Independence Round One

One of the reasons I find Soviet history so fascinating is that it varies so greatly when told from different viewpoints. Estonians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Uzbeks and Tajiks (not to mention Russians) can tell wildly different tales about the events between 1917-1991 that marked the falls of both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

Having recently been in The Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia), I learned that these three nations experienced brief stints of independence between 1918-1921 before being overtaken and forced into the Soviet Union by the Red Army. Like the three nations of Caucasus, The Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) also declared their independence in 1918 as the Russian Empire was overthrown by the Bolsheviks, but unlike in their Caucasus neighbors, the armies in the Baltic were able to defend the borders and keep the Red Army at bay. 1918-20 saw the Estonian War of Independence ensure the nation’s sovereignty until 1940, when the Soviets attacked again during World War II.

KGB Vangikongid (KGB Prison Cells)

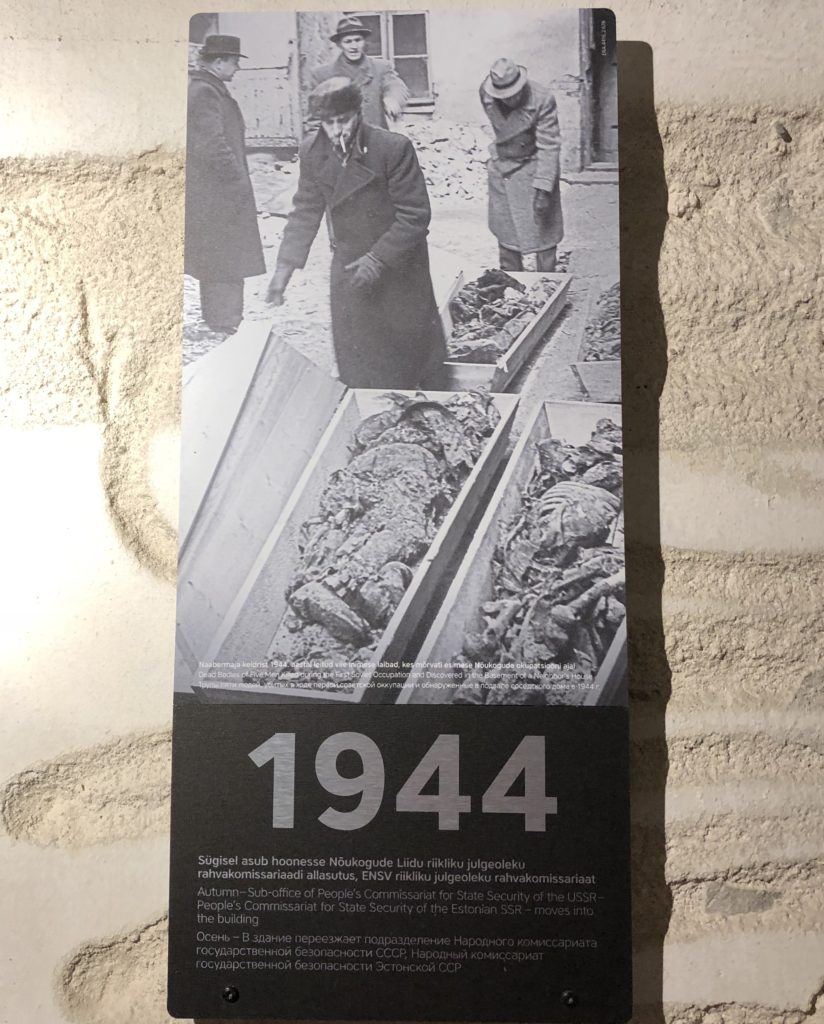

A part of the Museum of Occupation, the KGB Vangikongid have been turned into a museum and are know open to the public. When the Soviets overtook Tallinn in 1940, they were met with much resistance from the Estonian people. Between 1940-41, 10,000 Estonians were deported (mostly to Siberia) and another 8,000 were arrested, executed or sent to Soviet Gulags. Of this 8,000 arrested, only 200 survived.

If you were arrested, you were brought to these cells and ruthlessly interrogated. Prisoners were beaten, mutilated, denied food, water and sleep- they were sometimes denied the ability to sit down for up to three days. They were taken outside and forced to publicly go to the bathroom naked on the street. Doctors were kept on staff to resuscitate the prisoners when they got too close to the precipice between life and death, only for the torture to resume after they had been revived.

By the time the German Nazi Army kicked out the Soviets in 1941, the Estonian people thought at least this new set of occupiers couldn’t be any worse, but it was out of the frying pan and into fire, especially for the Jewish community. I will write more about the Nazi occupation later in this post, but after 1944 the Red Army returned and (depending on who you talk to) they liberated Estonia from the Nazis or simply re-occupied the Estonian people for the second time.

From 1944 until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, over 35,000 Estonians were imprisoned and interrogated for being seen as enemies of the state. Politicians, veterans, intellectuals, artists, writers and teachers were often rounded up without cause, but spies and informants were everyone, and the slightest criticism of the Soviet regime could see you thrown in jail and possibly sentenced to death. Estonians seen as potentially rebellious were also simply removed from their homes at night and forced to move to Siberia where they could start new lives- under complete surveillance, of course. In March 1949 alone, 20,000 Estonians were shipped off to Siberia in a mass deportation.

Patarei

Patarei was originally built as a naval fortress and army barracks for the Russian Empire in 1840. When the Estonians won their independence, the building was converted into a prison to house Soviet POWs. After the first Soviet occupation in 1940, Patarei was the destination prisoners were sent to after being interrogated in the KGB Vangikongid (if you survived the cells, your odds weren’t much better surviving the torture that awaited you at Patarei).

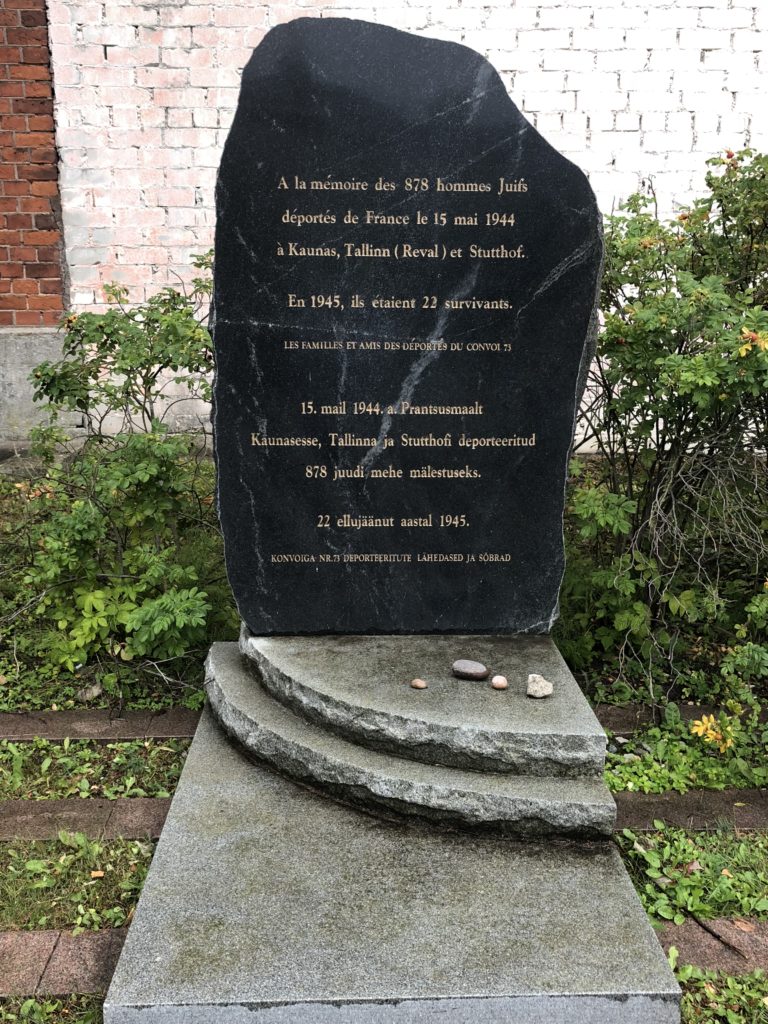

During the Nazi occupation, Patarei was used a detention center for Tallinn’s Jewish population before shipping them off to concentration camps. Occasionally the prison yard was used as a killing ground; there is a memorial for the 878 French Jews who were deported to Patarei in 1944, of which only 22 survived.

There were an estimated 4,300 Jews in Estonia before WWII, many of whom fled into the Soviet Union as the Nazis approached. Of the 1,000 who remained, only 12 survived the Estonian Holocaust and the Nazis declared Estonia “Judenfrei” (Jewish-free) by 1942. In addition, the Nazis killed over 6,000 Estonian Jewish and/or communist sympathizers during their three years of occupation.

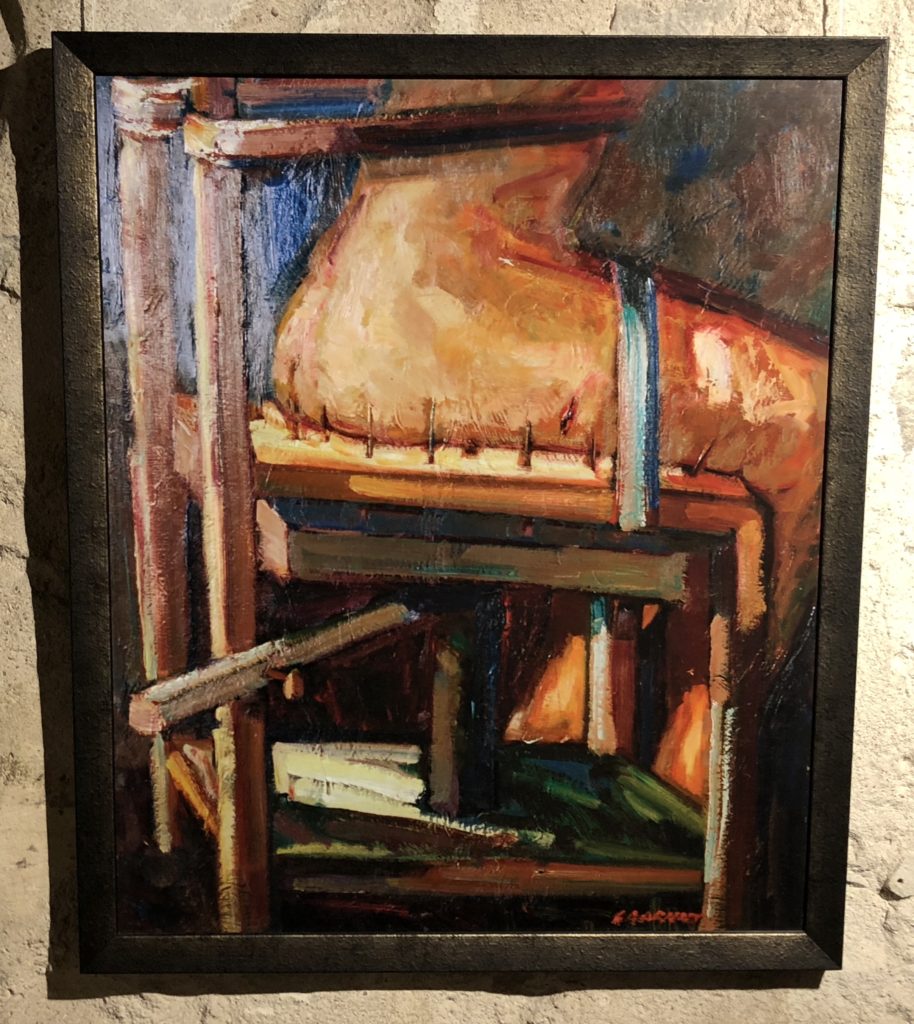

Patarei remained the most brutal prison in Estonian throughout the second Soviet occupation, with the final execution taking place in 1991 right before the Soviet Union’s collapse. The prison remained open until 2002, when the Estonian government finally closed it down and allowed artists to use the prison walls as their canvases. Tours of Patarei were given until 2016, when the building was deemed unsafe and too decrepit to walk through. When I visited, you could still walk around the outside of Patarei, but recent reports indicate that a portion of the prison has been reopened as a museum focusing on the Soviet and Nazi occupations, as well as how modern street artists have dealt with the occupations in their work.

Rahvarinde Muuseum (Museum of the Popular Front)

The Rahvarinde Muuseum may be small, but it offers the most comprehensive overview of Estonia’s fight for independence from the Soviet Union throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. Unlike the bloody struggles for independence in Latvia and Lithuania, Estonia was able to free itself from Soviet control without the loss of a single life.

In a scene more reminiscent of The Sound of Music than Saving Private Ryan, The Song of Estonia Festival helped propel Estonia towards independence in the so-called “Singing Revolution.” In an American Idol-style singing competition, Estonians rhapsodized their love for their country through patriotic songs and old folk melodies. Thousands would gather at the festival grounds over the course of four years to sing and unite the community.

On August 23, 1989, a human chain was formed from Tallinn to Vilnius, by way of Rīga, known as The Baltic Way. For one day, over two million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians joined hands, waved flags and sang patriotic songs in peaceful protest. The writing was on the wall and the Soviet Union was crumbling, but the leaders in Moscow only tightened their grip for two more years as demonstrations grew across Estonia.

On August 20, 1991, a newly elected Estonian Parliament voted to restore independence for the Republic of Estonia. The historic and emotional session was filmed and you can watch the footage at the museum, as well as newsreel of the Baltic Way and Song of Estonia Festivals. I had a lovely and moving conservation with the Estonian grandmother who was working at the museum when I visited. Having lived through these events, she told me she couldn’t believe they were actually happening at the time. She had grown up and lived through so many decades of oppression, but she told me she never doubted that one day she would see a free Estonia again. Tearing up, she said she was most grateful for the fact that her grandchildren were born in Estonia and not the Soviet Union and they would never have to experience the hardships she and her children endured.

Linnahall

Formerly known as the Lenin Palace of Culture and Sport, Linnahall was built for the 1980 Moscow Olympics; the sailing events were held in Tallinn as Moscow does not have access to appropriate waterways. The building was later converted into a concert hall, which held up to 4,200 people, but was officially closed in 2010 and has been left to rot on the Tallinn harbor. Like Patarei, one used to be able to visit the inside of the concert hall, but fear that the roof may collapse has halted all tourists from entering. (A Danish couple joined me in attempting to bribe a guard into letting us in, but luck was not on our side that day.)

Renovations are constantly being proposed, but the question remains- who will pay for them? Several people I talked to said Linnahall was an eyesore and should simply be torn down. It is a painful reminder of the past, now covered in graffiti and trash and used as a drinking/smoking hangout at night by the city’s youth. Others argued that the decaying structure should be maintained and turned into a museum. The young people who use it to party are growing up without any appreciation of the struggle the older generations went through to gain independence and Linnahall can be that teaching tool.

One can also simply appreciate Linnahall from a purely architectural standpoint as well, an exemplary model of the Soviet brutalist movement. Its current condition makes for an easy metaphor for the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union as well. While some may call this building “ugly,” I find Linnahall strangely beautiful, magnificent and compelling. Traversing it’s grounds made me feel like I was stepping over the corpse of a slain giant, awesome and scary at the same time.

Returning in the evening with a beer and watching the sunset seems to be a Tallinn rite of passage and I highly recommend it. Estonia’s Soviet history was terrifying and repressive, but the era was ended not by guns and bombs, but by singing songs. Turning buildings like the KGB Cells, Patarei and Linnahall into history and art museums is really the best use for them. The history cannot be forgotten and more importantly it must not be allowed to be repeated.