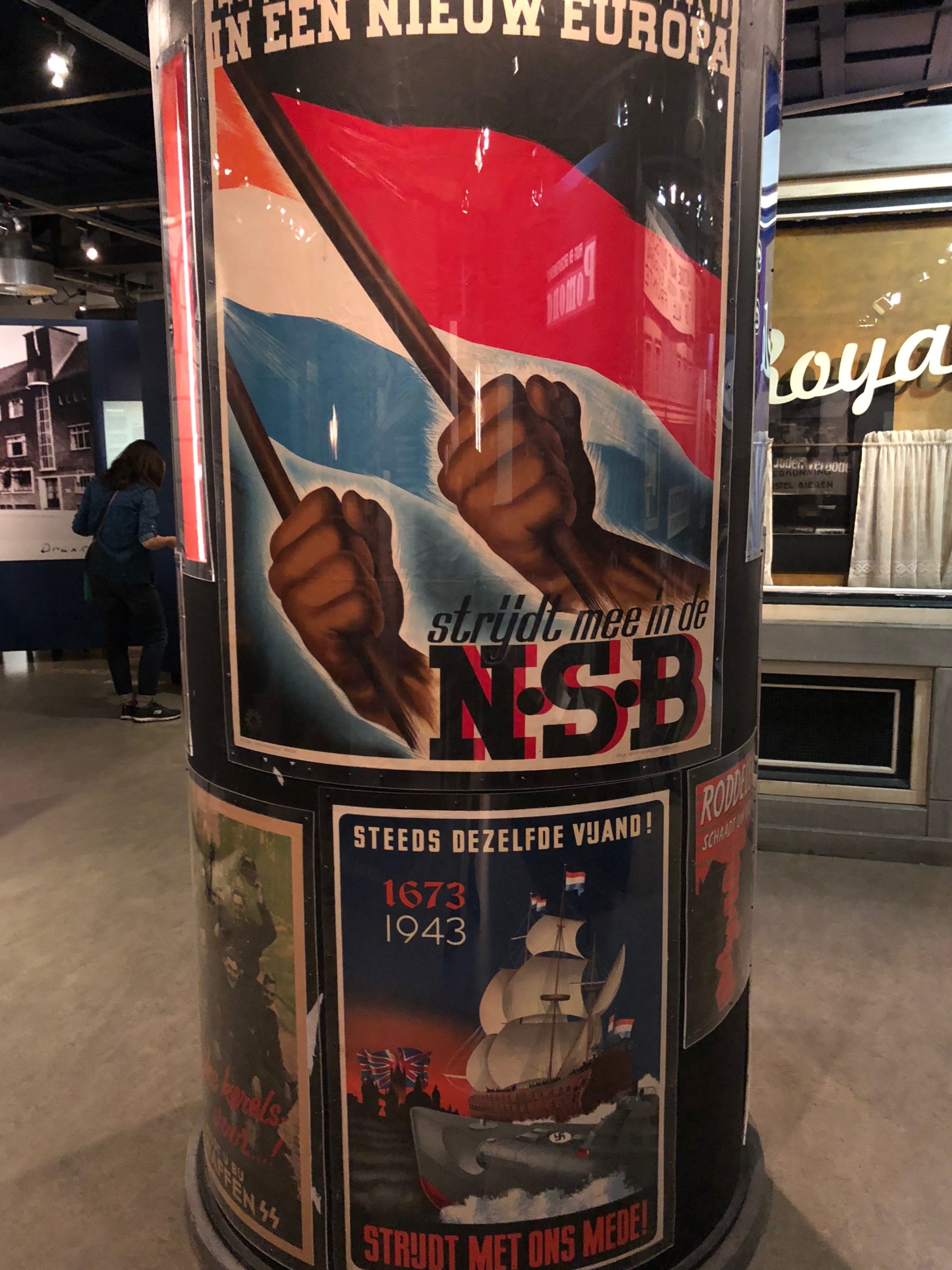

The Nazis never wavered from their “Final Solution” plans of exterminating all Jews, homosexuals and Romani, but they played their endgame for the non-Jewish Dutch closer to the vest. At first, non-Jews were allowed to go about their daily lives with relatively few changes. German propaganda flooded the newspaper and airwaves, but schools, businesses and the like remained open. The goal was to indoctrinate all non-Jews and bring them into the Third Reich’s fold. As soon as the non-Jews caught on to what was happening to their Jewish and homosexual neighbors, transit and agricultural strikes arose all over the country. The Nazis retaliated with brutal force. By 1942, it was clear that the Dutch would not be so easily tamed and turned. Violent methods were employed to drive resistance movements underground.

Unlike the dry audio guide at the Koninklijk Paleis, the audio guide at the Verzetsmuseum is excellent. The museum itself is set up in thematic little rooms that make you feel like you’re walking down a street circa 1940 and peering into the home lives of various inhabitants. The audio guide includes excerpts from diaries and personal accounts from survivors of the occupation. The museum only recently opened in 1999; the exhibits are interactive, contain multi-media and are far from the dusty displays you may find at other history museums.

While the other museums in the Jewish Quarter explain the Holocaust from the victims’ point of view, the Verzetsmuseum examines both how non-Jewish citizens stood up against the Nazis on behalf of the Jewish community, and also how others turned a blind eye in order to survive (and how those in the latter camp had to reconcile their actions after the war). Note that the Verzetsmuseum is not included in the one month Jewish Cultural Quarter ticket; tickets can be purchased separately at the museum box office.

Anne Frank Huis

Although not in the Plantage district, I would be remiss to talk about Jewish history in Amsterdam without mentioning the Anne Frank Huis, one of Amsterdam’s most popular and difficult to visit attractions. I previously visited Amsterdam as a teenager and was able to see the attic were Anne, her sister, mother and father, as well as four other people, were hidden from the world for two years before being discovered by the Gestapo and sent to concentration camps. Anne kept a detailed diary during her time in the attic and remained optimistic about humanity despite the tragic circumstances around her. Anne and everyone else from the attic, save for her father, Otto Frank, perished in the camps. After the war, Otto returned to Amsterdam and found Anne’s diary. He published the book in 1947; it has since been translated into 70 languages as well as dramatized for the stage and screen.

During my visit in 2001, it was easy to walk right up to the museum, purchase a ticket and go in. Nearly 20 years later, things have changed. The demand has become so great, that tickets go on sale two months in advance for each visiting date (e.g. tickets for May 5th go on sale March 5th; tickets for November 23rd go on sale September 23rd). A small number of tickets are withheld for a virtual lottery that begins each morning, but I found this impossible to win. There is no easy way to visit the museum, and certainly don’t count on making a spur-of-the-moment trip to Amsterdam and gaining access.

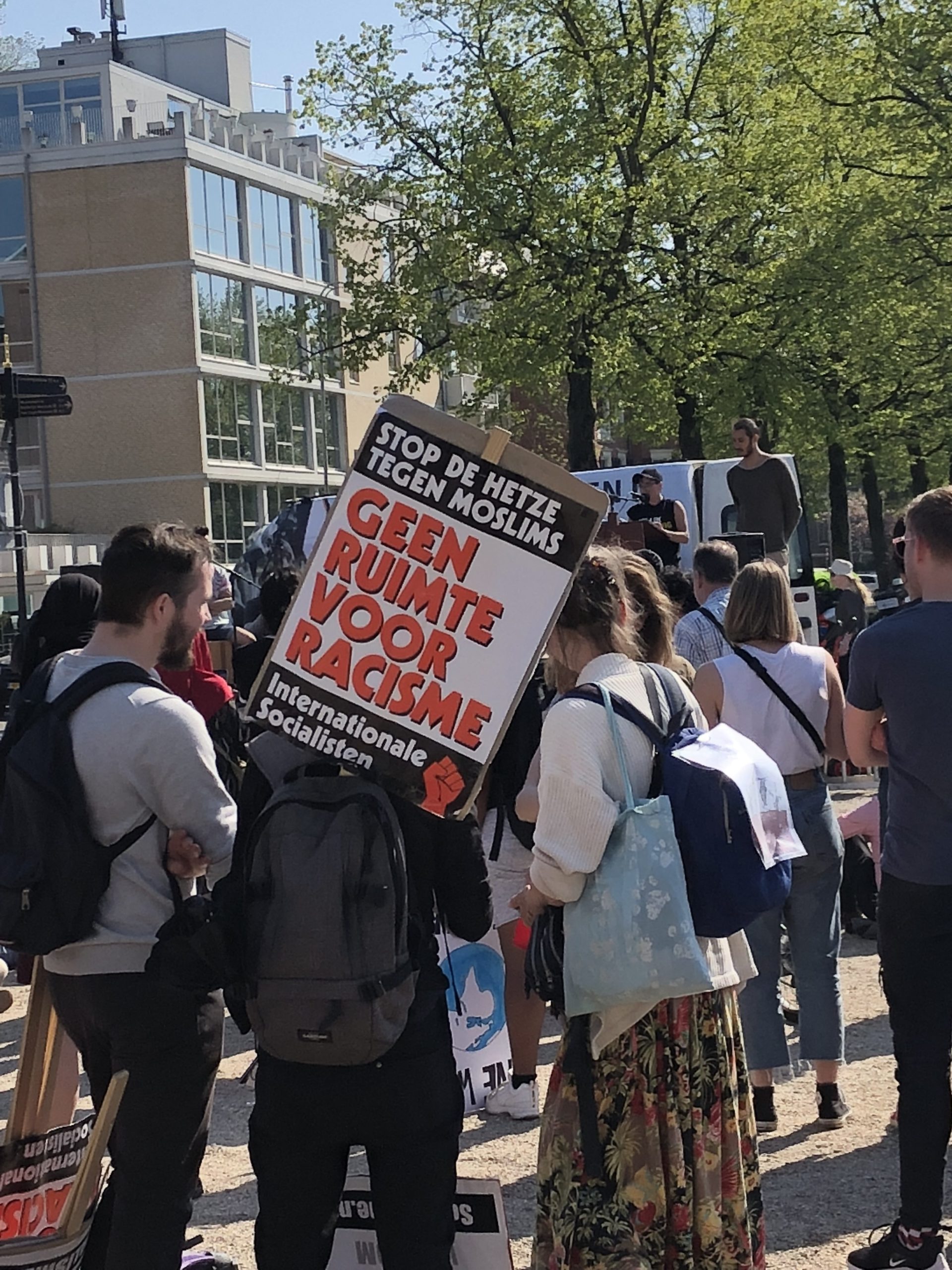

Political Activism Carries On

“Hippies” may not exist anymore, but the legacy of the Dutch Counter Culture is still making history today. I stumbled upon a mini-Woodstock, with protestors demanding better protections for immigrants and refugees in The Netherlands. Songs, slam poetry and fiery speeches were the order of the day. Several spectators were happy to translate and fill me in on the proceedings and I enjoyed witnessing the Dutch rebellious spirit in action.

My travels in Amsterdam were a nice reminder that history is not just the past, but the present too. History is a living, breathing organism moving through society. It isn’t contained in textbooks and museums. It oozes out into the streets and affects all aspects of life. The Dutch are who they are because their history has molded them that way. Still, they don’t allow the clay to harden and set; the Dutch are constantly reshaping and reimagining themselves into a better future. They are clear-eyed about their past, and more than I’ve seen in some other places, they are willing admit their mistakes and learn from them.