I’m willing to bet that if I handed out surveys to one thousand random people in Times Square, asking them to name five European cities with hot art scenes, Rīga would show up very infrequently, if at all. That’s a shame because the Latvian capital has a lot to offer those with a hunger for art; new galleries and museums are seemingly popping up overnight.

Latvijas Nacionālais mākslas muzejs (Latvian National Museum of Art)

Built in 1905, the home of the National Museum of Art was the first building in the Baltic States constructed expressly for use as a museum. It now houses the largest collection of Latvian art in the world. Recently restored and refurbished in 2015, the grand staircases and panoramic view from the rooftop balcony make the entrance fee worthwhile, even for the non-art lover.

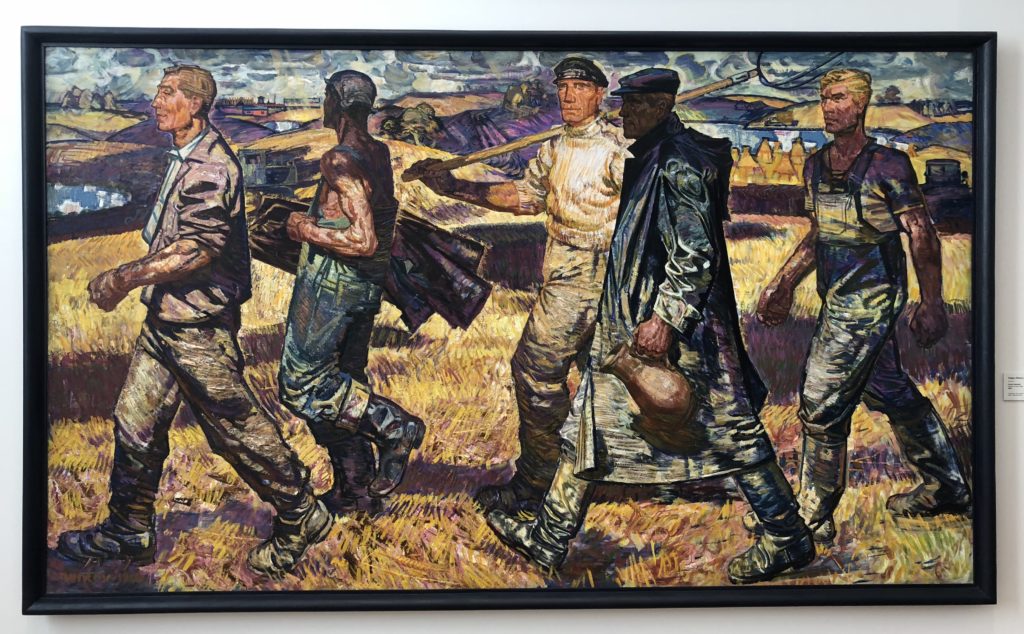

Of course, I was here for the impressive array of Latvian Soviet art, and due to the museum’s clear and easy layout, I was able to make a beeline for 1945. From the start of the second Soviet occupation until Stalin’s death in 1956, Socialist Realism was the only school of visual art allowed in Latvia. Abstract art was strictly verboten; artists were told to depict the “reality” workers and industry, all in the effort to bolster communist ideals. Of course the great irony of this form of realism was that it was nothing more than propaganda- the fakest of fake news.

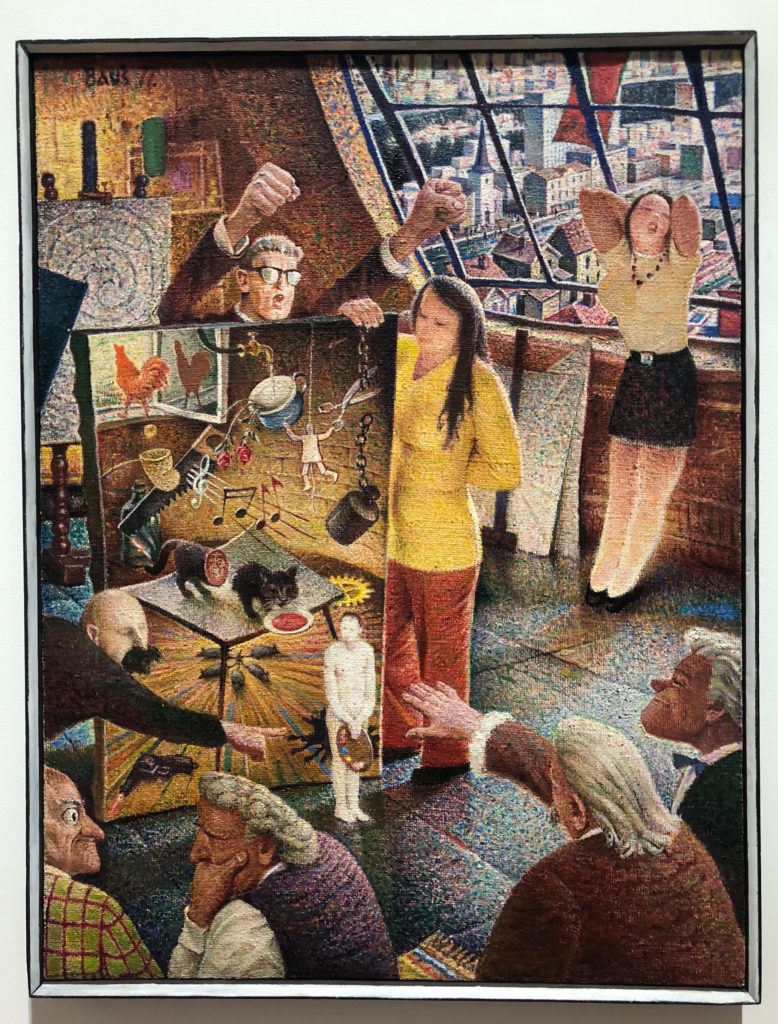

After Stalin’s death, rules and standards became more relaxed. Paintings still had to adhere to communist ideals, but abstraction was allowed to slowly creep back in. By the 1970s, the Socialist Post-Modernism movement started to see the first rebellion against toeing the party line. The creation of art itself became a major theme amongst Latvian painters of the time.

The rebellion that had begun with then Post-Modernists had exploded into a full-blown riot by the 1980s. The new, younger generation of artists came to be known as “the trespassers.” Their aim was to use the forbidden form of abstract art to depict the collapse of the Soviet Union. (Needless to say, this didn’t go over all that well with the authorities.)

After the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, Latvian artists took their newfound creative license to explore video installations and assemble found objects in order to propel Latvian art into the 21st Century.

As I mentioned earlier, one of the perks of visiting the museum is making your way to the top floor to see the sweeping views of the Rīga skyline over the tops of the leafy trees that comprise the Esplanade park behind the museum. From above one can see the golden dome of the Nativity of Christ Cathedral, the Rīga TV Tower, the Academy of Sciences Building and the Freedom Monument.

Just as interesting is a trip to the basement, where the special exhibitions are held. Like all art museums, only a fraction of the National Museum of Art’s collection is on display at any given time; the museum owns a staggering 52,000 pieces of Latvian art. During the recent remodel, glass panels replaced concrete walls that once shielded the cellar storage area from the public eye. You can now stroll through the corridors below the permanent exhibits, perusing the thousands of paintings waiting to be shuffled into rotation above.

Arsenāls

Originally built to be a Russian Customs House in 1832, today Arsenāls is a modern art museum featuring works from Latvia’s current post-Soviet existence. The old warehouse was used for weapons storage and later a military school during the Soviet era, but the Ministry of Culture eventually refitted the building into a museum when the Latvijas Nacionālais mākslas muzejs could no longer accommodate newer art.

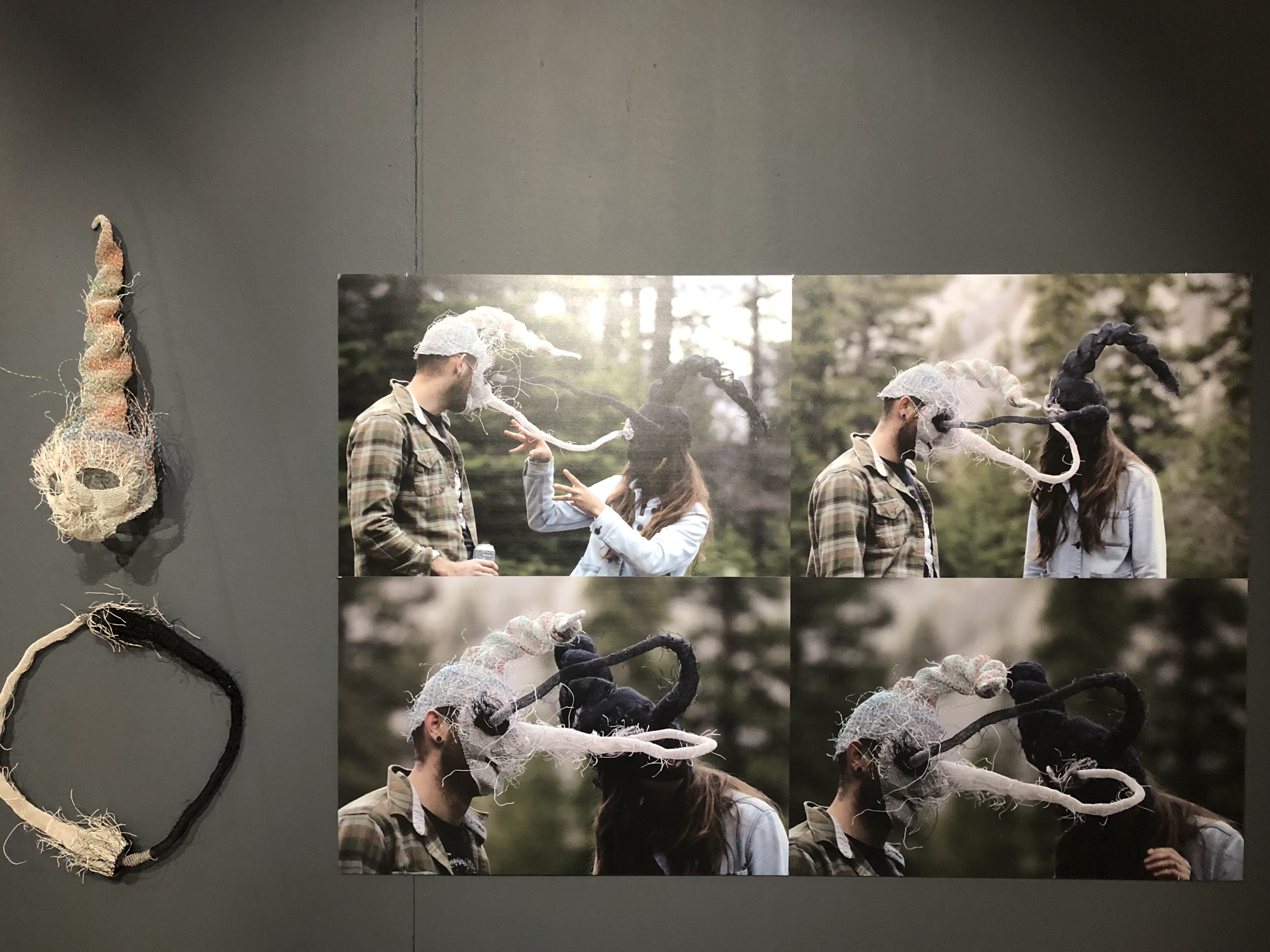

In a celebration of the 100-year anniversary of Latvia’s independence from Russia, Arsenāls assembled the exhibition “Identity” about how we view ourselves and eventually communicate our identity to the world.

Art centre Zuzeum

Rīga’s newest art museum, Zuzeum, was founded (and funded) by the Zuzāns, a wealthy Latvian family with a penchant for collecting contemporary art and sponsoring young Latvian artists. Zuzeum occupies an old cork factory built in 1910, which now falls under UNESCO’s protection. The former factory has been carefully preserved to safeguard the structure’s integrity while still creating a thoroughly modern environment to display the art.

I was lucky enough to visit Zuzeum during Riboca1 or the Rīga International Biennial of Contemporary Art. This thrilling exhibition of young artists from Latvia and the rest of the world was a highlight of my trip to the capital. Sub-titled as “BReath-TakIng, ViBrant, Offensive, CAptivating Art1,” Riboca1 dealt with the rapid changes of today, including social, political, ecological, technological and philosophical shifts in our world.

Very moving was the photography exhibit on Latvian gay and lesbian youth. Homosexuality was illegal under Soviet rule, and although Latvia decriminalized homosexuality in 1992, the nation remains one of the last EU members not to legalize gay marriage; it is illegal to discriminate against gay people in the workplace or when applying for housing. Attitudes among young people are very supportive of gay rights, but it has been difficult to stamp out the hatred instilled into the older generations by the Soviet regime. Even as gays earn more rights and protections in Latvia, they still often feel on the fringes of society. This art was meant to meditate on change, but it just may in fact help inch Latvia forward to engineer greater change of its own.

Much of the art in Rīga feels fresh and current. The focus is not on stuffy 16th-Century portrait painting, but rather it grapples with the new post-Soviet Latvia and its place in the political landscape. This new Latvia has only a few decades under its belt, and although Latvian culture is centuries old, the next generation must look forward and ask, “Who are we now?”