Elevator going up?

Or down?

Getting Out of Downtown

Two of Tirana’s best attractions, one a first-rate museum and the other a National Park, are located a mere 25km (16mi) east of the Albanian capital. Getting there by public transportation is cheap and easy to boot. Dozens of bus lines converge behind the Palace of Culture in Skanderberg Square. Simply find a bus headed for Linzë- these buses are painted bright blue, so you can’t miss them- and buy a ticket directly from the bus driver for 40 Lekë (or about 35 cents US). Note that having exact change is encouraged and large bills will not be excepted at all.

Now that BUNK’ART’s popularity has grown, most of the Linzë-bound buses have a sign advertising the museum in their front windows, making this whole process fairly fool-proof. Simply tell the driver where you’re going (as if the driver couldn’t already guess) and he or she will let you off right in front of a tunnel that leads to the museum. After soaking up all that history at BUNK’ART, the entrance to Dajti National Park is a brisk ten minutes walk up a hill. (When I think of the day trip I took from Baku around the Abşeron Peninsula, which involved taking one subway line and transfers to six(!) different public bus lines, this day trip was a piece of cake!)

BUNK’ART

The exact location of Enver Hoxha’s personal bunker was unknown to the general public for many years after the fall of communism in 1992. Once disclosed, ideas were bandied about regarding the bunker’s future, but one immediate issue arose: there was no easy access to the bunker’s remote entrance on the side of the mountain. The tunnel you see above was constructed specifically to lead the public to what eventually became BUNK’ART, a hybrid history and art museum located within a concrete bunker. The tunnel provides a rather ominous start to your museum-going adventure. Not only is the walkway cold and damp, but speakers pump communist-era music into the tunnel. Making my way down the dimly-lit path, I felt like I was being shuttled back in time to an uncertain and unnerving era.

On November 29, 1989, a Hoxha-less communist party enforced a country-wide celebration bearing the motto, “45 vjet çlirim” (45 years of liberation), which marked the anniversary of the end of the Nazi occupation of Albania in 1944 and Hoxha’s rise to power shortly thereafter. The irony that the past 45 years of terror had been anything but “liberation” was not lost on the people, and now symbols from the celebration have been unceremoniously dumped anywhere that’s out of sight and out of mind.

The statistics of Hoxha’s bunker are mind-boggling. This was obviously the largest bunker built in Albania, made up of 106 rooms spread out over five underground levels. This is the only bunker to have an assembly hall, where all parliament members were expected to meet in the event of (nuclear) war. The outer concrete shell of the bunker measures 1m (3ft) in width. The bunker is buried beneath 100m (328ft) of soil and the total area of the bunker is 2685 square meters (28,901 square feet).

Construction began in 1972 and lasted for six grueling years before completion. The impetus for building the bunker came after Hoxha sent a delegation to North Korea in 1964. They reported back to their leader that the Korean dictator installed a personal bunker lest there be an attack from the West. Hoxha started working on plans to follow suit. Today, 24 of the rooms have been opened to the public for BUNK’ART’s use, including Hoxha’s personal offices, bedroom and the assembly hall. (If you pick up the phone in Hoxha’s office, you will hear his voice orating to the people in Skanderberg Square. Spooky.)

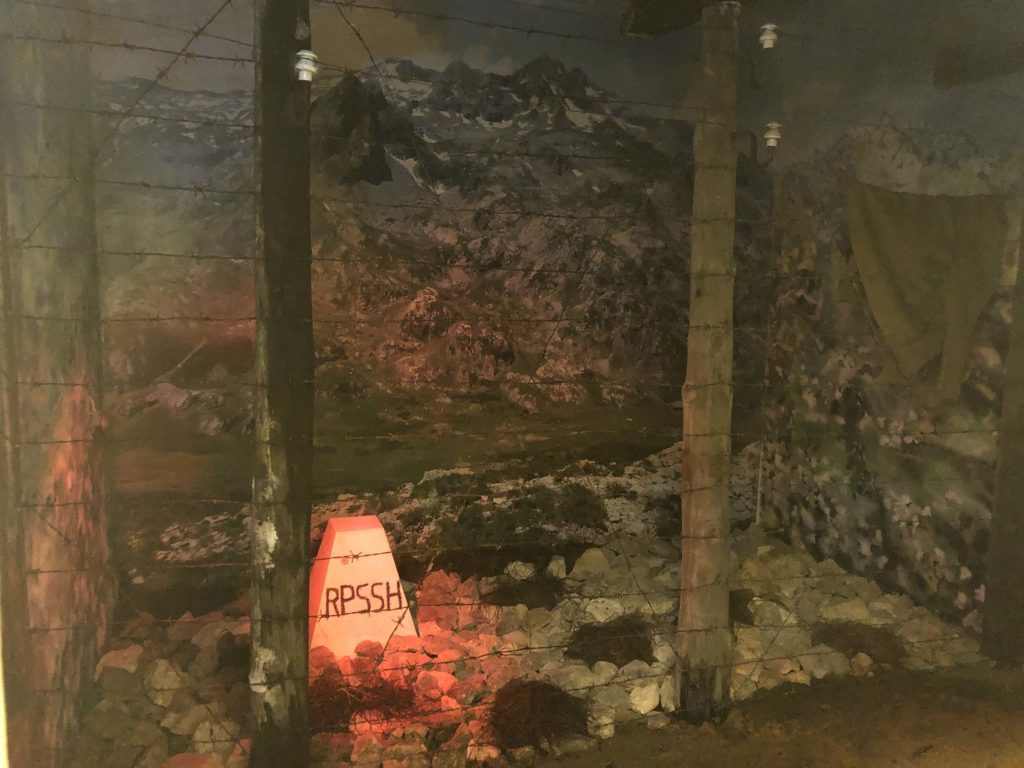

One of the rooms recreates what the Albanian border looked like during Hoxha’s rule. The PPSH (the translated acronym in English) was the only political party allowed to exist in communist Albania. (It’s pretty easy to pass legislation when you only have one political party!) It’s important to note that Hoxha didn’t officially rule by executive order. Going through the motions of the bureaucratic process was very important so that the people were given the illusion that his decrees were actually the will of the elected officials. A motion, such as closings the borders, would be put forth and the merits of which would be “debated” by the parliament. After all the hoops were jumped through, there would be a unanimous vote and the law would be enacted.

One room had a sign instructing me to shut the door and press a button. Upon doing so, the room filled with “smoke” (water vapor) in an attempt to simulate an attack with biological weapons. Instead of fire drills or tornado drills, the likes of which I routinely practiced in grade school, Hoxha had Albanian youngsters learning how to put on gas masks and preparing for all-out war. Fear of the unknown was a vital tool in Hoxha’s arsenal.

During Hoxha’s initiative known as bunkerizimi (bunkerization), around 175,000 bunkers were built across the country. One aspect of the bunkers that does not get discussed very often is that hundreds of engineers and construction workers died while carrying out Hoxha’s fanatical plans. It is self-evident that those who were killed attempting to cross the border or in Hoxha’s forced-labor camps were victims of the communist regime, but these workers- people loyal to Hoxha’s cause- were also victims and should be counted as such.

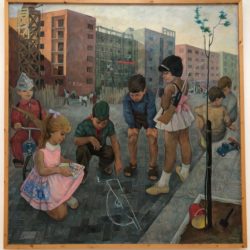

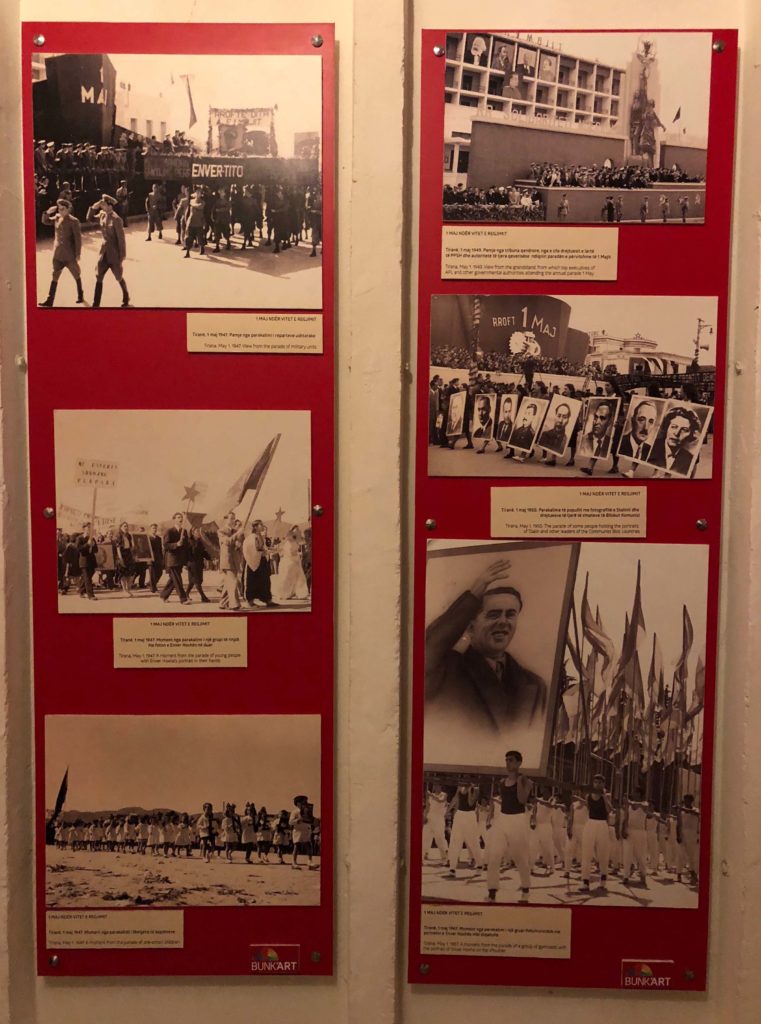

Another interesting room at BUNK’ART discussed the pageantry and parades forced upon the people to remind them how “happy” they were and how much they adored Hoxha. (If you have to be instructed to smile, you’re probably not actually happy!)

You can see in the top left photo that Hoxha and Tito were once allies before things soured between Albania and Yugoslavia in the late 1940s. Young men and women marched through the streets of Tirana carrying enormous paintings of Hoxha and other communists officials as onlookers were expected to cheer from the sidelines. Indoctrination of the youth is a crucial aspect of many totalitarian regimes.

Attendance at Hoxha’s funeral was not optional. Of course, you were not only expected to show up, but to put on a good show as well; extra points were given for weeping and wailing as evidenced above. Naturally, like other totalitarian regimes, there were people who bought into the party line and genuinely supported Hoxha and the PPSH. It’s easy to turn a blind eye to injustice when you yourself are not being similarly oppressed.

The assembly hall shown above is now used by school groups when they visit the museum; those lucky enough to survive persecution during Hoxha’s rule occasionally give talks here as well, detailing what daily life was like in those times.

Despite Hoxha’s great fears, Albania was never invaded by a foreign power during his Presidency. There was neither a biological attack nor a nuclear one. The countless amounts of time and money spent on building these bunkers was a complete waste and placed an incredible strain on the country’s economy, which was already in the crapper.

Dajti Ekspres

After such a heavy experience in the bunker, my spirits were soon to be lifted (and quite literally) as I rose 1050m (3444ft) up the side of Mt. Dajti in the Dajti Ekspres Cable Car. Founded in 1966, Dajti National Park has provided an escape to nature for the citizens of Tirana for over fifty years.

The cable car ride lasts about twenty minutes and runs everyday except Tuesdays, when it is closed for routine maintenance. Unfortunately, the windows are fairly scratched up, marring what would otherwise be perfect photos, but the views of Tirana and the farms at the mountain’s base are still breathtaking. Plus, who doesn’t love a cable car?

The cable car takes you to a small plateau about 2/3 up the side of Mt. Dajti. There you’ll find a few restaurants, a luxury hotel, horseback riding and a shooting range where you can fire old communist-era weapons at rusty tin cans. If you want to reach the 1613m (5292ft) summit, you’ll have to go the rest of the way on foot. The paths in the National Park are marked with intermittent sign posts, but instead of denoting distance, they list destinations by time, which is not very helpful as everyone hikes at their own pace.

The forest provides plenty of shade and appears peaceful, but this only masks the difficulty of the climb. The trail follows a steep incline up the mountain and I’m embarrassed to say how out of breath I became along the way. I also gulped down my supply of water far too quickly. Some Austrian hikers passing me on their way down took pity and gave me one of their water bottles as they witnessed me panting against the side of a tree.

There are a few hidden historical gems in Dajti as well, including this abandoned hotel, once used by the higher-ups in the communist party. Today it sits derelict and covered with graffiti, long boarded-up after the PPSH lost power.

As much as I struggled to reach the peak, I persevered and eventually got to the top. I have to say, the payoff was worth the effort. There’s a reason why Mt. Dajti is nicknamed the “Balcony of Tirana” and the proof is in the photos. You can see for miles around in every direction and even on a hazy day, you can truly appreciate the breadth of Tirana’s urban sprawl.

Mt. Dajti is only one of several mountains in the park and you could spend some serious time hiking if so desired. There is an active military base on one of the peaks, so steer clear of that, but otherwise there are lakes, caves and ruins in the park all free to explore.

I know some people at my hostel offered the suggestion to do this day trip in reverse: Mt. Dajti in the morning and BUNK’ART in the afternoon. Their reasoning was to go up the mountain early and hike to the top before the cruel Albanian summer sun gets the best of you. Afterwards you can cool off post-lunch in the underground bunker.

This all makes sense, but I still chose to visit BUNK’ART in the morning for two reasons. First, the emotional weight of the museum is pretty intense. By experiencing that first-thing, I had the ability to process what I had learned through some hardcore physical activity, even if the heat did take its toll. (Had I remembered to pack enough water, I would have been fine.) Second, even hiking in the cool of the morning would still wear you out. There’s a lot to read at the museum and your mind needs to be sharp and focused. I could envision my eyes glazing over and just wanting to take a nap rather than make my way through 24 rooms of dense information.

Looking back at this photo it’s hard to believe that I was in a bunker 300 feet below this mountain in the morning and by mid-afternoon I had scaled my way to the very tip top. Travel should be about pushing yourself, both mentally and physically. Do the things you didn’t think you could do and then go one step further. Mt. Dajti put up a good fight, but it didn’t knock me out. I can look up at that peak and know I didn’t give up. Maybe it was reading about the strength of the Albanian people in BUNK’ART that gave me the extra little push I needed to reach the summit. I remained determined and didn’t lose my sense of humor along the way- I even had a good laugh with the Austrians at my expense! I wholeheartedly recommend this day trip if you visit Tirana; it encapsulates so many of the wonderful things this city has to offer and will test your mettle, making you a stronger and better person by day’s end.