Buildings dipped in Cotton Candy

Perhaps I hit my head on that bumpy Balkan bus ride between Podgorica and Tirana, for as soon as my feet touched Albanian soil I looked around and half-expected to hear Jacques Demy yell, “Action!” (This would be doubly frightening as Mr. Demy has been dead for almost thirty years, but I digress.) Surely I had stepped onto the set of Les parapluies de Cherbourg or Les demoiselles de Rochefort; all that was missing was a singing Catherine Deneuve! Alas, I was not in a French musical, but Edi Rama’s post-makeover-montage Albanian capital city. So what was going on with all the brightly-painted buildings done up in a Candyland color palette?

Edi Rama, current Prime Minister and former Mayor of Tirana from 2000-2011, gave the capital city a dramatic facelift during his first term in office. Not only did he redesign Skanderberg Square, but he ordered all the socialist brutalist buildings to be painted over in pinks, yellows, greens and blues. These dour symbols of concrete oppression under dictator-for-life Enver Hoxha now cause you to crack a smile and snap a photo.

The not-very-mighty Lana River cuts through central Tirana and Rama was also responsible for planting thousands of trees along its banks. He added footpaths and benches where one can rest and take in the view. What was once a city of terror is quickly becoming one of Europe’s quirkiest capitals. I definitely felt like an uber-tourist as I paused every ten feet to take another picture of a random apartment building; the city has literally become an attraction in and of itself. This takes the idea of street art to whole new level. And speaking of…

Street Art in Tirana

Competing with the yellow and salmon-colored buildings pictured above, there’s still room for some more traditional street art to pop up on an alley-facing wall. Street art, often rebellious and political in nature, was forbidden under Hoxha’s reign. Self-expression as a concept didn’t exist; the only thoughts you were supposed to think were those that the government put in your head. Now Pandora’s box has been opened and a new wave of Albanian artists have been set free to go wild, using the city as a canvas.

Above you can see the many different faces that make up Tirana. What it means to be Albanian is no longer defined as the happy, smiling communist worker that populated socialist realism paintings. After Albanians overthrew the communist party, the idea of individuality re-entered society. The populace no longer had to identity as a monolith; religious institutions re-opened, opposing political views could be openly expressed and the younger generation began to find their place as Albanians living in a global, interconnected world.

As time marches on, Albanians have made a concerted effort to move on from their past. Just as the last likeness of Enver Hoxha was literally being toppled over in Skanderberg Square, the rest of the Balkans were on the brink of war. Yugoslavia had fractured and Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Croatia were soon to be locked in a bloody battle; Kosovo (historically ethnically Albanian) was about to ignite like a powder keg, detonating a perilous political rift between Serbia and Albania.

Both the Serbs and Albanians accused the other side of committing genocide in Kosovo and it took NATO bombing Belgrade to end the armed conflict now known as The Yugoslav Wars. In 2014, Edi Rama became the first Albanian Prime Minister to visit Serbia in over 70 years. He has since strengthened the relationship between the two countries even further and has equated their partnership to France and Germany repairing their relationship after World War II. As hope springs eternal across Serbia, Kosovo and Albania, the monster painted above has morphed into the symbols of peace as painted by Eldi Veizaj below:

Galeria Kombëtare e Arteve (National Gallery of Arts)/Flaka Haliti

Now that I’ve brought up Kosovo, it’s a good time to transition to the National Gallery of Arts, Albania’s largest art museum. The institution, whose permanent collection contains the greatest assemblage of Albanian socialist realism art in the world, was established in 1946 and has occupied its brutalist home just south of Skanderberg Square since 1974. Due to Hoxha’s extreme isolationist policies, very little Albanian art was exhibited outside of the Motherland and even fewer international artists held showings in Tirana.

All of this has changed with the fall of communism in 1992. While three quarters of the museum are still devoted to displaying socialist realism paintings and sculptures, the rest of the space has been given over to hosting rotating international artists and their works.

I struck gold by getting to experience Kosovar artist Flaka Haliti’s “Here- Or Rather There, Is Over There” when I visited. Born in Prishtina in 1982, this was Haliti’s first solo show in Albania. As the title suggests, Haliti is seeking to destabilize the limiting dichotomies between territories, especially between the East and West. Throughout the exhibit, she breaks down both the physical and mental boundaries we erect that limit us from interacting with other people and cultures.

Clouds play an important role in Haliti’s work. From the ground, clouds appear to be opaque and impossible to penetrate, but of course we know they are merely a collection of water and ice crystals that one can easily pierce. Haliti often photographs clouds and then imposes silly shapes or smiley faces on top of them.

Haliti likes to play tricks with our eyes. Above you see what appear to be concrete road blocks, much like the ones set up all around Prishtina by UN and NATO peacekeeping forces during the war between Serbia and Kosovo. After the war was over, the barricades remained. Artists and children alike have covered them with drawings and symbols of hope, but nevertheless they have not been removed.

In her exhibition, Haliti offers commentary by taking a fresh approach to artistically interacting with the road blocks. Here she created a concrete optical illusion using lightweight strips of wood and plaster. The barriers that we once thought immovable are actually not that heavy and do not need to be seen as the burden we once assumed they were. Like great art, these images are specific to the artist and Prishtina, but can also be universally appreciated and applied to our own lives; citizens of Tirana can certainly relate to the road blocks in their lives with regards to Hoxha’s regime, but hopefully, like Haliti’s faux concrete, Hoxha’s legacy has been easier to dismantle than previously thought.

Galeria Kombëtare e Arteve (National Gallery of Arts)/Permanent Collection

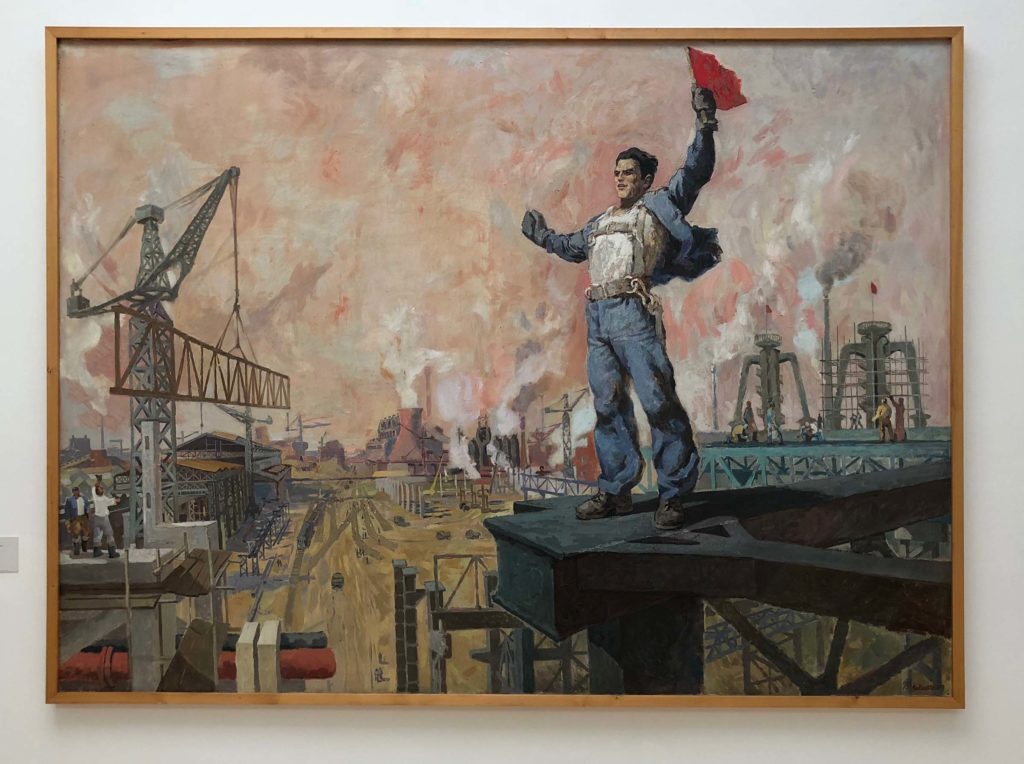

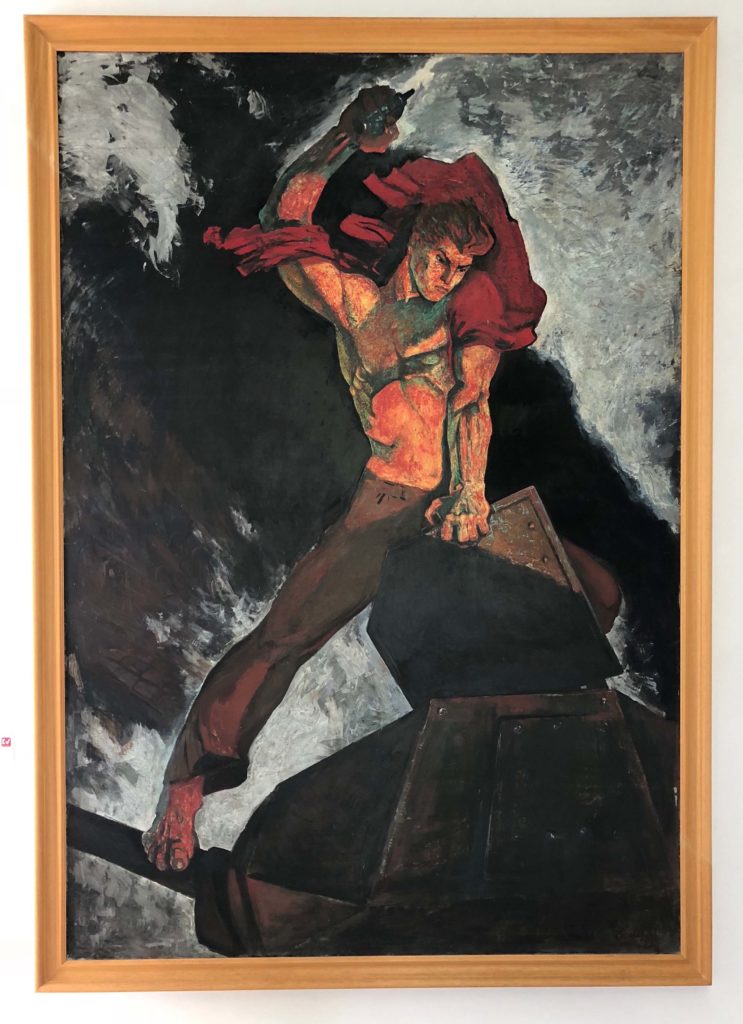

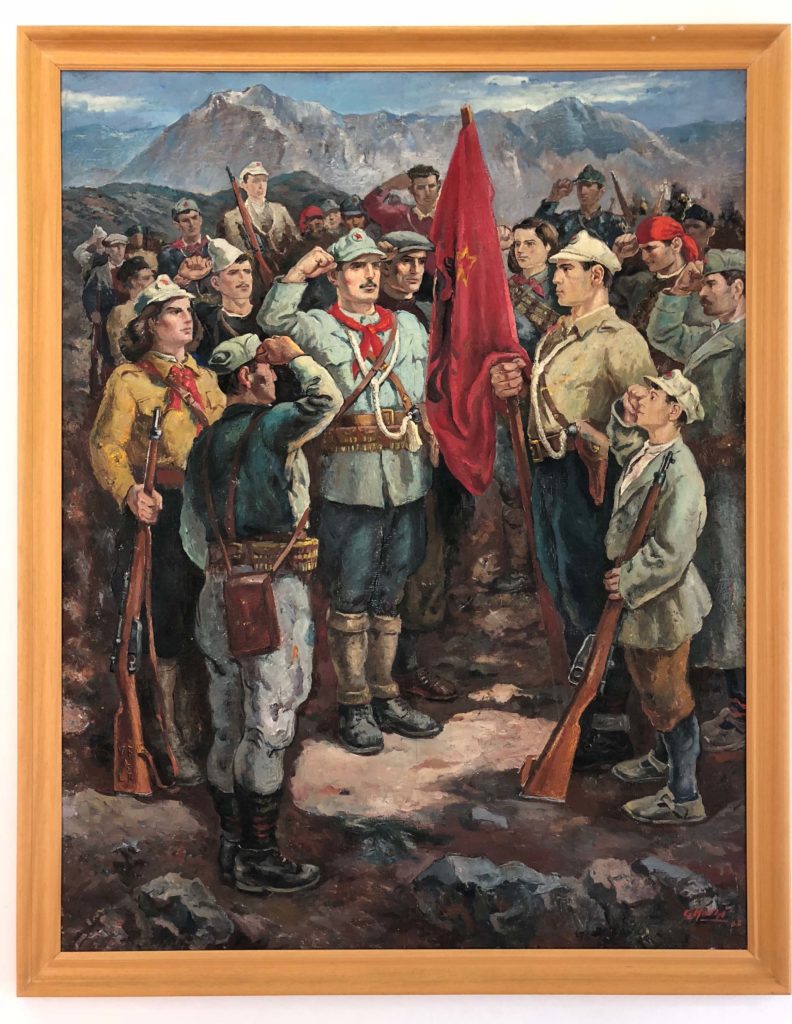

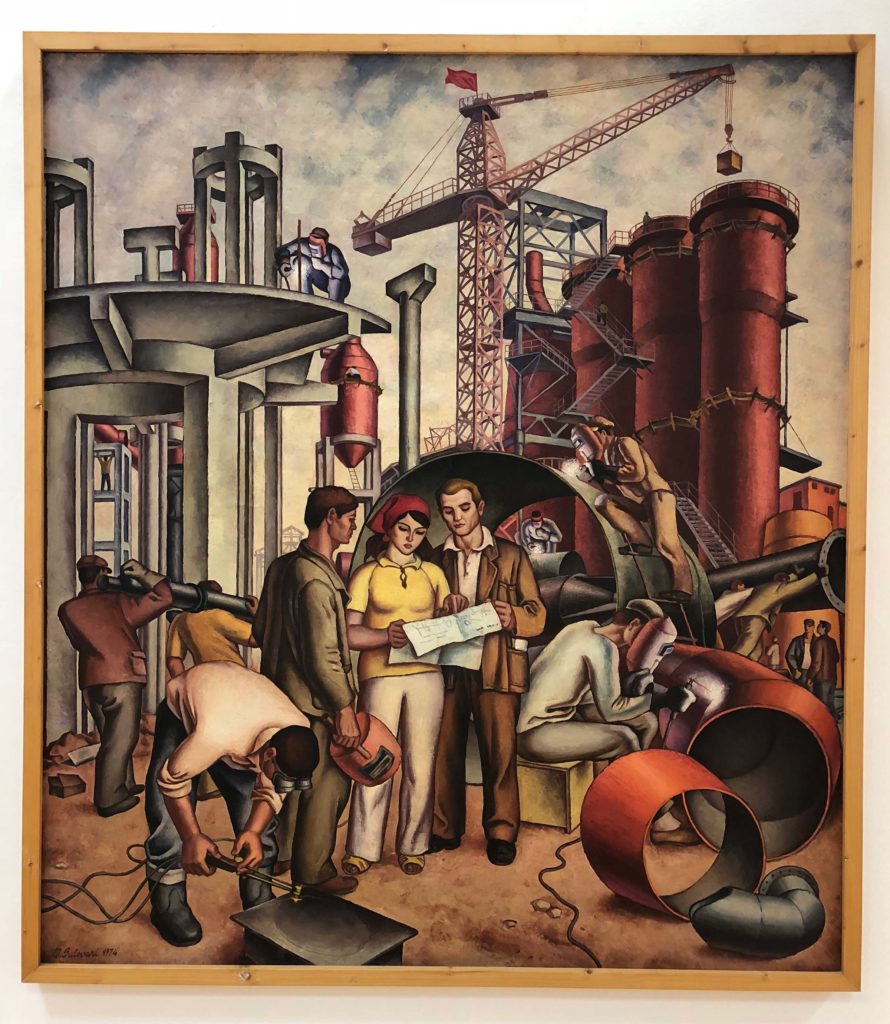

Nowhere else in Tirana are Hoxha’s communist ideals on more prominent display than at the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Arts. Paintings and sculptures from the 1950-80s were such thinly-veiled propaganda pieces that one has to wonder if the veil even existed at all.

This genre of art had several functions. First, it instructed Albanians on the correct way to live. One was supposed to work hard and give tirelessly of oneself for his or her country. The needs of the state were greater than the needs of individual. Toiling in the field or sweating at the steel mill were worthy ways to spend your day; above all else, the worker was glorified and exalted.

The second function was to normalize the new rules of Hoxha’s government. After World War II, private property and business ceased to exist. The government owned all land and in theory would distribute any profits made to all the people equally. In the painting above, you can see the farmers happily turning over their land to a government official. The paintings instructed people that they were supposed to be happy doing this, and life was expected to imitate art.

If there’s anything good to say about Hoxha, it’s that he raised the status of women in Albanian society and tried to make them equal to men. Women were not only valued laborers, but they were put in charge of large-scale projects and given high-ranking government positions. Socialist realism put women front and center in the work force too. Above a female manages the levers at a factory; below a woman is not only at a construction site, but is the one explaining the blueprints to her male co-workers.

Another goal of socialist realism was to extol the (alleged) power and might of the nation. Contrary to the reality that most Albanians were living in total poverty, the images you see depict an advanced country, full of industry and technological wonders. “Sure, we may have it a little rough here, but compared to the rest of the world, we are number one. No one is happier on earth than the Albanian worker!” Hoxha desperately wanted the citizens to feel like they were living in an ultra modern society, and it was all thanks to him, naturally. Who was there to say otherwise?

Reja- The Cloud Pavillon

I couldn’t show you a photo of the exterior of the museum yet because I didn’t want to ruin my final surprise of what awaits for you on the front lawn. Reja- The Cloud has become one of Tirana’s most beloved attractions since being transplanted in front of the National Gallery of Arts from London’s Hyde Park in 2016.

Designed by Japanese artist Sou Fujimoto, The Cloud is composed of white steel rods and plexiglass floor coverings. You are welcome (and encouraged!) to climb through The Cloud as if it were a heavenly jungle gym in which you can walk on air. In the evenings, concerts are given on the lawn with the singers and musicians hovering in The Cloud with their instruments.

Now, I could have written this post chronological, starting with the socialist realism paintings in the museum, followed by The Cloud and Haliti’s special exhibition and concluding with the street art and Edi Rama’s scheme to (literally) paint the town red. But that’s not how I discovered Tirana and it would be a misrepresentation of the city’s character to lead with its past.

Other than “The Albanians” mural above the entry of the National History Museum, the socialist realism artwork has been packed away and can only be seen inside a museum. The communist statues have all been removed and are living out the rest of their lives in a sculpture graveyard behind the National Gallery of Arts. The past is certainly not forgotten, but it isn’t dwelled on either. Hoxha’s horrors have not made the population bitter.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite. The warmth of spirit is strong in Tirana. I was welcomed with open arms everywhere I went. Albanians don’t wear their past on their sleeves, to co-opt a phrase, but rather their bright future leads the way, shining it’s light all over Tirana.