Sometimes when you travel, you experience a massive stroke of luck that can only be explained by the travel gods smiling down on you. You happen to be in the perfect place at the exact moment to meet the right person or step into that certain subway car and presto, the course of your trip has changed forever. One such event transpired in Benin’s capital when I decided to visit the Musée Ethnographique de Porto-Novo (Porto-Novo Ethnographic Museum) on my second day in the city.

As is so often the case in West Africa, I was offered an English-speaking guide upon paying my admission to the museum. I immediately hit it off with Rodrigue, a former school teacher, who had left the profession to work at the museum and find tourists to potentially show around Porto-Novo and beyond. Rodrigue was born, grew up, got married and is currently raising his four children in Porto-Novo. Suffice it to say, he has an inexhaustible knowledge of all things Porto, as well as an encyclopedic appreciation of the historical and cultural facets of Benin. At the conclusion of the Ethnographic Museum tour, Rodrigue asked if I would like for him to show me around the following day. We worked out a daily rate and he promised to tailor all activities to my interests; with this simple introduction, the course of my time in Porto would become forever altered- and for the better!

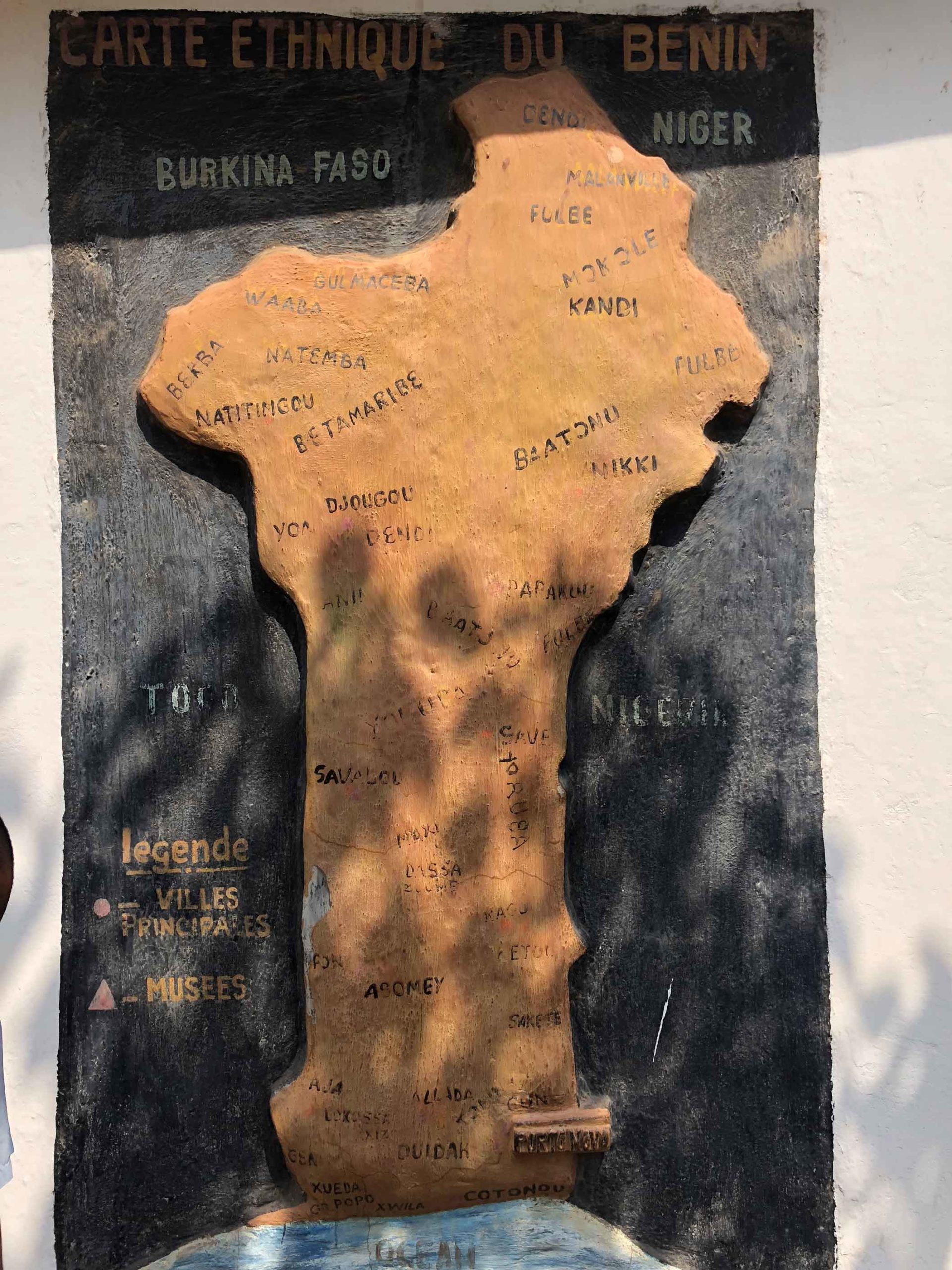

Musée Ethnographique de Porto-Novo (Porto-Novo Ethnographic Museum)

Porto is a museum lover’s paradise. If you want to learn about the history and culture of Benin, especially the Vodun (Voodoo) traditions that originated here and in neighboring Togo, then you could easily spend several days in the capital without getting bored, and the Porto Ethnographic Museum is a perfect place to begin your museum hopping. This humble institution acts as an introduction to all things Béninois, and if Rodrigue is any indiction of the quality of guide at this establishment, then you are sure to get your cultural exploration off on the right foot.

The museum, which was founded in 1957, is housed in a French colonial building that has been beautifully maintained and restored over the years. On display inside are an assortment of traditional costumes, instruments and models of rural dwellings from all over Benin. French is one of the official languages of the small nation, but there are an estimated 50 indigenous languages spoken within the country’s borders. Fon and Yoruba are the two most common, but you can hear a half dozen more spoken in the capital alone.

Before the Portuguese first docked their ships on Béninois soil in the late-15th Century, the area east of present-day Togo was known as the Kingdom of Dahomey, ruled by the Fon people who stationed their capital in Abomey; the Royal Palaces of Abomey are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. To the east, in present-day Nigeria, the Oyo Kingdom, comprised of the Yoruba people, spilled into Benin’s territory and encompassed the city-state of Porto-Novo.

Instead of engaging in battle with the powerful kings of Dahomey, the Portuguese worked with them, encouraging the rulers to expand their territory and sell any prisoners of war to the Portuguese. These prisoners were then carted off to Ouidah or Porto before being shipped across the Atlantic in the slave trade. At the height of this arrangement, the Dahomey kings were receiving the equivalent of 250,000 British pounds each year for the men, women and children they provided to the colonial powers. This makes for a difficult past for the Béninois to reconcile with, and in 1999 the President of Benin made a public apology for the role the local people played in perpetuating the slave trade. In the 1780s, 10,200 slaves were shipped out of Dahomey each year. Even though slavery was abolished throughout Europe by the early 19th Century, the last slave ship didn’t depart Dahomey until 1885, when Brazil finally put an end to the practice of buying slaves.

Without the influx of cash from the various colonial powers who had built forts along the Dahomey coast, the Fon Kingdom began to weaken. The French slowly began acquiring bits of land throughout Dahomey and Oyo, until in 1899 the new colony of French Dahomey was born. The French ruled Dahomey until August 1, 1960, when Dahomey was granted independence and recognized by the United Nations as a sovereign state. The struggle for independence was led by Hubert Maga, who eventually was elected the first President of Dahomey.

Three large factions began to form in the fledging nation and a Presidential Council was created, comprised of an elected president from each group- one being Maga- to rule over Dahomey. Even with the compromise of shared power, considerable levels of unrest remained within the population. In 1972, Lt. Col. Mathieu Kérékou led a coup against the Presidential Council, and by 1974 he assumed total control of Dahomey and declared the nation a Marxist-Leninist State. On November 30, 1975, Kérékou officially changed Dahomey’s name to the People’s Republic of Benin.

Kérékou quickly dissolved all political parties except for his own and in 1979 he held elections where his was the only name on the ballot. He began by nationalizing the oil and banking industries; soon all businesses were seized from their owners and transferred to the state as well. Foreign investments disappeared and the economy went into a tailspin. Teachers at all levels of education quit en masse when Kérékou instituted a policy known as “poverty is not a fatality” in the 1980s. He began buying and disposing of nuclear waste from the Soviet Union to fund the government, but by 1989 the USSR was collapsing and when Kérékou couldn’t pay the army any longer, they rebelled and forced a change at the top.

In 1990, Marxism-Leninism was abolished, outlawed and the People’s Republic was simply renamed The Republic of Benin. Kérékou lost fair elections in 1991 and a multi-party system has existed in Benin ever since. Patrice Talon is the current President, having been elected in 2016. He is of Fon descent and ran on a radical idea that he would push a law through the National Assembly that would limit the Office of the President to a single term. The law failed to pass by three votes, but his progressive actions are to be commended. (Another Talon-initiated advancement is that of the eVisa program for tourist visas- a simple and easy process that allowed me to obtain my visa in a matter of minutes. Other nations in West Africa need to sit up and take note!)

After my in-depth history lesson, I was able to stroll the museum grounds and admire the collection of contemporary Béninois art in the yard. The current exhibition on display featured a series of sculptures made from metal found in trash piles around Porto. The artist then welded the former junk together to form scenes from Béninois history, juxtaposing his traditional heritage with a funky modern medium.

Before leaving the museum, I made plans to meet Rodrigue after breakfast the next day. Rodrigue’s overview of Béninois history was just the tip of the iceberg: my cultural journey through Porto was just getting started.

Temple of Anessan

In the morning, we commenced our adventure at the Temple of Abessan, a sacred Yoruba site made out of red ocher sand that is meant to resemble a termite mound. Abessan is a nine-headed deity who is considered the Queen of the Yoruba people. As the legend goes, three Yoruba warriors were hunting when Abessan and her nine heads appeared to them at this spot. They took this as a sign to set down roots here, and thus the city of Porto-Novo was born.

Palais Royal/Musée Honmé (Royal Palace/Honmé Museum)

Shortlisted by UNESCO as a candidate for inclusion on their World Heritage list, the 19th-Century Royal Palace of King Toffa I has been turned into a museum, granting access to his former residence which contains seven inner atria and a large performance space that is open to the public on holidays and special occasions.

The Musée Honmé follows a pattern of so many museums in the area. If you look online or at signs posted in front of building you will receive the happy news that admission to the museum is completely free. What a deal! Then you attempt to enter the museum and learn that while it is technically free to visit the museum, it is forbidden to enter without a guide. This information is sprung upon you and of course it means you are going to have to tip the guide at the end of the tour.

For the record, I didn’t have any problem being shown around this museum, or any other in West Africa. Most places are short on (English) signage and when you have a guide like I did, who had been working at the Musée Honmé for years and possessed a wealth of knowledge about Toffa and his interactions with the French, it immeasurably enriched the experience. Still, there is that awkward moment at the end where you don’t know how much to give the guide and of course you’ve just gone to the ATM and are stuck with a pocketful of large bills. Always, always have small bills when you go to a museum; the guides will definitely not make change for you. It depends on the length of the tour and the depth of information given, but I found 4000-5000cfa ($7-9US) was generous and appreciated. My only wish was that this fee could have been acknowledged and paid up front. The irony is, the admission to the museum wouldn’t have been a deterrent, but the haggling at the end definitely is.

King Toffa I was born in 1850 and ascended to the throne in 1874, leading the Kingdom of Hogbonou with a progressive edge. He was the first king in Porto to sign a treaty with the French and he helped promote the French language and western curriculum in local schools. Toffa also welcomed Christians and Muslims into Porto without impunity. Because of this, the religious demographics of the capital are roughly one third Vodun followers, one third Christian and one third Muslim. Toffa laid the groundwork for the multi-culture fabric that defines the city today.

There is still a King of the Hogbonou, just as many other ethnic groups retain their kings, queens and royal monarchies. These rulers may carry great sway within their given communities, but in reality, as Rodrigue explained to me, they have little to no actual political capital. Perhaps this isn’t the best comparison, but the current kings and queens feel a bit like the British monarchy. They are figureheads and surely have their devotees, but the average person in Benin does not pay them much mind.

Temple des Zangbetos

Another aspect of the power structure within Benin’s ethnic groups that still survives today is that of the Zangbeto. Above is the Temple des Zangbetos in Porto-Novo, where all rules and decisions regarding this society are made. Zangbeto are known as “Vodun guardians of the night,” essentially acting as a police and security force within the community. They dress up in elaborate costumes that cover their entire head, face and body and patrol the streets aiming to maintain order and break up any trouble. The Zangbeto will dance and entertain for tourists too; I saw one from afar and tried to catch up with him but he turned a corner and disappeared before I could reach him.

Of course, the Zangbeto are not official police officers and can’t arrest you or ask to see your passport like a member of the police or military can do at any time. They are more akin to a neighborhood watch and if you have a problem with someone and don’t want to escalate it into an official criminal matter, the Zangbeto can intervene and act as a peer mediator. They have deep ties with the community and often can arrive at compromises and solutions that a typical court would not. (Interestingly, this is the model of policing that is currently being asked for in America by groups like Black Lives Matter. Rather than employing police that are disconnected and at odds with a community, the police force should come from the neighborhood they are trying to protect, armed with ideas for fixing the problems only they truly can understand.)

Place Toffa (formerly Jardin Place Jean Bayol)

Next, Rodrigue brought me to Place Toffa, Porto’s central square and park, whose centerpiece is this giant statue to King Toffa I. This meeting place was once named after Jean Bayol, a French explorer and administrator who held posts all over French West Africa, from Senegal to Dahomey. As the trans-Atlantic slave trade ceased to operate, Bayol was instrumental in acquiring land for the French during the so-called “Scramble for Africa” that commenced after the Berlin Conference of 1884. Bayol stoked tensions between the Fon leaders in Abomey and the kings of Porto-Novo, eventually surrendering Porto to greater Dahomey and uniting the two regions before declaring the whole of Dahomey as a French colony in 1899. (Bayol died in 1902, having completed his mission for the French government.) The square has since been renamed after a true visionary of what the melting pot of Benin was to become and Bayol has vanished to the footnotes in the tome of world history where he belongs.

Grande Mosquée de Porto-Novo

Аs King Toffa welcomed Christians and Muslims into the city, it’s no surprise that churches and mosques began to pop up in equal measure. The Great Mosque of Porto-Novo looks nothing like a mosque, and that’s by design. Built by Agudás, the name given to freed Brazilian slaves who returned to Dahomey/Benin from the Americas, the mosque was developed in an Afro-Brazilian architectural style that permeates through the oldest sector of the capital. The Great Mosque was built between 1912 and 1925, and everything from the stucco molding to the dual towers is reminiscent of protestant churches built in the Brazilian interior.

The mosque, which is badly in need of restoration, has recently been fast-tracked for consideration by the UNESCO committee and is set to receive funds for its upkeep from the city government. On the side streets radiating out from the Great Mosque is the decidedly low-key grande marché of Porto Novo. What it lacks in hustle and bustle, it makes up for in lower prices and less aggressive haggling than the other grande marchés I encountered in Accra, Lomé and Cotonou.

Cathédrale Notre Dame de l’Immaculée Conception

Not far from the mosque is Notre Dame Cathedral, the largest church in Porto and the center of Catholic life in the capital. The cathedral recently celebrated its 75th anniversary, and unlike the Great Mosque, the building has been kept in tip-top shape. Like most Catholic Churches in West Africa, an adjacent school offers an alternative to the public schooling provided by the state.

Rodrigue and I happened to show up just as the Catholic school children were taking a break for lunch and I found myself immediately swarmed by the curious kids. Mostly they wanted to pose for photos on the cathedral steps, my favorite of which I have shared above. Kids are kids all over the world, and one of the true joys of traveling through West Africa is getting to interact the children and hearing them yell out, “Yovo! Yovo!” (Yovo means white person) everywhere you go. Sally Struthers is so concerned with “saving” the children, but in reality most kids just want to be goofy and have some fun.

Musée Ibugbé Isebayé

The Musée Ibugbé Isebayé is devoted to the history of Vodun culture and also (randomly) features a contemporary art space. Most of the museum is off-limits for photography, but I was able to take a pic of this scene detailing the practice of Fa divination. Fa is a type of Vodun that is practiced by both the Fon and Yoruba peoples. Spirits are believed to inhabit palm nuts that when blessed and prepared correctly, can reveal the wishes of the spirits. The palm nuts are carefully cast by a priest so that they will fall into one of the patterns drawn on the back wall of this exhibit. The priest is then able to translate whatever message the spirits would like to send. All of Vodun is deeply intertwined with the natural world and the spirits of the plants and animals that inhabit it.

Temple Vodun Djihoue

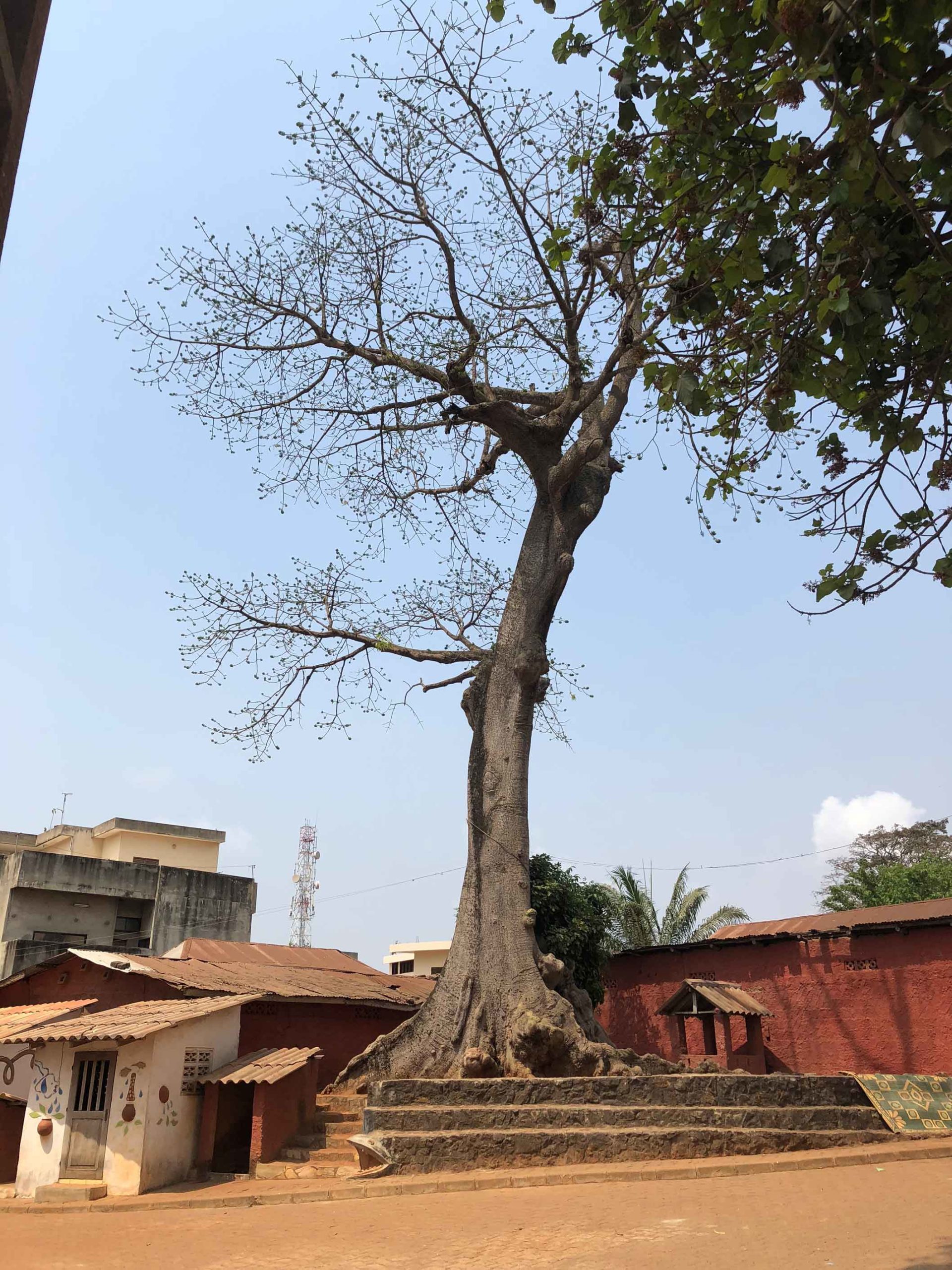

To bring our religious pilgrimage through Porto full circle, Rodrigue took me to a Vodun temple where we were shown around by a local worshipper. I noticed a lot of similarities between Vodun and Catholic/Orthodox Christianity, such as Catholics pray to saints in the same way those who practice Vodun pray to trees, snakes and other fetishes. When Christian missionaries first started to descend on Dahomey, it is easy to understand how elements of Vodun were incorporated into Catholicism and vice versa.

This sacred tree on the temple grounds was just starting to bud again after recovering from a botanical malady, a sign that prosperous times were soon to come for its Vodun community. Next to that tree, in the little white hut to the left, was the snake house, where one could present offerings and craft prayers to the spirit world. (The woman showing us around assured Rodrigue and I that there weren’t any rogue snakes slithering around the temple!)

The temple had also recently installed a set of tiled steps that cascaded down towards the Porto Lagoon where fishermen still earn a living casting their nets from their pirogues. Young Béninois painters and sculptors were given the opportunity to showcase their artwork along this atmospheric walkway and the temple has become something of an outdoor art museum. In fact, the entire neighborhood surrounding the temple has been a breeding ground for so many aspiring artists that the main thoroughfare has been dubbed “La Rue des Artistes” (The Street of Artists).

Monument aux Morts (Monument to the Martyrs)

After we finished up at the temple, Rodrigue was ready show me some more recent history near the National Assembly. Porto-Novo is the one true capital of Benin, being the seat of the President and the National Assembly, but almost all other government departments and foreign embassies are located in Cotonou, which is also the economic center of the nation. Because of this, Porto is often overlooked as a tourist destination, but as you can see, that shouldn’t be the case!

Rodrigue told me I was free to take pictures of the National Assembly, but the guards with guns at the front gate made me leery and I opted not to. Instead I took some photos of the royal-palm-flanked Monument aux Morts to the side of the congressional building, which felt a lot safer. This monument was unveiled in 2010 in celebration of the 50th Anniversary of Béninois independence. Note that the inscription dedicates the monument to all the children of Benin who died for her freedom and not solely for her independence. This includes all those who were arrested and killed during the Marxist dictatorship in addition to those who fell during the fight for independence from the French in the 1950s. Like many African nations, colonialism left high hurdles for the people to overcome, but Benin seems to be solidly on the path of democracy, even if it took a few extra decades to get there.

Zem and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Although Rodrigue and I spent most of the day on foot, we did flag down the occasional zem to zip us across town. In Togo you take a moto-taxi, but in Benin motos are called zémidjans, or zems for short. You can go anywhere in Porto by zem for just a few hundred cfa, but make sure you negotiate and agree on the price before hopping on the back of someone’s bike.

Porto’s street grid was drawn up so that all major intersections in town would be roundabouts rather than four-way traffic stops; there are very few traffic lights in the capital. Instead of planting floral arrangements in the middle of these roundabouts, over the past two decades the city government has turned them into outdoor contemporary sculpture exhibition spaces, granting local artists the chance to flex their muscles and beautify the city in the process. I think my zem driver thought I was crazy when I asked him to keep circling this roundabout until I snapped the perfect photo. (Don’t worry, he got a nice tip for his trouble!) If you’re interested in seeing the sculptures and statues at the various roundabouts, the best thing to do is find a zem driver who is willing to take you to all of them; they will also be aware of street art and monuments that you would never find on your own. Work out a fair price for an hour or two of their time and you’ll be set.

Musée da Silva

The Musée da Silva tells the story of Benin’s history from the 17th Century to the present through the lens of a wealthy family and the documents and artifacts they have collected over the years. The ancestors of the da Silvas had once been sold into slavery and sent to Brazil where they worked until their descendants were eventually freed. After this new generation returned to Porto-Novo as Agudás, who have since formed the foundation of the middle class in Benin, the family prospered and built their home in the Afro-Brazilian style.

The da Silva manor, which was built in 1870, embodies many of the main characteristics of Afro-Brazilian architecture. Airy verandas and enclosed central galleries were important features to deal with the tropical climates in both Brazil and Benin. Living quarters were also often raised off the ground as a protection against flooding in the rainy season. (Seasons are divided between dry and rainy in West Africa, rather than the four-season model we are used to in the United States.)

Admission to the museum provides you with a tour guide and although photos of the exhibitions inside the manor are not allowed, you are free to take pictures in the outer courtyard. Inside, the da Silva collection chronicles the story of the da Silva family tree dating back to the 17th Century, through their capture into slavery and eventual return to Dahomey in the mid-19th Century. It was interesting to compare the warm welcome the Agudás received with that of the once-exiled Siberian prisoners in the Soviet Union, who after Stalin’s death were allowed to return to their respectives SSRs. The Agudás became merchants and traders, amassing wealth and power. Those who survived the gulags returned to find their homes had been seized and little to no work was available. The Soviet returnees became pariahs, ostracized by their fellow citizens. Ex-slaves were not only rehabilitated into Béninois society, but fully embraced and allowed to flourish.

Of special interest to me were the pieces from the period of the Marxist government in the 1970s. The powerful da Silva family was still able to buy fancy foreign cars, radios and television sets, showing that the wealthy can always find ways to skirt the rules while the “regular” folks struggle. The tour ends with a trip to the exhibition hall next to the residence where films are sometimes screened. The hall tells of Benin’s growth post-Marxism and ties the rights gained by the people since the 1990s together with the civil liberty battles fought for Black people around the world by the likes of Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr.

Maison du Patrimoine et du Tourisme (House of Heritage and Tourism)

Taking note of how the Afro-Brazilian architecture piqued my interest, Rodrigue took me to the government office of Heritage and Tourism, where he knew one of the workers and was sure his friend would let us take a look around the historic building. After greeting Rodrigue’s friend, I got an inside look at the house that was once occupied by a wealthy merchant and his family during the 19th and early-20th Centuries. I know independent travelers sometimes chafe at the idea of walking around with a guide, but I would never have been allowed to see this building if I hadn’t been accompanied by Rodrigue. A canned tour sounds like a drag, but spending this day with Rodrigue occurred organically, and even though I was paying him for his time and expertise, it felt more like two friends walking around than being herded around by a cruise ship director.

Still not satiated, Rodrigue and I walked around Porto’s oldest quarter, admiring the faded glory of the Afro-Brazilian houses that line its streets. There was a definite charm and mystique to the homes; at times it almost felt like we were on a period drama movie set, without a modern building in sight. It’s hard to walk by these homes and not fall at least a little bit in love with Porto.

Lake Yewa/Porto-Novo Lagoon

Rodrigue and I ended our day in the late afternoon on a peaceful and meditative note. We strolled down to the lagoon formed by the Yewa River (and sometimes called Lake Yewa) that is the home to Porto’s fishing population. There is a sign proclaiming that there are manatees in the lagoon, but Rodrigue said he had never seen one and doubted the veracity of the claim. We watched the fishermen filling their pirogues with their daily hauls in silence, subdued by the rhythms of the water and the reeds swaying in the breeze.

It was here, in the calm of nature, that I could finally digest the buffet of history, art and culture I had just stuffed myself with; a picture of what life in Benin and Porto was beginning to come into focus. I have heard backpackers in West Africa accuse Porto of being boring compared to Cotonou, but they are simply mistaking the laidback attitude of its citizens with a lack of things to do. Of course, we can lay some of the blame at the feet of Lonely Planet’s worthless two sentence description of Porto too; I certainly wouldn’t have found half of these museums without the help of Rodrigue. Like most of West Africa, you’re going to have to be more self-sufficient in your pursuits than in other parts of the world. Still, if you are tenacious, the rewards will be as rich as the culture that Porto has to offer. It’s a tale as old as David and Goliath: those we underestimate the most, offer the greatest surprise victories in the end.